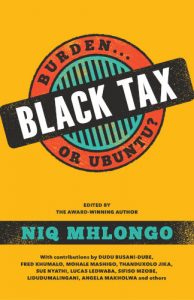

Read an excerpt from Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu, a new collection of essays edited by City Editor Niq Mhlongo.

Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu

Edited by Niq Mhlongo

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2019

In this thought-provoking and moving anthology, a range of voices share their deeply personal stories. Here, editor Niq Mhlongo, in his Introduction to the book, describes how black tax is a daily reality for thousands of black South Africans.

Read the excerpt:

‘Black tax’ is a highly sensitive and complex topic that is often debated among black South Africans. While these debates are always inconclusive due to the ambiguity, irony and paradoxes that surround it, as black people we all agree that ‘black tax’ is part of our daily lives.

This book acknowledges these complexities and tries to represent a vast variety of voices on this subject. In the process of compiling these essays, I therefore specifically tried to get a diversity of viewpoints by incorporating young and old, urban and rural, male and female contributors.

The main question posed in the book is whether ‘black tax’ is a burden or a blessing. Is it indeed some kind of tax or an act of ubuntu? The essays in this book represent both views.

In an attempt to answer this question, the idea of both the black family and the black middle class are interrogated. The point is made that as an ideological concept the black family is constantly changing to accommodate new economic, political and social realities and opportunities.

While some refer to black managers, government officials, professionals like teachers and nurses, academics and clerks as the black middle class, some contributors take issue with this categorisation. According to them there is no black middle class in South Africa, only poverty masked by graduation gowns and debts. ‘Black tax’ therefore affects every black person and not only a particular class because we are all taxed and surviving on revolving credit.

The term ‘black tax’ also isn’t acceptable to all. Many people take issue with it and say it should not be labelled as a kind of tax, but should be called something else, like family responsibility. According to this viewpoint, we need to investigate and politicise the historical roots of black tax by viewing it in the context of a racialised, apartheid South Africa.

Apartheid is seen as a system that socially engineered black poverty and loss of land for black people. This meant that black South Africans couldn’t build generational wealth. After apartheid, the capitalist system perpetuated these inequalities. For example, a black person may earn the same salary as their white counterparts, but they will have more financial responsibilities to their family, which is often still trapped in poverty due to the inequalities that were engineered by the apartheid system.

The above perspective stands in opposition to those who say that ‘black tax’ is an undeniable part of black culture and the African way of living according to the philosophy of ubuntu. A number of contributors write positively about how much they have benefited from so-called black tax and how much joy they get from being able to give back once they start earning.

Then there is also the viewpoint that links ‘black tax’ to the place and role of the ancestors. To look after family members is to keep the spirit of the ancestors alive and to ensure continuity between the past and the present. It keeps the black family intact.

Some authors therefore believe this way of life is something black South Africans should be proud of.

*

The one thing the contributors seem to agree on is that black tax is a daily reality for nearly every black South African, from sons and daughters who build homes for their parents to brothers and sisters who put siblings through school, and to the student who diverts bursary money to put food on the table back home. There are also several moving stories that refer to how people would simply open their homes to near and distant family, or even relative strangers, in need of help or a place to stay.

My personal observation is that most black people become breadwinners at an early age, some even at eighteen, and are then expected to be ‘deputy parents’. The moment we start earning we are seen as ‘messiahs’ who will rescue the family from poverty.

One especially sad theme that this collection brings to light is the dashed hopes of youngsters who aren’t allowed to study within the fields they are passionate about. Black parents expect their children to study something that will allow them to earn a high salary one day.

Linked to this are the deferred dreams of so many people who put their family commitments before their own needs. For instance, one of the contributors mentions how he couldn’t continue with his postgraduate studies because he first had to put his siblings through school.

A number of stories are testament to the resilience of the human spirit in their descriptions of grandmothers and mothers who assume the role of paterfamilias and ensure their family’s survival despite grinding poverty. Inadvertently, this adds to the debate over how black women are suffering doubly as a result of patriarchy and the demands imposed upon them by black tax.

When reading the contributions, it also becomes clear that many people feel conflicted about ‘black tax’. They point to some of its negative aspects, like people who fall into debt to keep up with their family’s expectations. They also describe the guilt trips they are put on, not only by their parents or family, but also by pastors and other church officials.

Sadly, there are also those who expect handouts and/or waste whatever is given to them on frivolous things. One contributor even goes so far as to describe a family’s unrelenting demands as ‘predatory’. This is one of the challenges posed by black tax and to me it is also symbolic of the rise and decline of the black family as a social entity.

Many South African middle-class-income households are connected to working-class families. In the context of hunger and poverty it becomes unavoidable to send money home. Therefore, the point is made that the only way the issue of ‘black tax’ can be addressed is to solve the problem of inequality in the country and to challenge class identity.

Many contributors feel that by paying ‘black tax’ they are taking over what is essentially supposed to be a government responsibility. They call black tax an alternative form of social security. The government, they contend, has a duty to address South Africa’s economic challenges of the past through affirmative action and decent education and by creating jobs.

In fact, ‘black tax’ can be seen as a form of income redistribution. Given its prevalence and influence, I think that black tax has a great impact on our economy. Thousands of people would be even worse off if it wasn’t for their employed family members helping them out.

For all these reasons, I’m surprised it doesn’t get greater official recognition, by government for instance and also in public debate.

*

The real significance of this book lies in the fact that it tells us more about the everyday life of black South Africans. It delves into the essence of black family life and the secret anguish of family members who often battle to cope.

In reading this book, I hope that most readers will be able to share in the pain and joy and reflect on our lives as black people. My great wish is that it will offer a better understanding of the social, economic and political organisation of those affected by ‘black tax’.

I see this book as an opportunity to start a necessary dialogue among black South Africans about this aspect of our reality. It is clear that the majority of us have come to the point where this social and economic responsibility can no longer be viewed merely as a part of culture. We no longer want to be trapped within the confines of ‘black tax’.

~~~

- Niq Mhlongo is the City Editor. Follow him on Twitter.

Seems like an interesting read, not just speaking to and of a black South African, but a black African in general. I’ve decided to purchase my own copy.