Meron Hadero was recently awarded the 2021 AKO Caine Prize for African Writing, becoming the first Ethiopian author to claim the honour. In this essay, Thulani Angoma-Mzini presents an appraisal of this year’s shortlist, showcasing as it does some of the best of the past year’s African writing.

The Caine Prize is one of African writing’s lodestars. To win, or even to be shortlisted, is generally an intimation of a noteworthy future career. Further than that, literary techniques, themes and narrative approaches often seem to echo across each crop of nominated stories, signalling perhaps an overarching genius loci or literary zeitgeist for the year.

The five stories that were shortlisted for this year’s edition of Caine Prize are all deeply affecting works. They leave the reader changed. The writers take you into the shadows that form as the sun sets on one or other relationship. You find yourself deep within the sorrow of each story, positioned right next to the protagonists in their darkest hours.

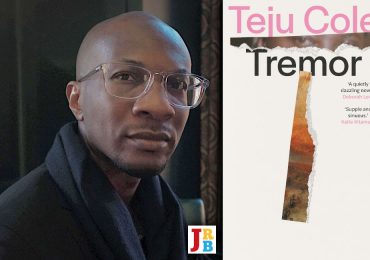

There is no doubt that the joy and utility of reading emanates from the core elements of plot and theme, but the magic of reading comes from well-written sentences. As Teju Cole says, ‘a well-shaped sentence matters’:

And my hope is that if it’s written well, it might catch somebody’s attention and be a balm for something that they’re going through, if it’s written well. And so I try to write it well.

He could have been speaking about the 2021 Caine Prize shortlisted stories. The authors are deliberate, for the most part, about where each sentence is placed and how each phrase is crafted. The result is to create portals on the page through which the reader is transported, engaging with the story either from a point of emotion or a point of intrigue.

Take, for instance, the use of the present tense in the stories ‘This Little Light Of Mine’, ‘A Separation’ and ‘Lucky’, by Troy Onyango, Iryn Tushabe and Doreen Baingana, respectively. Because events are unfolding in real time for the protagonists and the reader, both are conjoined within the tension and emotion of the stories. When Harriet, the protagonist of ‘A Separation’, is abruptly brought out of the trance of her run, the feeling is both familiar and intense:

I don’t know how long I’ve been running when a dog’s bark stops me short in a dimly lit back alley. He’s a large black dog with a rumpled coat like the skin of an elephant. A white picket fence overrun with vines separates us. He scratches at it with his paws before giving up and turning away from me.

The context of this run is important. Harriet has heard from her methodical father that her grandmother has passed on in Uganda and, as an involuntary reaction, she gets the urge to bolt out of her Canadian apartment. The present tense intensifies her jolt from half-consciousness when the dog barks: you feel what she feels; her fright at the dog, and her fear of the loss she has been introduced to by the passing of her favourite person.

That Harriet meets and almost instantly falls in love with Ganesh, whom she stumbles upon just after hearing about the end of her grandmother’s life—Ganesh, named for the elephant-headed Hindu god of beginnings—is surely no coincidence in this story about how life extends past the last breath. That her first experience with Ganesh is to drink lemongrass tea, as she did with her recently late grandmother, this second-hand reincarnation, of a kind, is perhaps an indication of a fidelity to tradition and ancestry, with a hint of global contextualisation.

In one way or another, each of the protagonists in the shortlisted stories is missing something. In ‘This Little Light Of Mine’, Onyango introduces us to Evans, a young man who has been in a debilitating car crash that has left his lower limbs limp. The first line captures succinctly how Evans has lost not only the functionality of his body but also his identity:

In the silence of the dark room he finds his voice but realises he has forgotten how to use it.

For two years Evans has been interned in a slim-wheeled wheelchair. He has lost his loves: dancing, going to the movies, a three-year love affair. What he has gained is severe loneliness and the unforgettable recollection of his fateful accident. We are introduced to the remains of a felled life filled with unwanted memories. Evans recollects a time before his paralysis, a time of careless abandon and presumptuous plans ‘to run marathons or climb Mount Kilimanjaro or do a trek along the sandy beaches of the coast’. For the most part it is these memories that torture him. Every inelegant rejection he gets from the dating app he uses (‘Sorry but I don’t do cripples’) becomes a painful reminder of the accident that now defines his life.

All the stories, in fact, present the past, memory, as the most challenging component of loss. In Baingana’s ‘Lucky’ we follow a group of boys abandoned at their boarding school at the time of the Ugandan bush wars in the mid- to late-nineteen-eighties. The narrating boy reminisces about an aging war vet back home named Okiror, who’s memories entertain the local youth but clearly haunt the old man, who looks like he is ‘made of nothing but wrinkled skin and bones’ and who sits under a tree ‘holding an ancient gun like a baby’. Okiror has lost everything to the conflict. While the youngsters are enthralled by how he rattles off the names of military issue artillery (‘Beretta 92, AK-47, AKM, AK-74, Type 56; what hadn’t I learnt from Mzee Okiror?’ gloats the young narrator), it is clear by how mixed up his recollections are that the man’s brain is mangled by Post Traumatic Stress Disorder:

It seems he had fought in every army: one day he would say he was with the African Rifles of World War II, fighting for the British in Burma […] then next the colonial army had to ‘pacify’ the Karamajong […] Then the next time he said he took part in the attack on the Buganda King’s Palace in Kampala in 1966; then later he volunteered with the SPLA in Sudan in the 1980s; and even later trained the UNLA to fight the NRA.

Memories carry grief, too, for the protagonist of Rémy Ngamije’s ‘The Giver of Nicknames’, who recalls a time when he wielded a wit of great renown, the ‘much sought after merchant of humiliating sobriquets, the fast-mouthed comeback kid who could roast the devil over his own coals’. With lucidity and just a hint of remorse the narrator reflects on the consequences of actions that, as a child, seemed innocent enough, and his role in both defence and offence in the games that teenagers play. While the loss for this man is not direct—the death of a schoolmate—it seems, as is the case with the protagonists of the other stories, to be the thing that concentrates his mind towards some or other resolve.

And with regards to resolution, while all this year’s stories begin with loss, it is hope that energises the final movements of each. In Meron Hadero’s ‘The Street Sweep’, Getu, a young Ethiopian street sweeper, is befriended by an American NGO worker, Jefferson Johnson, who expropriates from him ideas for simple, effective socioeconomic solutions to the problems the local people face, in exchange for platitudes like ‘we could use a man like you’, which Getu takes literally. When Jeff invites Getu to his farewell party at an incongruously opulent hotel, the sweeper thinks this will be his opportunity to obtain the job that will bring life to his dreams. The hotel itself presents as the juxtaposition between Getu’s world and that promised by Jeff, with a nightclub appropriately named ‘the Gaslight’:

The Sheraton created a sense of hope when it opened its arms to the few, and so occupied the ambitions of many. [It] was a strange presence in this impoverished city, an isle of exclusive luxury that didn’t quite touch down.

When Getu shoots his shot and asks Jeff for a job outright, the American recoils:

‘Getu, I’m afraid you’ve somehow been misinformed,’ said Jeff Johnson, avoiding Getu’s eyes.

‘But didn’t you say you had something for me? And what else could it be, all this talk of working together?’

‘Did I say that? Yes, I guess I was just, not being literal,’ and Jeff Johnson furrowed his brow and started to walk quickly toward the gate. Getu walked sort of next to him, sort of behind him trying to keep up.

The timid Getu, who throughout the story has sensibly attempted to curb his own enthusiasm at the potential life-transforming job with the big American NGO, should be decimated by this change in step. But he is not. Understanding, now, the currency of figurative language over literal, he uses the opportunity of Jeff’s farewell to his own benefit. Taking advantage of ‘a door still left a little ajar’, he re-enters the party, impersonating a WHO interpreter with confidence. The story is closed on the promising note of ‘tall glass doors’ being ‘flung open’.

In this year’s Caine Prize shortlist, we are delivered to a new, contemporary age of writing. The authors are paddling through the persistent pain and suffering that flows over the African continent from south to north, like the Nile river, but they are doing it with a style and ease that belies the challenges faced. Read these stories, which explore the recesses of loss with uncommon elegance, and see if you don’t find a set of doors being opened, too.

- Thulani Angoma-Mzini is a South African aspiring creative non-fiction writer with a passion for reading and a desire to write more.