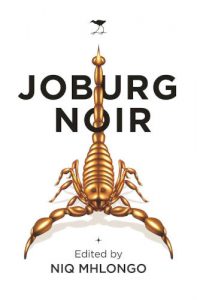

The JRB presents an excerpt from Joburg Noir, a new collection of short stories edited by Niq Mhlongo, out at the end of October 2020 from Jacana Media.

Joburg Noir

Edited by Niq Mhlongo

Jacana Media, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Feasting

By Sibongile Fisher

I met my lover on the night the city caved in and feasted on the hearts of three young women. The following morning, newspaper headlines spilt out of everyone’s lips. The radio broadcasted a different version of events to the one told by the woman in the taxi. Hers was more elaborate, detailing the exact positions the women had been found. One was in a trash can and another on a church doorstep. The third had been casually discarded on the side of the road. ‘Satanism!’ another woman proclaimed, and that’s how the sermon began and prayer unfolded in a red ‘Zola Budd’ on Albertina Sisulu Road.

I got off on Commissioner Street and met with my colleague at Carlton Centre. Together we snaked past Marshalltown and into Newtown, to the new mall where we both worked. We were met by alarmed co-workers; animated in discussion over yet another version of the same events. In this retelling, the three women were all friends and lived together. They had just moved to Joburg and were walking home after a long day of job hunting. A crime that was fit for a cult.

‘What if we are next?’ my colleague asked, while worry twisted her forehead.

Disappointed by my nonchalant remarks, she resumed chatting with the others. What they all didn’t know is that I am from a small mining town that for many years was plagued by the mountain men. It all began when the mines closed, and the workers were left to rot in the violence of their impoverished demise. What had happened to the three women was no new headline to me.

In our small mining town, they—the mountain men—sift the sands in the eastern parts for diamonds and dig in the large old mining hills for any gold or gold remains. Here, they dig deep beneath the City of Gold for their lost fathers, uncles and brothers who never made it back home. In the hole they are most alive, bending their backs to marry their childhoods with the dusty rocks of what haunts them. The alchemy of their pride. Searching for the ghostly remains of the riches that were meant to raise them. They slither in and out of the old mines belted around the city. Some of them live underground and most of them live in informal settlements on the outskirts of the basin. This is their legacy. And it is mine.

Johannesburg swallowed my father whole. His body was never found. We held a funeral for a picture and his favourite clothing items. His death left us poor and adrift, and after that, my mother hated this city. The tall buildings that cast shadows too soon. The shy sun that hides behind them. The potluck of people constantly on the move. The heavy silence of danger stalking you.

To her, the city was an open grave that buried anyone who fell in love with it. Her resentment was rooted more in his absence when he was still alive than in his death. She never spoke about it, but the fact that he had another family in Joburg ate at her insides until she met her death two years after. But, for me, Joburg is where the ghost of my father roams. It is here I feel closest to him. His body has fertilised the ground these buildings stand on. The despair of my childhood is married with hope here.

It took a while for the headlines to die down. I, on the other hand, had grown fond of my new lover—an unmarried one. When I first moved to Joburg, my mother cursed me never to get married. She had hoped that loneliness would lead me back home. Over the years, I’d met many lovers, most of them married, and in need of some time out from their wives, so nothing serious came of it. And besides, I knew that my mother’s curse was going to live on. But this new lover—who appeared after I had sworn off men—was marked with the strangeness of chance. He was unmarried and from my hometown, but we had never met until the night of the first attack. Our meeting was an orchestrated band of misfortunes. We were forced to start a conversation on the side of the road after someone who had not paid in the taxi, had decided to keep mum. I then left my phone on the seat beside him, after getting into another taxi, and I arrived late for work and received my final warning. I was then sent home to await my hearing. He had to ask one of the cellphone shop owners to hack my password. The first person he called was my colleague who felt it safe to share my home address. That night I received a knock on my door that has had me spinning since.

The second attack happened shortly after the headlines were arrested by a sex scandal between a minister of Lord-knows-what and a popular TV star. This time, it was an eighteen-year-old girl from Hillbrow. She was walking home alone after being chased out by her friend for refusing to sleep with her brother. She was found on a platform at Doornfontein train station. The third attack happened three weeks later. This time, it was a sex worker. The city looked the other way. I only knew of this attack because my lover had told me about it. Thereafter the attacks became common.

The mountain men had one rule: You did not harm children who had not yet hit puberty or the elderly; everyone else was fair game.

At work, my colleague fizzled under my tempered tongue.

‘Why are you not bothered by these murders? What is wrong with you?’

‘Nothing.’

‘You are waiting for someone you love to be killed by these Satanists before you can care!’

‘No.’

I wanted to tell her about Leano, but in the end all I did was grind my teeth. I moved to the storeroom and left my colleague to gossip about me with the others. The less they knew about me, the better, I thought. Besides, I hadn’t come there to make friends.

Leano and I were friends for as long as our palms had grown to clasp one another. Ours was a friendship born of fate. Our mothers were best friends, and so were their mothers. In our final year of school, the mountain men raided our classrooms. They saw us as young adults with blood ripe enough to strengthen them. Leano and I had slipped through the mayhem and made our way across the main road, down a slender passage and into Ntate Nhlole’s house. That is how we escaped the narrow hand of death.

Our useless municipal councillor did nothing after that raid. And the police only acted when the mountain men had mistakenly kidnapped those closest to them. Fear presided over our lives that summer, forcing us to stay locked indoors. But still, two summers later, Leano died at the hands of Theko, her high school sweetheart.

My lover and I had been dating for four months while the city slipped into a recurring pattern of news. A week on the mountain men and their latest victims was followed by another week of sex scandals and corruption. Then two weeks of headlines no one really cared about. One story that remained throughout: lingering like background noise, was the story of the businessman’s daughter. Her death caused the country to spiral into a rage of protests, held in solidarity with the city and the businessman’s family. The police rampaged across the city arresting any man with ‘miner’s hands’—only to release them due to ‘lack of evidence.’

The people in my hometown gained some notoriety by sharing what they knew about the mountain men. They—the mountain men—were willing to kill your enemy for you for as little as R300. All they asked in return was to eat the heart of the victim and for you to bury the liver at your gate. The heart is to protect them from the rage of the earth, and the buried liver is how they win cases brought up against them on the rare occasion the police do their work.

The main suspect was the businessman’s long-standing rival. The police released him after they had found nothing when they dug the ground outside his gate.

What the people in my hometown neglected to mention was that ‘home’ is where your umbilical cord is buried. And so, if they truly wanted to know whether the man was innocent or not, they should have travelled to the home where he was born and raised. He apparently had motive and what better way to disguise a murder than under the trending murders of a cult?

While bodies piled up all over the city, my colleagues continued to ramble on about how they feared falling prey to the mountain men. And unlike the businessman’s daughter, for them, justice would entail a headline in a community newspaper that would end up in someone’s toilet after a week.

Winter edged closer. A cold wind swept through the city. The change of season moved the burden of fear from my chest and into my lover’s.

The mountain men eat women’s hearts only in the summer. It is harder to dig in winter than it is in summer, and a man’s heart shields him from the harsh winter winds. A man’s heart also hardens him. It is harder to kill in winter than it is in summer. The night slips in earlier in the winter, shortening their time in the hole. The ground hardens, making it tough to sift. Nonetheless, it is easier to feast on a woman than it is on a man. Which goes without saying that there is more feasting in the summer than there is in the winter.

~~~

- Sibongile Fisher is a writer based in South Africa. Her short story ‘A Door Ajar’ won the 2016 Short Story Day Africa Prize, and was shortlisted for the 2017 Brittle Paper Literary Prize and the 2018 Nommo Awards. She won the 2018 Brittle Paper Literary Award for Creative Non-fiction for her essay ‘The Miseducation of Gratitude’ published by Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction. Her publication credits include: Migrations: New Short Fiction from Africa; Between the Pillar and the Post, Diartkonageng; Selves, Afro Anthology; Prufrock Magazine; Mail & Guardian; and Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu.

~~~

About the book

Joburg Noir is a collection of writings about memories, legends, loss, jokes, stories, myths and experiences by twenty-two gifted and versatile authors in South Africa.

It makes the reader experience present-day Johannesburg as if one were in the past.

The stories seek to understand, reconstruct, reinvent and recover this city space of loss, joy, deprivation, resistance and possibility by revealing its complex dynamics. They are funny, shocking, violent, absurd, strangely tender and memorable.

Their lasting resonance lies in the fact that they invoke the joys and traumas of the past and present, making the two to co-exist and interlock.

After reading this uncompromising and gritty anthology, the reader is bound to feel like a time-traveller who has voyaged into a magical alternate city and a reality that was either misnamed or not named at all.

The intention is to help the readers to delve into their own memories in search of pictures of their sweet childhood and fractured identities.

Contributors: Sam Mathe, Fred Khumalo, Lidudumalingani, Keletso Mopai, Sibongile Fisher, Styles Lucas Ledwaba, Mapule Mohulatsi, Khanyi Magubane, Sifiso Mzobe, Gloria Bosman, Nedine Moonsamy, Yewande Omotoso, Mabel Mnensa, Nthikeng Mohlele, Siphiwo Mahala, Nkateko Masinga, Mzuvukile Maqetuka, Sydney Mojoko, Michelle van Heerden.