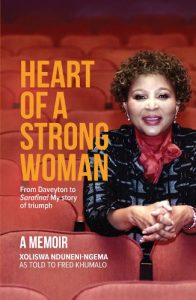

The JRB presents an excerpt from Heart of a Strong Woman: A Memoir by Xoliswa Nduneni-Ngema, as told to Fred Khumalo.

Heart of a Strong Woman: A Memoir

Xoliswa Nduneni-Ngema and Fred Khumalo

Kwela, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Chapter 4: Higher learning

When we finally got back to Johannesburg, Mbongeni moved very fast to live up to his promise that he would marry me.

‘You have seen my people,’ he said, ‘they have accepted you. My mother, as you know, likes you very much. That was why she was sharing all those words of advice with you. She likes you, she wants you to be her makoti.’

To that day, I was still happy that on the issue of polygamy, he had put his foot down. I was saddened that he had to defy the old man who loved him so much, but I realised that inasmuch as he loved and respected his grandfather, he had my interests at heart. He had our future at heart.

To reassure me that he was still committed to making me his wife, Mbongeni quickly fulfilled his ilobolo obligations. That done, we were ready to walk down the aisle. However, because of our financial situation—I was fresh from high school and still unemployed, and we didn’t have a place of our own—and the fact that he was busy with Woza Albert!, it was decided that we would do the proper, full-blown white wedding later. For now, to make our union legal as husband and wife, it was decided we would go to a marriage officer at the local magistrate’s court. Unbeknown to me, Mbongeni had invited a team from the Sowetan newspaper—a reporter and photographer—to come and immortalise the moment. A few moments after signing the necessary documents, we stepped outside the government building to be greeted by the men from the paper.

Brimming with new-found joy, we posed for the picture. Mbongeni was dressed in a tracksuit, and I in an Indian-style outfit. The day we signed our names to eternal matrimony was 22 February 1982. I was nineteen years old, what a way to start the year.

The previous year, 1981, before we were married, had been hectic for both of us. Mbongeni had been on the road most of the time. Woza Albert! had truly taken the country by storm. They travelled to Cape Town and Durban, spending long stretches of time in each city, performing to full houses. I was happy for him. So happy and besotted that I even became careless. For the first time in my life, I spent a night away from my parents’ house. I spent the night at the house Mbongeni was sharing at the time with Percy Mtwa out in Pimville. When I went home, my mother beat me to hell and back. Using a belt and then a huge switch from a tree that stood in our yard, she attacked me as if I was an enemy, not a child. In the township, girls my age – I was eighteen at the time—often slept over at their boyfriends’ houses. It was no big deal. But at the Nduneni home, things were different. My parents were pretty open-minded, but when it came to a girl ‘sleeping out’, to use the township argot, it was a no-no.

The disciplinarian at home was always my mother. My father would give you some stern words, but when it came to the physical part of the punishment, he would sit back and my mother would take over from there. She was hot-tempered, living up to the stereotype that coloured people were loud and violent.

Another blight from the year 1981 was when I walked in on Mbongeni in bed with another woman. I had gone to the house in Pimville unannounced. Naturally, I blamed myself. I should have warned him that I was coming to visit. That was how it was done. A girl who went to her boyfriend’s place without warning was only asking for it. That’s what I was later told by other girls. You simply did not pitch up unannounced. Growing up in a township, one got to accept that a real man couldn’t have just one girlfriend. No ways. He could have one ‘steady’, and then numerous ‘roll-ons’, as secret lovers were called. Like a roll-on deodorant you use in your armpit, a secret lover was kept underneath, in your armpit. Roll-on. Or umakhwapheni. Even married men had umakhwapheni. It was the norm. Personally, I knew I could never be comfortable with this crazy ‘norm’. I could never share a man. It truly hurt me that this man whom I loved, respected and treasured so much still wanted to share me with another woman. The disappointment was made acute by the fact that he had already introduced me to his people. He had defied his grandfather when he vowed never to entertain the idea of polygamy.

When we finally got married in February 1982, I dismissed my fears and reprimanded myself. You’re being too harsh on him. He was just having his last fling before getting married, before committing himself to you. It was good to see that picture of us in the Sowetan. The reporter who interviewed Mbongeni that day seemed to hold him in awe. Even back then when he was still really small fry, Mbongeni knew how to ingratiate himself with people who mattered. In years to come he would have lots of influential people—in the media, the government, the financial sector, the music industry and so on—at his beck and call. He’s always been a people person. When he turns his charm on it is difficult to turn him down.

Back in Daveyton, everybody congratulated me on making the pages of the Sowetan. Little did I realise that appearing in newspapers, being fêted at top hotels and restaurants, and having the red carpet rolled out at my feet would become second nature to me in a few short years.

As Mbongeni had told me before he took me to his folks in rural Zululand, the day finally came for Woza Albert! to go overseas. This was to be Mbongeni’s first international flight overseas. Although he was on cloud nine about the achievement, he was very calm about it. That’s the thing with him. He wears success quite comfortably, as if he was born with it.

Born in Verulam on 1 June 1955, Mbongeni was the third of seven children of Gladys Hadebe and Zwelikhethabantu Ngema, a policeman who himself had been born in the village of eNhlwathi, in kwaHlabisa, outside Mtubatuba. The town of Verulam, where Mbongeni was born, was where his father was stationed. It was predominantly an Indian area in terms of population, but there were a sizeable number of black African residents in the town. With the advent of the Group Areas Act of 1950, which decreed that whites, Indians, coloureds and blacks outside the tribal reserves were to live in circumscribed communities among their own kind, Verulam was reclassified for exclusive Indian occupation. As a result, black Africans who lived there had to be relocated to ‘where they belonged’.

Although Zwelikhethabantu Ngema could keep his job at the local police station, he had to vacate his house. He and his wife found convenient lodgings nearby, but the children were sent off to kwaHlabisa. This was a dramatic development for children who had grown up in a place with such modern conveniences as running water and shops within close proximity.

At kwaHlabisa, where the Ngema children were to live with their grandfather Vukayibambe, they had to learn a new way of life. Each morning, Mbongeni and his brothers rose with other children at around three o’clock to harness a span of oxen. They would then drive the animals down to till the fields by the light of a lamp. By six o’clock, Mbongeni would walk back home—it took him around 45 minutes—where he would bathe, dress in his school uniform, tuck into a bowl of amasi and walk to school. At around three in the afternoon, when school let out, he’d run back home to help his grandfather with the oxen again.

Mbongeni remained on the farm until he finished Standard Six. Then he was sent away, back to Verulam to stay with one family and later with his elder brother Johannes, and continue his schooling. From there he drifted about numerous townships in the Greater Durban area, staying with relatives and friends. In Umlazi, he stayed with the Gumedes, and started attending Vukuzakhe High School.

He dropped out of his final year of schooling and started playing with music bands in townships such as Clermont and KwaMashu. In between performances, he took on numerous jobs to keep himself financially afloat. Like all restless souls, he finally succumbed to the lure of Johannesburg, the City of Gold, where he joined Gibson Kente as a singer and trainee actor.

By all accounts, when Mbongeni arrived in the United Kingdom for the first performances of Woza Albert!, he did not appear to be overwhelmed by the sheer size of the place, the sheer modernity. He took things in his stride and got on with his job. Woza Albert! won Edinburgh’s Fringe First Award after the play was shown at the famous Edinburgh Festival. When, a few months later, the play went to London, Mbongeni flew me to the famous city. It was an overwhelming experience. First, the flight itself was something else. Barely nineteen years of age, and being black, I was flying on an aeroplane. You laugh. Back then it was no laughing matter for a black South African to fly on an aeroplane. Even if the person in question was flying from Johannesburg to Durban, it became a talking point in the neighbourhood. On the day the person was to fly, those relatives and neighbours who had cars would get dressed in their Sunday best, load members of their family into the car, and drive ceremoniously to the airport. At the airport, the party to see the traveller off would start singing and ululating, congratulating the traveller on his or her achievement.

So here I was in London, having travelled all those hours from South Africa. My husband had just wowed audiences with his energetic performance. Now we were at a private party in Hammersmith. The partygoers smelled of sophistication and wealth and the place buzzed with energy and positive vibes, dripping with gaiety and joie de vivre. Lots of hugging and kissing and flirting. Uproarious laughter. My head was swimming. All these faces of rich-looking people, black and white. I’d read a lot of reviews of the play in the British press, all of them full of praise. Now I witnessed the excitement myself—the partygoers were even more gushing with their praise. The more I listened to people’s comments, the more I realised just how powerful Woza Albert! was, how it had become the perfect vehicle for putting the story of apartheid in the public domain so the whole wide world could see what South Africa was truly like under the racist oligarchy.

~~~

About this book

Xoliswa Nduneni-Ngema loved the theatre and dreamed of being an actress. She soon discovered that acting wasn’t for her—managing productions was. She meets rising star Mbongeni Ngema and they marry.

As his success grows, they start a company that births the hit Sarafina! But beneath the stardom, Xoliswa experiences constant abuse.

With Fred Khumalo, she tells her powerful story.