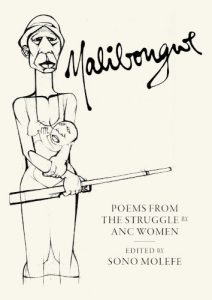

The JRB presents an excerpt from Malibongwe: Poems from the Struggle by ANC Women—a new edition of a lost piece of South African literature.

The book was originally published throughout Europe during the nineteen-eighties, but was banned in South Africa by the apartheid regime. This is the first South African edition of Malibongwe, a book four decades in the making, which re-establishes a place for women poets in exile in the artistic history of the Struggle.

The legendary artist Dumile Feni contributed a number of illustrations to the second German edition of Malibongwe, but these works were until recently unknown to Feni scholars, and even his own family. The book’s publisher uHlanga Press managed to recover copies of the images to add to the archive of known Feni works, and the artist’s estate granted permission for one of the images to be printed on this edition’s cover (see below).

The book was made possible by ‘Recovering Subterranean Archives’, a project that seeks to repatriate and republish South African culture from exile, headed by Uhuru Phalafala of Stellenbosch University, and funded by Andrew Mellon.

Scroll down to read a selection of poetry by Lindiwe Mabuza—who under the nom de guerre Sono Molefe championed the Malibongwe book project—Baleka Kgositsile (now Baleka Mbete) and Lerato Kumalo (the pseudonym of S’bongile Mvubelo).

Malibongwe: Poems from the Struggle by ANC Women

Edited by Sono Molefe

uHlanga Press, 2020

Read an excerpt from the Introduction, written by academic, poet and JRB Patron Makhosazana Xaba:

‘What does it mean to giggle at the wrinkled hands that pried open bolted doors so we could walk in and take a seat at the table?’ Grace A Musila, a literary scholar with interests in (among others) gender studies, the African intellectual archive, and postcolonial whiteness, raised the above question in a recent article about the contribution made by postcolonial theorists—those who ‘fought the epistemic injustice of canonising certain literature over others’—to our current times. Grace’s question is pertinent and timely, and shouldn’t be limited to being asked of postcolonial theorists. The South African edition of Malibongwe—compiled and edited by Sono Molefe, a.k.a. Lindiwe Mabuza—excavates the names of poets whose wrinkled hands contemporary Black women poets need to know about and then acknowledge whichever way they see fit. Some might want to shake their hands in gratitude. Others might wish to hold hands, just as a way to connect. Some might want to buy some moisturising hand cream and offer it. Hopefully none will giggle.

Giggling at the poets and poetry borne of what the foreword to the original edition called ‘a love deeply rooted in their usurped land’ would constitute a failure to recognise their significance. To return to Grace:

One thing Black women artists have taught us is the importance of acknowledging our intellectual histories and those who dreamt the futures we enjoy, and our responsibility to dream more liveable futures for those behind us.

While living in exile I knew about the existence of Malibongwe, but I never held a copy in my hands. It was only in the late nineteen-eighties that I met Lindiwe, as well as three of the book’s contributors, Baleka Kgositsile, Ilva Mackay and Rebecca Matlou. While I lived in Lusaka, Zambia, I shared a communal African National Congress (ANC) home in Chilenje with Rebecca, while Baleka lived close by, no more than a ten minute walk away. Eventually I learned that the two of them were poets. Later, I learned that Lindiwe and Ilva were also poets. I never came across their work while in exile. What I do know is that these poets—or these hands, to return to Musila’s metaphor—pried open bolted doors so I could walk in and claim a chair around the literary table, even though I never wrote a single poem while living and moving within the ANC spaces and places in exile. These poets’ multiple identities as comrades spanned from being activists to ambassadors (Chief Representatives as we called them, pre-nineteen-ninety), as well as combatants, feminists, guerrillas, mothers, public intellectuals, scholars, sisters, wives, writers, and more. For this anthology, I wish to call them comrades-cum-poets. These poets are, for me, living examples of the ever-expanding range of identities we can claim, as women. Although I have loved and enjoyed poetry all my life, it was only in 2000 that I began to claim it and write. It became an easy transition because in my earlier life I had known Black women who were poets. To finally place my hands on the Malibongwe manuscript makes me want to say: Malibongwe indeed!

Read a selection of poetry from Malibongwe:

~~~

Soweto road

Lindiwe Mabuza

On this spot rough

from cares of slow years

on these streets

muddy from torrents red

on these crooked roads

yawning for direction

here where like early spring

awaiting rain’s seeds

young voices stormed horizons

how yet like summer streams

young blood flowed over

flooded flower

in the dead of winter

On this road here

here this road here

tingles and shudders

from acid taste

the snakeskin snakestooth whiplash road where snakes tongue flicker lick

broken glass children’s park

road school for shoeless feet …

olympic track perfected

by daily daring sprints

against passes

and barbed wire nakedness …

this road pressed soft

oozing like tear-falls

treeless showground for hardware processions

all the June sixteen festivals

and their mad array of hippos

muffling contrary anthems

with machine-gun chatter

naked greed and lust for blood in camouflage

Soweto road drunk

from rich red wine

this sweet arterial blood

for choice Aryan folk …

battlefield road here yes

Here

yes even here

where road-blocks to life pile

precariously

here we kneel

scoop earth raise mounds of hope

we oath

with our lives

we shall immortalise

each footprint left each grain of soil that flesh shed here

each little globe of blood

dropped in our struggle

upon the zigzag path of revolution …

Soweto blood red road

will not dry up

until the fields of revolution

fully mellow tilled

always to bloom again

~~~

Exile blues

Baleka Kgositsile

let them roll

let the blues roll out

but ‘this load is heavy it requires men’

has nothing to do with baritone or beard

it is a word of warning wisdom

when the uncontrollable miles

between you and home

the beautiful land

you vowed to liberate

become unbearable

and you ask yourself

if it was worth your leaving the loved ones

as if you left home

a victim of a stupor

when having been rejected

like vomit from a stomach

you try to examine

if it is the food that is stale

or the stomach that is sick

when you are threatened by paralysis

in the midst of so much to be done

when the pettiness has played so many games with you

that like an addict

you do not remember when you did not crave

just another piece of gossip

when the demon trinity

inferiority complex

self assertion

sadism

have become your masters

that you put the stamp

on your own death certificate

as you try to destroy

when you drink yourself insensible

into the gaping dark void

that is ready like the vicious jaws

of a shark to receive you

when some other comrades have fallen victim

to mental breakdown

and you shudder wondering

if you won’t be next to be ambushed

when you make a habit of exchanging blows

that should be kept for the enemy

when you feel trapped

suffocating cornered

at a cul-de-sac

and your tears roll down uncontrollably

as memories invade you daily

maybe let them roll

let them blues roll out

let them roll out the blues

till oblivion sneaks to your rescue

when later you feel lighter

retrieve the zeal that made you leave home

lest you go down the drain

with the stinking rot of history

when the song goes

‘this load is heavy it requires men’

that has nothing to do with baritone or beard

it is a word of wisdom and warning

that our history is so reddened

with the blood of the best of our land

even the enemy gets more vicious by the second

because the enemy also knows

‘victory is certain!’

is not an empty slogan

~~~

No more words now

Lerato Kumalo

I get your point precise

lady, gentleman of the world

you say you know

apartheid is a crime against

humanity

and you are part of it

I realise your argument

that it is certainly indefensible

to give approximately 87% of our country

to about 13% of the population

that originally came from

where

you unfortunately are part of

I read but scorn your logic though

that violence begets violence

when you supply guns and money

to those who had them, have had them and have them,

that two wrongs don’t make a right

when countless times

you veto my freedom

at the United Nations

that diplomacy works wonders

when you fatten on the blood of my people

in that part of the

world

you unfortunately are part of

But my point argument and logic

come

from piles of dead bodies

and the necks struggling under the yoke

ask them what they think of me

‘a nice girl like you’ as you put it

when I shoulder with pride

this AK-47

ask what they think of you

and your cocktail party wisdom

‘a nice person like you’

No more words now

till our Nuremberg trials

judge the rallies

and weigh Munich

~~~

About the book

you say you know

apartheid is a crime against

humanity

and you are part of it

The first South African edition of a Struggle classic.

With a new preface by Uhuru Phalafala and a new introduction by Makhosazana Xaba, and featuring a lost artwork by Dumile Feni.

In the late nineteen-seventies, Lindiwe Mabuza, a.k.a. Sono Molefe, sent out a call for poems written by women in ANC camps and offices throughout Africa and the world. The book that resulted, published and distributed in Europe in the early nineteen-eighties, was banned by the apartheid regime. Half-forgotten, it has never appeared in a South African edition—until now.

Authorised by the editor, this re-issue of Malibongwe re-establishes a place for women artists in the history of South Africa’s liberation. These are the struggles within the Struggle: a book that records the hopes and fears, the drives and disappointments, and the motivation and resilience of women at the front lines of the battle against apartheid. Here we see the evidence, too often airbrushed out of the narratives of national liberation, of a deep and unrelenting radicalism within women; of a dream of a South Africa in which not only freedom reigned, but justice too.