Zukiswa Wanner reflects on her recent visit to the Democratic Republic of the Congo for the Fête du livre de Kinshasa.

Perhaps it’s fitting that I arrive in Kinshasa on Valentine’s Day.

I don’t think of myself as a romantic but it’s possible that my mind is automatically wired, because of the date, to fall in love with the city.

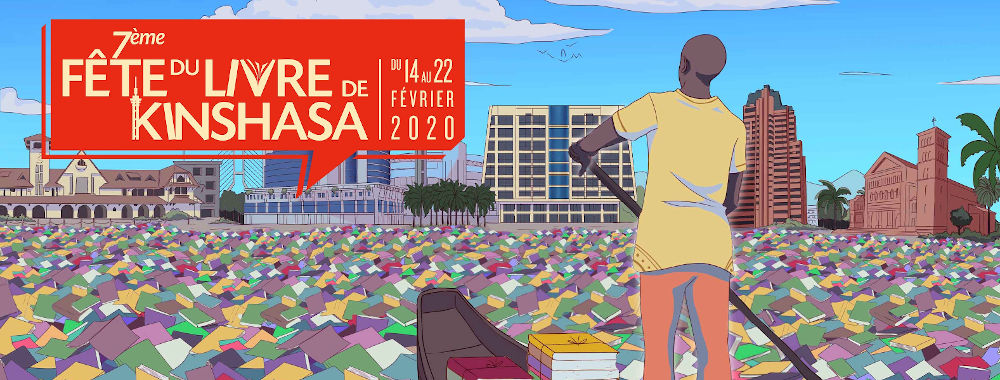

It’s late afternoon when I get to the Grand Hotel Kinshasa where I shall be lodged for a week for the seventh Fête du livre de Kinshasa. For my Anglophone friends who may be wondering what this thing is I am talking about, all I can say is … The Danger of a Single Colonial Language. And this despite my own mediocre French.

From the relatively small airport—relative to OR Tambo, Murtala Muhammed and Jomo Kenyatta International—to the hotel, I feel as though I have passed through four neighbourhoods: the average, the poor, the industrial and the vulgarly rich, where the hotel is. Here you find the government offices, the international NGOs, the black folk who ‘are so articulate and speak French so well’, the international schools and, yes, the embassies.

Joseph, who picks me up from the airport, apologises for the horrible traffic in his city as though he is the cause of it. When I get to my hotel two hours after landing, this is what I conclude about Kinshasa traffic:

My inner Joburger, Lusakan and Hararian agrees and is outraged.

The Lagosian and Accran in me says, ‘Yup. Traffic. Like home.’

But the Nairobian and Kampalan in me laughs out loud and asks, ‘Umm. What traffic?’

One thing that hits me right from the airport is the multiplicity of DRC flags in every little space. At a roundabout, a police station, on a street peddler’s outfit. It’s as though my Congolese siblings were caught unaware by a national identity, but having now been made aware of it, they need to assert it all the time. I pass the national police headquarters, which display a statement about how police are courteous and helpful. It’s my loudest laugh since landing in Kinshasa. I note this because by day eight, when I leave, I will have revised my opinion on one of these things, and forgotten the other.

On my first day in town, Cameroonian–Swiss writer Max Lobe is on stage for a festival event with Congolese novelist Koli Jean Bofane. My French is mediocre but not so mediocre that I can’t figure out how hilarious Max is. We don’t hang out nearly enough before he leaves, but he has officially become my Francophonie Frankie Edozien. And if this comparison bothers you, I sincerely apologise. Kinshasa has me comparing everything Anglo to Franco in a way I have never done before. And I wonder whether my centring it around Kin and Lagos doesn’t have something to do with both cities believing THEY ARE AFRICA. A character in the short story ‘Ahmed’, by ‘the Mayor of Lagos’ Toni Kan, says of the city: ‘see Lagos and die’. Essentially, once you have been to Lagos, there is nothing more to live for. On the other hand, a character in Richard Ali A Mutu’s novel Mr Fix-It states: ‘You may live to be one hundred years old, but if you have never seen Kinshasa, you cannot say that you have truly lived.’

For the longest time I publicly stated that the problem with this continent was that Nigeria thought it was Africa and South Africa though it was not in Africa, and if these two, our alleged strongest economies, could alter their perception, this continent would be winning.

I’d like to revise that.

Nigeria AND Democratic Republic of Congo think they are Africa, and South Africa AND Egypt think they are not in Africa.

See our lives.

That said, the next few days in Kinshasa are full of some crazy adventures beyond the literary.

On my first full day, I ask one of the writers who contributed to the recently published Afro Young Adult anthology Water Birds on the Lakeshore, Merdi Mukore, to show me Kinshasa beyond the bourgeois space I have experienced so far. We are joined by Jocelyn Danga, one of the writers who qualified for an Afro Young Adult writing workshop (FYI, Anglophones, Jocelyn is a dude) and a poet, Negue Fly.

Bandal.

That’s where it’s at.

We eat.

The most delectable street cooked food ever.

That chicken?

Melts in my hands, before I scoop it in my mouth (with apologies to that nineties emcee Candyman).

No braai, no suya, no nyama choma can bloody compare.

I start thinking that if this is how the bonobos are prepared, no wonder there are only twenty thousand of them remaining.

Because … culinary magic.

The Francophonie family has us beat on these food streets.

Anyway …

We drink.

Two guys have Maltina. A guy and a woman have Tembo.

We dance to Fally Ipupa (because this is actually the hood of his origins).

It is, as the youngsters say, ‘lit’.

And then we decide to walk through the neighbourhood.

My Nigerian family has said to me, ‘Zooks. You be hard.’ And I believed it.

Turns out they were buying my face.

As we walk, we encounter a gang that I will later learn is called the Kuluna gang. The etymology of Kuluna is from ‘colony’. And they claim their territory, alright.

Here’s what happens.

Three men.

Shirtless.

With whips and machetes.

Everyone scurries into kiosks to try to close themselves in.

My party of four does that too.

Except …

Two of the three follow us.

‘You are not from here,’ one of the two says.

‘Yes we are,’ Negue Fly says. And before he can think of something else to say, whoosh, a whip hits his face.

My maternal instincts come into play and I attempt to cover him.

Too little, too late.

When the Kuluna gang leaves, we dash out of there.

His forehead is swollen. We go to the nearest pharmacy and buy him some aspirin, and then proceed to look for ice in a supermarket so he can put it on his forehead.

Later, we will laugh about it.

A friend will ask me why we are laughing.

And I’ll respond, ‘Because we laugh so as not to cry. And we fear fighting. Our governments have put us through this.’

And when I listen to myself, I cry inside.

In the next week, I shall visit an orphanage for the bonobos, now an endangered species. I shall eat many more delicious foods, once while watching Champions League soccer at a no-frills outside bar with many of the writers who are part of the festival. I shall talk to students and adults and many times I shall be asked the question all South African artists dread when elsewhere on the continent: ‘Why are South Africans xenophobic?’

But there shall be beauty too. In one of his short stories, my friend Troy talks of Kin la Belle. Despite all its mess, Kinshasa deserves the nickname ‘the beautiful’. It’s the way people turn up and pack places out even when it’s raining because they have taken ownership and feel part of a literary festival. It’s the fact that, for all the misgovernance, there is an avenue in Gombe lined with works of art, which no one has messed with, even after the tumultuous times the country had after its elections. It’s in the way that one afternoon, when I decide to take a moto from a library to my hotel, and the rider wants to overcharge, a policeman comes over and tells me he will negotiate a better rate for me with someone else. It’s in the way that there is an artistry put into everything by Kinshasans—in music, in dress, in food. I visit three schools from different economic brackets and the city’s beauty is reflected in the way the young men and women I talk with assert themselves and voice their opinions.

And yet I know there is another side to Kinshasa that is less pretty. The side that makes unemployed young men join the Kuluna gang, and makes one think twice before going to the market. The side that pushes women into the oldest profession because there is no other way to earn a living. There is a Kinshasa where a First Lady isn’t ashamed to state that she will give top students fully funded scholarships to France, instead of asking her husband to ensure that the education system is functional enough that no one need go to France or Belgium except by choice.

But then, which city doesn’t have faults?

As I leave Kinshasa a week later, a part of me stays with the city, in the same way I seem to leave a piece of myself in every city I love. I will return, I promise Kin the beautiful, not to take back the part of me I left, but to get to know her better than I could in one week.

- Zukiswa Wanner is an author and founder of the publishing house Paivapo.

Excellent!