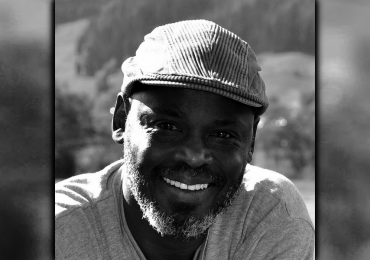

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin is a bestselling, award-winning writer originally from Kassala in eastern Sudan, but currently based in Austria, where he lives in exile after escaping persecution from the regime led by Omar al-Bashir. His works include the short story collection At the Peripheries of Sidewalks (2005) and novels The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth (2009) and The Messiah of Darfur (2013).

In 2009 Sakin won the distinguished Al-Tayeb Salih Prize for Creative Writing and, more recently, the 2017 Prix du livre engagé de la Cène Littéraire.

Lebohang Mojapelo spoke to Sakin about the 2019 Sudanese Revolution, the current political atmosphere in the region in relation to freedom of expression, as well as what he thinks justice looks like for the Sudanese.

Lebohang Mojapelo for The JRB: You are perhaps one of Sudan’s most prominent writers and yet most of your writing is banned in that country. With the heavy censorship surrounding your work and with most of your books never having been published in your country, how did your literary reputation come about?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: It is to some extent, a complicated issue to explain, but there are many factors that have to be mentioned: like the local illegal publishers, who are working in the dark, away from the eyes of security men. I call them the ‘ghost publishers’, who make very poor copies, sometimes they destroy the texts, but they make my banned books available in nearly all of the cities and villages of the Sudan. However, it is not because they are keen on literature, they are only running after profits. The other means used to break down the government’s siege around my books are the free PDFs that I make available for everyone who has access to the internet and is able to read. Also, my official publishers in some Arabic countries, like Egypt, Tunisia and South Sudan, make it easier for the Sudanese diaspora to buy my work. Nowadays, neither dictators nor censorship laws or police can barricade a writer from his audience. The wings of the letters have flown away.

The JRB: Your work is dedicated to highlighting marginalised communities in Sudan. You write of the Jungo population in The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth and the Darfuri in The Messiah of Darfur, who have experienced a form of ethnic cleansing by the Sudanese government for years. Additionally, in 2017, you won the Prix du livre engagé de la Cène Littéraire, an award for writing that is committed to social justice. What do you think of the Sudanese revolution of last year and do you have any hope of changes for these very communities you write about?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: Of course I have hope. I believe in the future. When I remember the bloody era of former president Omar al-Bashir’s regime, I have no other choice than to support our weak post-revolution government. It was too hard of a time for my people to endure. We experienced an extremely racist political Islamic military regime. They killed, tortured, displaced and imprisoned more than one million persons. They committed war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity and, as a result, as everybody knows, the ex-president and some of his warlords and civilian mobs are being claimed by the International Criminal Court.

We, as Sudanese intellectuals and artists, have to fight for our people and for a good future for our country. I used the weapon that suits me and which I know best, which is the ink. Some of us went to the battlefield to defend our families, some led demonstrations and sit-ins side by side. But also, there were some intellectuals and artists who stood beside the dictator, and prolonged his life. I am a committed writer. So, it was not unexpected to win the Prix du livre engagé de la Cène Littéraire.

The JRB: In The Messiah of Darfur we have Abderahman, a woman on a determined hunt for revenge against the Janjaweed who have been terrorising her people for years. Although seemingly extreme, to a certain extent it parallels what the people of Darfur have experienced from the government militia. Last year, Omar al-Bashir was sentenced to two years in detention for corruption. This is clearly not sufficient, and there are still calls for him to be taken to the International Criminal Court. What do you think is the ideal process of justice for the people of Sudan?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: Abderahman lost hope of being protected by the government or by any power she knew and believed in. She understood that nobody could avenge her family and people, not even her husband, and she also understood that it is only the weak and disappointed who forgive. As long as there is no justice recognising her pain and agony, taking revenge is her human right.

I think Omar al-Bashir must be sent to the ICC, there are no other reasonable options for his case. The judicial system in Sudan suffers from a thirty-year heritage of abuse and destruction by an Islamic regime. It was the tool that was used by the ex-government to oppress and persecute the opposition, or so-called the enemies of the ‘Islamic cultural project’. One of the weakest elements of this government is that two of al-Bashir’s generals, who committed war crimes in Darfur and are well recognised by the ICC, are now part of the post-revolution temporary government! The question then becomes: who will judge whom?

The JRB: In a previous interview you said ‘I write to expel my fear of war’, and your writing techniques are incredibly experimental: a mixture of tragedy, comedy, magical realism and the superstitious. How do these writing styles help in your exposition of the difficulties of oppression, censorship and the violence of a brutal regime? Do you succeed in expelling your fear?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: The African American writer Toni Morrison wrote about the styles that authors use to turn elements into aspects of language: ‘the ways they tell their stories, fight secret wars, limn out all sorts of debates blanketed in their text’. That is what I do. For me the novel is not the tale but the technique you use to tell the tales with, which is why writers tend to be experimentalist: trying to bridge this gap between thoughts and feelings and what language permits. As for expelling my fear, let me tell you frankly, as long as I continue writing, I experience a new type of fear every time I write.

The JRB: The women of Sudan are central to your work, with my favourite characters being Alam Gishi in The Jungo: Stakes of the Earth and Abderahman in The Messiah of Darfur. And as we saw during the protests in Sudan, there were many women who were vocal and were leading the cause. Do you feel women unfairly carried more of the burden of the oppressive systems of the previous Sudanese government?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: Yes, exactly. All Islamic regimes oppress women through sexism and false interpretations of the Qur’anic texts. For them, women are nothing more than children-making machines and amusement-deliverers to men. The ex-government initiated laws designed specially to limit women’s personal freedom, like what to wear, how and when. They were afforded no sexual freedom, and yet the government would send some of them as sex jihadi to amuse the mujahidin who were fighting in South Sudan against the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. They called those women Akhawat (Sisters’) of Nusaiba. Women were abused and oppressed more than men; they were the most vulnerable sector in the Sudanese community and were directly affected by deteriorating ethical and economic status. Historically, women used to be pillars of the modern Sudanese community and the queens and war leaders of ancient Nubia. Therefore it was not surprising when they led the demonstrations against al-Bashir’s regime and were leading the cause: they were fed up!

The JRB: Currently, Sudan is being governed by a council made up of members of the military, civilians and protest groups in what is considered to be power sharing. Is this what Sudan needs?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: This council is a temporary institution, with very limited authority. In fact, it is a big shield that protects the military warlords, who were part of the ex-government and were assassins and rapists. The head of the council is famous for his bloody sentence: ‘I am the superior God of Darfur, I kill and let live according to my will.’ His deputy is the chief of the Janjaweed militia known as Hemedti, responsible for killing, displacing and raping thousands of civilians in Darfur. So the lords of war who initiated this council may face the same fate as their leader Omar al-Bashir. The suitable place for those leaders should be prison or the ICC. They were the tools used by al-Bashir to commit his crimes. People in Sudan don’t trust them, on the contrary, they fear their power. The post-revolution government is too fragile and weak to get rid of these military figures.

The JRB: You went into exile over six years ago, fearing for your life, and currently live in Austria. Have other artists in Sudan faced similar fates, and are there signs that freedom of expression will once again be established in Sudan?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: I am not the only one who has been sent to exile, but tens of intellectuals and writers have been exiled as well. Now almost all the laws that limit freedom of expression are cancelled in Sudan, along with some Islamic laws.

The JRB: With al-Bashir’s exit, and a new dawn on the horizon, are you considering going back and making your home in Sudan again?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: Yes, but not now, as long as the perpetrators and the killers are still part of the government. But I am eager to see my friends, my family, my old house and the beautiful crazy river that runs near my village since the world began. Sometimes nostalgia is stronger than fear.

The JRB: In 2015, al-Bashir came to South Africa for an African Union meeting, and even though there was an international warrant for his arrest issued by the ICC, South African leaders enabled his safe passage back to Sudan. What has been your experience of Pan-African solidarity with Sudan (or the lack thereof) as a citizen and writer?

Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin: You know, African leaders are a gang. Even when they claim to be Pan-Africanists. They have these vivid ideas about solidarity—nice to read and to listen to, but they are just what Frantz Fanon describes as ‘black skin, white masks’. Except Thomas Sankara and Patrice Lumumba—I don’t know what they would have become had they lived longer.

For me, as an African writer I have experienced solidarity with my African audience and peers everywhere, through my books that have been translated into English and French or Swahili, and I have also been fortunate enough to be invited to many African literature conferences all over the world. Right now, I am supervising an important project in Ethiopia. It is an anthology of Ethiopian literature written in local Ethiopian languages like Amharic–Argobba or Tigrigna. The anthology will be published in Amharic, English, French and Arabic.

The JRB: We will look out for it. Thank you for your time.

- Lebohang Mojapelo is an editor, writer, researcher and poet based in Johannesburg. Follow her on Twitter.