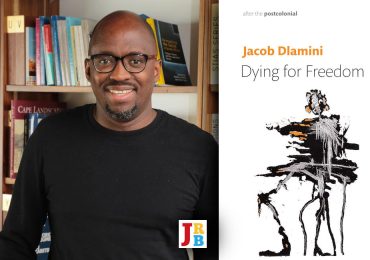

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from The Terrorist Album: Apartheid’s Insurgents, Collaborators, and the Security Police by Jacob Dlamini.

By using a small object to tell a big story about South Africa between 1960 and 1994, I intend to cut apartheid down to analytical, moral, and political size, thereby challenging the myths that continue to surround popular understandings of apartheid. As the dream of a democratic and egalitarian South Africa disappears into a twenty-first-century hellhole of corruption and increasing economic inequality, apologists for apartheid have taken to saying something along these lines: ‘The apartheid state might have been authoritarian and brutal but at least it was efficient’; or ‘Blacks were better off under apartheid’; or ‘the apartheid police were murderous bastards but they at least knew what they were doing.’ Such revisionist claims are similar to the arguments made in defense of Italian fascist Benito Mussolini, under whose dictatorship the trains supposedly ran on time. We give the apartheid state too much credit, however, by assuming that it was efficient. It was not. This did not make it less brutal. But efficient it was not. It could not always tell its friends from its enemies, its Indians from its whites. We only have to look at the album, feel its pages, and listen to its voices to know that.

The Terrorist Album: Apartheid’s Insurgents, Collaborators, and the Security Police

Jacob Dlamini

Harvard University Press, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Who are you who will read these words and study these photographs, and through what cause, by what chance, and for what purpose, and by what right do you qualify to, and what will you do about it?

—James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

If I open my old photo albums, my companions from the past, most of them dead now, look back at me. Some days it gives a sad kind of pleasure, and then other days, the same activity brings me face to face with nothingness. So many of the men, the women, were young and charming, truly beautiful. They will never be old. Soon it becomes intolerable to realize that they’re in a tomb or reduced to ashes. I close the album. When I look at those photos from the past, I have the impression that the present is a foreign country. I live here in exile.

—Roger Grenier, A Box of Photographs

Prologue

In October 2018, I met two former members of the South African Security Police to ask for their help in solving a number of archival puzzles. I was working with files, remnants of the apartheid security archive, and wanted to know, among other things, why the police gave their agents, informers, and sources in the anti-apartheid movement codes that began with the prefixes HK, RS, and OTV. What exactly was the difference between agent HK 619 and agent RS 195—both of whom seemed to be spying on the same meetings of the exiled African National Congress (ANC) and whose reports were synthesized into one report? Was it a difference in kind? If so, what and how?

My helpers, a lieutenant-general and a brigadier (both long retired from the South African police), were veterans of the Security Police, having joined in 1963 and 1964, respectively. Each had participated in every major Security Police mission, from the smashing of domestic opposition to apartheid in the 1960s, to South Africa’s paramilitary misadventure in Rhodesia in the late sixties, and to the repression of extraparliamentary political activity in the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s.

Each had risen through the ranks of the Security Police at the height of the fight against what the South African government called terrorism.

I had known the brigadier, a fellow historian and the unofficial chronicler of the apartheid police, for some four years at this point. A shared interest in the history of policing and politics in South Africa had brought us together. As so often happened in my meetings with former members of the Security Police, discussion soon turned to the destruction of South Africa’s security archive shortly before the formal end of apartheid in 1994. That memory purge was so extensive that some commentators have called it a ‘paper Auschwitz’.

Why, I asked the two men, had the Security Police destroyed their records? The brigadier’s answer caught me by surprise. ‘The greatest form of terrorism,’ he said, ‘was to destroy our documents.’ Coming from a man who had dedicated his professional life to fighting terrorism, this was strong stuff indeed. Warming to his theme, the brigadier relayed an argument that he had recently had with the general who was in charge of the South African police when apartheid ended (and had likely given the order for the memory purge). The brigadier said he had told the general that, rather than destroy their archives, the Security Police should have used their slush funds to send those records to their allies in Israel and Taiwan for safekeeping. ‘Today we need these things, because so many guys come and say “I was a freedom fighter.” And he wasn’t! … Now we can’t prove it,’ the brigadier said.

I did not share his positivist faith in archives as bearers of the truth, which is why I was not interested in the identities of the police agents, informers, and sources whose code names I had found. But I was interested in what each code meant. If his indignation revealed the passions aroused by the memory purge, it also crystallized the historical and political significance of the object that is the subject of this book. This object, a secret compendium of mug shots that the Security Police called the ‘Terrorist Album’, was among the documents marked for destruction. This was arson, thundered the brigadier. His thunder was, at one level, a historian’s lament over the loss of an archive. But it was also a partisan’s dirge over the loss of advantage in South Africa’s wars over the country’s unsettled history. He was angry about the loosening—unintended, to be sure—of the past’s grip on the present. If I had been in any doubt about the necessity of sifting through the remnants of the apartheid security archive in con temporary South Africa, the brigadier’s anger (and his reasons for it) revealed the stakes of the historical inquiry essayed here.

The brigadier believed in the moral and political correctness of what the destroyed material had done in the past (which was to document individuals and their actions) and in its potential to act in the present (to unmask spies and blackmail former apartheid agents). His anger helped me realize that the album that frames this study is important not simply for what it was (its materiality, if you will) but also for what the police made it do and expected of it during the most violent period in the history of modern South Africa. If the brigadier’s indignation surprised me, however, his assumptions about what the Security Police could and could not do did not.

In the years it had taken me to conduct the research presented by this book, I had become used to former security policemen believing in their own omniscience. I had heard enough policemen tell me how efficient they had been—so good at keeping an eye on their enemies, some said, that they could read in real time every fax sent from and to the ANC’s head office in Lusaka, Zambia, and could tell you what each ANC leader had for breakfast on any given day. So beholden were these men to this myth of efficiency that they had come to believe that it had extended to the destruction of their records. They believed that, because they had set out to destroy every record, they must have done exactly that.

Ironically, scholars of South Africa’s contemporary political history (myself included) have lent this myth credence by taking claims of Security Police efficiency at face value and, worse, neglecting the relics of the apartheid security archive that dot different parts of South Africa—from the tormented bodies of its inhabitants, to the dusty storerooms of its contested archives, to the landscapes scarred by some of the worst political violence recorded in the twentieth century. This book gives the lie to that myth. My presence in the brigadier’s living room that October day disproved the idea of a police force so efficient it had destroyed every record it had ever held.

There I was, after all, not just working with physical objects (an album, confidential police correspondence, informer reports, photographs, secret memoranda) that had survived the memory purge but asking these men to decipher for me the bureaucratic hieroglyphics that marked these relics. This book bears testimony to the failure of the Security Police and, by extension, the apartheid state to obliterate the past. The album at the heart of this book matters because of what it was and because of how the police used it. But it matters also for what it tells us about how those sections of the apartheid bureaucracy charged with the exercise of its monopoly on violence worked. This is not to say that this book treats the thousands of mug shots in the album as straightforward evidence of history or, to use the words of Martha Sandweiss, as self-evident transcriptions of fact. They are not. As John Tagg reminds us, photographs are themselves the historical. They are not mere illustrations.

Like the tons of records that the Security Police and other apartheid operatives fed into industrial furnaces in Johannesburg and Pretoria in the early 1990s, the album bore a taint of criminality that these agents sought to erase. They failed. This book records that failure. It also records the pain of those whom the album branded terrorists. It documents the tragedy of households torn asunder by men who did not hesitate to destroy families (by turning father against son in two cases documented in the following pages) even as they claimed to be acting in the interest of volk en vaderland. The album was no mute prop in the South African drama but itself an actor. This book documents that drama, and does so at a perilous moment in how we remember the history of apartheid. It comes at a time when memories of the apartheid past and its depravities threaten to disappear forever—unless we, taking inspiration from Walter Benjamin, recognize and seize them in the present.

If the men who invented the Terrorist Album had had their way, this book would not exist, for there would be no album to look at. But it does exist. So does the album, even if as nothing more than a remnant. It is probably for the best that we have only remnants—slivers of what was once a massive physical archive. Unlike the men who tried to reduce this archive to ashes, we cannot afford the luxury of assuming that only a total archive could tell us how apartheid corrupted individuals, ruined lives, and destroyed a country. We cannot assume that our understanding of South African history would be different if we had the total apartheid security archive (assuming there is such a thing as a total archive) to explain to us what the prefixes HK, RS, and OTV meant, and to tell us who the individuals were who operated under the cover of these codes. Even if we did have access to the lost archive, we could never ask it direct questions and hope to receive straight answers about the past. We could never ask the album, even if every copy of the 500 made still existed, to tell us something definitive about the past. Archives cannot do that. This is why we should not despair that all we have left are relics. They still have a lot to say. Writing in a different context, Theodore Adorno makes an observation that applies just as well here: ‘One should never begrudge deletions. The length of a work is irrelevant, and the fear that not enough is on paper, childish. Nothing should be thought worthy to exist simply because it exists, has been written down.

~~~

About the book

‘In The Terrorist Album, Jacob Dlamini has managed to reconstruct some of apartheid South Africa’s most violent and disturbing episodes, despite the former regime’s extensive efforts to erase its crimes and cover its tracks. Using archival evidence and detailed interviews with both perpetrators and their victims’ families, Dlamini, a superb historian and memoirist, has excavated a story that otherwise would have been hidden and forgotten.’—Sasha Polakow-Suransky, author of The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa

‘The Terrorist Album is wise, humane, and thoroughly original. With one compelling artifact, Jacob Dlamini opens worlds: of history, of biography, of the archive, of photography and philosophy. With characteristic flair and insight, he offers a compelling narrative of the workings of repressive violence and the way human beings are crushed by it, or manage to transcend it.’—Mark Gevisser, author of A Legacy of Liberation: Thabo Mbeki and the Future of the South African Dream and Lost and Found in Johannesburg: A Memoir

An award-winning historian and journalist tells the very human story of apartheid’s afterlife, tracing the fates of South African insurgents, collaborators, and the security police through the tale of the clandestine photo album used to target apartheid’s enemies.

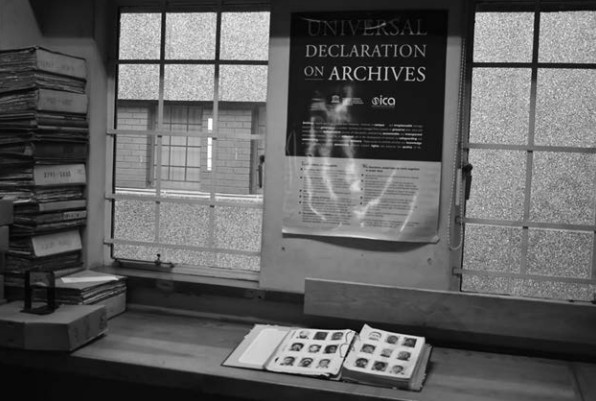

From the nineteen-sixties until the early nineteen-nineties, the South African security police and counterinsurgency units collected over 7,000 photographs of apartheid’s enemies. The political rogue’s gallery was known as the ‘terrorist album’, copies of which were distributed covertly to police stations throughout the country. Many who appeared in the album were targeted for surveillance. Sometimes the security police tried to turn them; sometimes the goal was elimination.

All of the albums were ordered destroyed when apartheid’s violent collapse began. But three copies survived the memory purge. With full access to one of these surviving albums, award-winning South African historian and journalist, Jacob Dlamini investigates the story behind these images: their origins, how they were used, and the lives they changed. Extensive interviews with former targets and their family members testify to the brutal and often careless work of the police. Although the police certainly hunted down resisters, the terrorist album also contains mug shots of bystanders and even regime supporters. Their inclusion is a stark reminder that apartheid’s guardians were not the efficient, if morally compromised, law enforcers of legend but rather blundering agents of racial panic.

With particular attentiveness to the afterlife of apartheid, Dlamini uncovers the stories of former insurgents disenchanted with today’s South Africa, former collaborators seeking forgiveness, and former security police reinventing themselves as South Africa’s newest export: ‘security consultants’ serving as mercenaries for Western nations and multinational corporations. The Terrorist Album is a brilliant evocation of apartheid’s tragic caprice, ultimate failure, and grim legacy.

About the author

Jacob Dlamini is a revered South African journalist, historian and author. He is currently an assistant professor of history at Princeton University. He was also a researcher at the University of Barcelona, a Ruth First fellow at Wits University, and received a doctorate in history from Yale University. He was the political editor at the Business Day newspaper and a columnist for both that paper and the now defunct The Weekender. His books, Native Nostalgia and Askari, the latter of which won the 2015 Alan Paton Award, were both bestsellers in South Africa and internationally.