The JRB presents an excerpt from Politics and Community-Based Research: Perspectives from Yeoville Studio, Johannesburg.

Politics and Community-Based Research: Perspectives from Yeoville Studio, Johannesburg

Edited by Claire Bénit-Gbaffou, Sarah Charlton, Sophie Didier and Kirsten Dörmann

Wits University Press, 2019

About the book

Politics and Community-Based Research: Perspectives from Yeoville Studio, Johannesburg provides a textured analysis of a contested urban space that will resonate with other contested urban spaces around the world and challenges researchers involved in such spaces to work in creative and politicised ways.

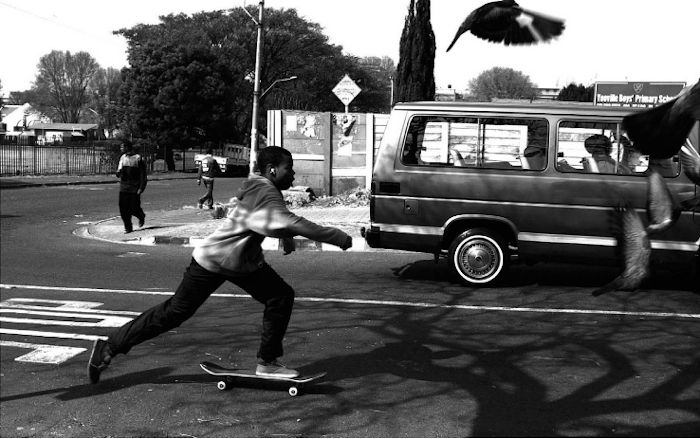

This edited collection is built around the experiences of Yeoville Studio, a research initiative based at the School of Architecture and Planning at Wits University. Through themed, illustrated stories of the people and places of Yeoville, the book presents a nuanced portrait of the vibrance and complexity of a post-apartheid, peri-central neighbourhood that has often been characterised as a ‘slum’ in Johannesburg.

These narratives are interwoven with theoretical chapters by scholars from a diversity of disciplinary backgrounds, reflecting on the empirical experiences of the Studio and examining academic research processes. These chapters unpack the engagement of the Studio in Yeoville, including issues of trust, the need to align policy with lived realities and social needs, the political dimensions of the knowledge produced and the ways in which this knowledge was, and could be used.

Read the excerpt:

Introducing Yeoville: Context and representations

Greater Yeoville (hereafter, Yeoville), which includes the suburbs of Yeoville, Bellevue and Bellevue East, is located north-east of the inner city, and is part of the City of Johannesburg’s Region F, which broadly encompasses the central business district (CBD) and the inner city. This peri-central neighbourhood, located only a couple of kilometres from the CBD, offers a built form and urban structure very distinct from neighbouring inner-city Hillbrow, which is easily identified by its residential high-rises in the Johannesburg landscape. It also stands in contrast to the lower-density mansion landscape of Observatory (Meyer 2002), further east of Yeoville and the CBD, starting at De la Rey Street. To the south, where it abuts the Ridge, Yeoville offers spectacular views of the CBD and Doornfontein, and to the north, it is bordered by a major artery of the inner city, Louis Botha Avenue, currently being redeveloped under the City’s Corridors of Freedom Development scheme around the extension of the Rea Vaya bus-rapid-transit network (City of Johannesburg, undated).

The dense urban fabric of Yeoville is structured by a tight grid of narrow streets separating blocks of 50 x 100 metres, subdivided into, at the most, 20 plots. The area’s building stock includes two- to four-storey apartment buildings, some of which are fine examples of the Art Deco period of Johannesburg (such as the Beacon Royal on Grafton Road), but most of which stem from the occasional 1960s and 1970s style of plot redevelopment that spilt over from neighbouring Berea (such as the Ralton Corner block of flats on Raleigh Street). Most of the building stock, however, consists of earlier, Edwardian detached houses with tin roofs and stoeps (front porches) located on tiny plots that often get subdivided to accommodate the construction of a number of backyard rooms and extensions. The general feel of the streets is that of a walkable and agreeable Joburg suburb, offering a distinct urban quality and a good balance of street atmospheres. The quiet and shaded Muller Street, lined with jacarandas and detached homes, for example, contrasts with the ever-busy Rockey-Raleigh Street, which acts as the main commercial and transportation spine. Most of the neighbourhood shopping activity is concentrated in Rockey-Raleigh Street, which is a composite of a string of 1900s canopied shopfronts housed on the ground floors of old one-storey buildings on the eastern end of Raleigh, banal 1970s mid-sized chain stores and restaurants such as Shoprite or Nando’s, and the covered produce market built by the Johannesburg Development Agency (JDA) in the late 1990s. These formal areas of commerce are complemented on most of the residential streets by tiny spaza shops (informal convenience stores) carved out of residential units and offering basic sundries to their customers. Small restaurants and taverns abound in the area, some clustered in the corner block of Time Square, some developed from detached units on the main arteries. They cater to different communities of African customers, giving Yeoville its unique attraction as a meeting point for foreign-born Africans in Johannesburg and beyond. Finally, numerous private schools, churches of all denominations, a police station, a swimming pool, several public parks and public amenities (such as the Recreation Centre restructured in the early 2000s by the JDA), as well as a taxi rank and numerous bus stops add to the neighbourhood’s inner-city quality. A self-contained neighbourhood full of resources and public amenities, and well connected to the employment markets of downtown Johannesburg, it contrasts sharply with under-serviced communities in the peri-urban areas of the metropolis and raises very different questions in terms of public intervention.

Transformations

These coexisting generations of the built form as well as the functional mix are testament to a neighbourhood which has seemed desirable for several generations of Joburgers. Yeoville and Bellevue were founded in the early 1890s, and quickly attracted a working-class white population searching for housing opportunities close to the CBD (Roux 2010). The 1920s saw an influx of Jewish residents who had fled the European pogroms and settled in South Africa or simply relocated from more central areas of the city (Rubin 2004). In the following decades, Yeoville acquired its identity as a middle-class and aspiring neighbourhood, fairly tolerant and cosmopolitan (Harrison 2002). South Africans of southern European origins also chose Yeoville for residential and business purposes. Still, the Group Areas Act implemented in the 1950s profoundly altered this image of inner-city possibility for most non-white residents, who were barred from accessing the residential opportunities of the neighbourhood until, eventually, the growing contestation of the apartheid regime in the 1970s reconnected Yeoville with its tolerant tradition. A growing influx of black African residents (Jürgens et al. 2003) matched the rise of a booming cultural and deeply political scene. Yeoville evolved from a quiet suburb into a night-time hotspot in that period, with the opening of jazz and rock clubs such as Rumours in the 1970s, the Black Sun and La Tortu in the 1980s, as well as the short-lived jazz club of Hugh Masekela located in Piccadilly Centre in the early 1990s.

From the late-apartheid period onward, Yeoville’s residential dynamics were in fact no different from that of the whole inner city, which became home to increasing numbers of black urban residents hailing from the city’s townships and also from outside Johannesburg (Morris 1999; Guillaume 2001; Beavon 2004). Simultaneously, the white middle-class residents moved en masse to the northern suburbs, attracted by new suburban lifestyles as much as fleeing from what was perceived as increasing urban decay. This process was exacerbated when banks began redlining buildings in the inner city, preventing potential owners from acquiring property in the area. In the context of these very complex and superimposed demographic movements, for those who had left these neighbourhoods (or had never experienced them) a simplified narrative of fear and loss emerged around the inner city, rooted in fears of crime and, often, xenophobic suspicion around the African migrants who began to congregate in Johannesburg’s inner city. To a large extent this overarching narrative remains in place, 20-plus years on.

Over the years, census results for Yeoville show the racial transformation of the neighbourhood, with the proportion of self-identified black residents growing from 9.8 per cent in 1980 to 78 per cent in 2001, and the proportion of white residents falling from 89 per cent in 1980 to 15 per cent in 2001 (Jürgens et al. 2003; Smithers 2013). Simultaneously, the shift from a middle-class to a mostly lower-class population, combined with rapid population densification similar to that of the entire inner city of Johannesburg, has contributed to transforming the image of Yeoville from middle class and aspirant to its current image as a slum.

A neighbourhood in crisis?

Due to these rapid changes affecting the neighbourhood, linked to the general dynamics of inner-city Johannesburg, Yeoville has suffered from several major issues. In the late 1990s, this prompted the JDA’s efforts to improve public facilities that had become inadequate to address the complex issues of the neighbourhood, which reflected more global social phenomena: suburbanisation and middle-class flight; migration and residential turnover; and densification and impoverishment, associated with urban decay. The Studio’s community partners identified a number of core issues that still needed addressing as priorities in the late 2000s: the lack of housing opportunities stemming from population densification, the issue of diversity and the associated difficulty of pinpointing the neighbourhood’s identity, the issue of trading opportunities and their development in both public and private spaces, inter alia. The neighbourhood is still generally reviled as ‘declining’, ‘dirty’ and a ‘hotbed of criminality’, and understood as a ‘metanarrative for crisis’ (Nuttal & Mbembe 2008). Yet Yeoville is not the most deprived neighbourhood in Johannesburg: census figures for Ward 64 (part of Yeoville and neighbouring Berea) are testament to its inner-city dimension with regards to the median income of its population—R29 400 per year, similar to that of Gauteng as a whole—a relatively high rate of employment due to its close proximity to employment resources, as well as relatively high levels of education (see table 2.1).

The number of residents in Yeoville today is unclear due to the political fragmentation of the neighbourhood into several wards, which also shapes the way census data are framed. Yeoville falls under three main electoral wards, causing community leader Maurice Smithers to argue that ‘nobody really rules Yeoville’, particularly since the three councillors belong to opposing political parties, which eventually taxes the coherence of a strategic vision for the area. Nonetheless, the population figure frequently given by community associations such as the Yeoville Bellevue Community Development Trust is about 40 000 people, the result of continuing densification since the mid-1990s (Smithers 2013). Thus, identifying what a Yeoville constituency might want and what is to be done are central in this neighbourhood with a rapid turnover of population, active but fragmented community-based organisations, and a diversity of origins frequently excluding many from traditional local political representation.

Yeoville can also be depicted, perhaps less specifically than other inner-city neighbourhoods (such as Hillbrow), as a point of entry for several generations of migrants to the city—from Eastern European Jews fleeing the pogroms at the beginning of the twentieth century, to predominantly French-speaking Africans in the 2000s, to a broader variety of migrants hailing from the African continent today (Prabhala 2008), who maintain strong social networks at various scales. In the aftermath of the 2008 xenophobic attacks, a public art initiative directed by artist Terry Kurgan (Kurgan 2013; Dodd & Kurgan 2013) aimed principally at giving foreign residents a degree of agency in their self-representation. Against the backdrop of the current contested discourse on foreignness in the country, some local activists consistently attempt to deconstruct the negativity of xenophobic discourses. Noting that the majority of Yeoville residents are currently foreign migrants¹, Yeoville activists celebrate the neighbourhood’s cosmopolitan dimension and aim to consolidate, formalise and even perhaps capitalise on what they term a Pan-African identity.

Yeoville mythology

Yeoville is specifically a part of the mythology of transitional Johannesburg—the ‘place to be’ in the early 1990s, where political activists and the artistic vanguard would gather, where apartheid segregation was defeated less via the confrontation and open struggle of the townships, than by meeting and mingling across racial lines in spaces devoted to culture, arts, music and socialising (Harrison 2002; Jürgens et al. 2003; Smithers 2013; Bénit-Gbaffou 2014). It was a very short period in Yeoville’s history, but it definitely helped define Johannesburg’s collective identity as a city. Virtually all progressive intellectuals, artists and activists have had an experience of Yeoville. Most of the School of Architecture and Planning academic staff have lived or socialised in Yeoville at some point in time; most cherish the memories of the place, linked to a key moment when history and their own trajectory intertwined, at the crossroads of freedom, youth, encounters and possibilities. This representation has also nurtured discourses contrasting the liveliness and vibrancy of Yeoville with the crime and dangers of the neighbouring area of Hillbrow—which, in spite of an urban trajectory not dissimilar to Yeoville’s, is nicknamed ‘Hell-brow’ and is still depicted, in popular fiction for instance, as the main crime hotspot of Johannesburg, if not of South Africa (see, inter alia, Mpe 2001; Beukes 2010; Moele 2011).

Yeoville dominant narratives, even when focused on crime and decay, depict it as a slum rather than a crime hotspot—highlighting its neighbourly and vibrant character despite its urban decay (Higgs 2012). Yeoville has been compared, not to Hillbrow (with all its undesirable connotations ), but to what Sophiatown was prior to the 1960s. Sophiatown, a black suburb legendary for its dynamic culture, was erased by the apartheid administration, yet attained the status of myth as ‘the creative slum’, the ephemeral and unlikely place of racial and social mix, creative arts and politics (Hart & Pirie 1984; Gready 1990; Harrison et al. 2014). It also represents, in South African minds, a form of public space that has systematically been destroyed in the past. This systematic destruction occurred precisely at the time when Jane Jacobs (1961) vigorously questioned the meanings of ‘slums’ and advocated for their urban and social value.

But Sophiatown was celebrated as an ideal neighbourhood (racially mixed, lively, arty) only after it was destroyed, in a retrospective rather than in a contemporary appreciation. While we celebrate the idealised memory of Sophiatown as a public space, we neglect to interrogate what Sophiatown might have looked like in reality. A careful examination of Yeoville represents an opportunity to understand such neighbourhoods in all their complex and contradictory dimensions. Yeoville might well be such a ‘slum’—vibrant with life, diversity and inclusion, but not without its social tensions and urban ills.

Note

1. According to the 2011 census, about 50 per cent of Yeoville residents are foreign born (quoted in Smithers 2013).

References

Beavon K (2004) Johannesburg: The making and shaping of the city. Johannesburg: Unisa Press.

Bénit-Gbaffou C (2014) Are Johannesburg peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? The local governance of diversity, mobility and competition in Yeoville and Bertrams. In Harrison P, Gotz G, Todes A & Wray C (eds) Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, pp. 252–268.

Beukes L (2010) Zoo City. Johannesburg: Jacana Media.

City of Johannesburg (undated) Corridors of freedom to change city. Accessed September 2018, https://www.joburg.org.za/departments_/Pages/City%20directorates%20including %20departmental%20sub-directorates/development%20planning/Corridors%20folder/Strategic-Area-Frameworks.aspx.

Dodd A & Kurgan T (2013) Checking in to Hotel Yeoville. Third Text 27(3): 343–354.

Gready P (1990) The Sophiatown writers of the fifties: The unreal reality of their world. Journal of Southern African Studies 16(1): 139–164.

Guillaume P (2001) Johannesburg: Géographie de l’exclusion. Paris/Johannesburg: IFAS/Karthala.

Harrison K (2002) Less may not be more, but it still counts: The state of social capital in Yeoville, Johannesburg. Urban Forum 13(1): 67–84.

Harrison P, Gotz G, Todes A & Wray C (eds) (2014) Changing space, changing city: Johannesburg after apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Hart D & Pirie G (1984) The sight and soul of Sophiatown. Geographical Review 74(1): 38–47.

Higgs C (2012) Looking for trouble and other mostly Yeoville stories. Johannesburg: Hands-On Books.

Jacobs J (1961) The life and death of great American cities. New York: Random House.

Jürgens U, Gnad M & Bähr J (2003) New forms of class and racial segregation: Ghettos or ethnic enclaves. In Tomlinson R, Beauregard R, Bremmer L & Mangcu X et al. (eds) Emerging Johannesburg. London: Routledge, pp. 56–70.

Kurgan T (2013) Hotel Yeoville. Johannesburg: Fourthwall Books.

Meyer M (2002) Civil action and space: Problems and possibilities, a case study of the inner-city suburb of Yeoville. Dissertation (Diplomarbeit), Department of Geography, University of Hamburg. Originally written in German, translated into English by the author.

Moele K (2011) Room 207. Johannesburg: Kwela Books.

Morris A (1999) Bleakness and light: Inner-city transition in Hillbrow, Johannesburg. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Mpe P (2001) Welcome to our Hillbrow. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Nuttall S & Mbembe A (2008) Johannesburg: The elusive metropolis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Prabhala A (2008) Yeoville confidential. In S Nuttal & A Mbembe (eds) Johannesburg: The elusive metropolis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 307–316.

Roux N (ed.) (2010) Yeoville: A walk through time. Unpublished research report, University of the Witwatersrand/Yeoville Studio, Johannesburg.

Rubin M (2004) The Jewish community of Johannesburg, 1886–1939: Landscapes of reality and imagination. Master’s dissertation in Geography, University of Pretoria.

Smithers M (2013) Re-imagining post-apartheid Yeoville Bellevue: The journey and reflections of a resident activist/activist resident. Research Report 6, South African Research Chair in Development Planning and Modelling, School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Wazimap (2016) City of Johannesburg Ward 64, based on Census 2011, updated 2016 where possible. Accessed April 2018, https://wazimap.co.za/profiles/ward-79800064 -city-of-johannesburg-ward-64-79800064/.