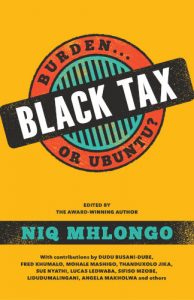

The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec interviews some of the contributors to Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu, a new collection of essays edited by City Editor Niq Mhlongo.

‘The real significance of this book lies in the fact that it tells us more about the everyday life of black South Africans. It delves into the essence of black family life and the secret anguish of family members who often battle to cope.’

—Niq Mhlongo

Black Tax: Burden or Ubuntu

Edited by Niq Mhlongo

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2019

Read the interview:

Question for Nokubonga Mkhize: In your essay you mention that the main burden many people feel when it comes to black tax is emotional rather than economic, and you also point out that ‘for many families, black tax is this huge elephant in the room that is never addressed because of our cultural background’. Do you think a book like Black Tax will help people speak more freely about the subject?

Yes. We generally do not talk about the subject of money in our families, especially black families. We think that if the family is aware of your income, you will be exploited. And in a case where the family is aware, the pressure is still there as you are expected to provide without consideration of your personal expenses.

Unfortunately, we cannot discuss black tax as just an economic issue or just a cultural issue, it is influenced by both. Young professionals do not discuss these pressures with their families as they are afraid of being called heartless or of not upholding ubuntu principals. Instead, they try to give above and beyond what they can afford to meet the expectations placed upon them, and in some cases live an ostentatious lifestyle, accumulating ‘debt to impress’ in the process.

The book Black Tax can assist as a great conversation starter among families, friends and colleagues. We are hoping that young professionals will be able to share their frustrations with their families and be able to find or share quick solutions among themselves now that this elephant in the room is being addressed. We might not have solutions yet on how to combat black tax, however having these conversations is already a huge step in the right direction. To some extent, it feels like our families believe they are entitled to this income. This will hopefully bring some awareness and understanding to this issue and educate families on the reality of a young black professional’s expenses, financial reality and pressures.

Question for Lidudumalingani: You bookend your piece with an observation about how the path of a person’s life is mapped long before they are born, and the essay is strung through with a sense of desolation and stress. But the last line states that a person’s only job is ‘to negotiate the terms’ of how they follow their life’s path. Is this a signal of hope?

The two feelings, hope and stress, form the fabric of black tax, at least for me. There is joy in putting one’s siblings through school but there is also the stress that in doing that one is sacrificing part of themselves. It is an ongoing negotiation that doesn’t promise to reach a resolve. And I want to be clear that this differs from one person to the next.

The JRB: I’m also interested in why you decided to write in the second person, ‘you’, as this seems to illustrate the ubiquity of black tax. Was this what you intended?

Not so much. The second person was inspired by two things. One, I was more invested in figuring in what other ways, forms, point of view, the tradition of the essay can take in. Two, I wanted to create distance between the text and the reader.

Question for Outlwile Tsipane: In your chapter you point out that black tax as a concept is not new, rather that it ‘merely describes something that has been happening within black society for many decades and over several generations’. But you also hint that you believe it is something future generations should not be burdened with.

In one of the essays, it is taken even further to make the point that we are born into this condition. I look at my eight-year-old child and wish that he does not have to face what we are going through and what my parents and their parents have gone through. But the rate at which the supposed change is happening does not inspire much promise.

Often, when the interrogation of such matters occurs, there are factors that I feel are not looked at properly. Surely we cannot say it is ‘ubuntu’ when a student at university shares their bursary fund money with the family back home? Imagine a situation where a woman is forced to scatter her children around the country to relatives so that they can be looked after. A clear pattern emerges here, that the issue is really systemic, and that is where it needs to be dealt with first.

The book itself largely paints an overall picture of some impact being made, perhaps here and there solutions being offered—and it is good that these conversations are happening frequently.

What I am getting at is to say that our children should not have to work ten times harder in order to make little strides in their lives. Their salaries or any other earnings should not be seen as a communal facility that can be drawn from. These are things that need to be dismantled altogether.

It is here that we can pose a question, to form a comparative analysis: Do white people go through the same conditions? There the answer is of course an emphatic ‘no’. In the South African context then, the laws and other ways from the past were made to favour white people. How many of these have been done away with to create a par path?

The cycle needs to be broken. If it could not happen for us, at least the next generation deserves to be unburdened.

Question for Monde Nkasawe: At one point in your essay, you make the point that black tax can in fact be seen as a revolutionary concept, as it ‘represents a form of pushback and rebellion’ against colonialism’s ‘attempts to annihilate the nucleus of the African family’.

Well, resistance to colonial intrusion into black society did not only happen in politically organised ways. There were also self-preserving habits that developed over time, at the centre of which is ‘black tax’. As I say in the article, black tax was or is, notwithstanding its excesses, a form of black solidarity, in much the same way as the phrase Steve Biko coined, ‘Black man, you’re on your own’. Seen in this context, black tax is actually revolutionary.

Question for Nkateko Masinga: You write that ‘in the eyes of the community, no one is successful until their entire family is successful’, which means that black tax comes not only with an economic burden, but with a psychological burden too.

A previously disadvantaged student walking through the gates of a university in South Africa represents not only themselves but an entire lineage of people who did not have access to higher education before them. To fail is to squander the opportunity and consequently to let the entire bloodline down. The psychological burden of carrying not only one’s own hopes but the expectations and desires of an entire family is immense.

In my first year at university, I learnt that there were two types of failure: academic exclusion and financial exclusion. The students who were financially excluded saved face, because nobody judged them. When the news started to spread, those who knew the situation would argue that it wasn’t these students’ fault they could not afford to pay their fees, and that if their marks were high enough they could apply for funding and return to school.

Those who were academically excluded were not so lucky: they faced ridicule and stigmatisation, because they had been given an opportunity that nobody in their family had ever got and they had not made good use of it. In the end, it is not only the psychological burden of letting one’s own family down that weighs on them, but also the thought that they have disappointed an entire community of people who were expecting them to succeed.

Question for Thanduxolo Jika: For you, black tax almost becomes symbolic of what you have achieved. Although you do describe it as something that makes your life more difficult, you also seem to see it as a way of honouring your family for what they have done for you.

I have always found it to be a difficult thing, especially during tough economic times, but I remember growing up my desire was to make things better and easier for my family. It was a way to honour my family for the contributions they have made in my life. And the ability to help others where I can, more generally, is derived from that feeling.

Question for Tshifhiwa Given Mukwevho: Your story shows how black tax extends between not only family members but also people living in the same village. You speak about how people see your published work and believe that because of those books you are wealthy, and you comment: ‘I cannot help wondering where the line is between helping and being taken advantage of.’ Have you ever considered removing yourself from the situation?

In black culture, one does not begin to exist as an individual and thus it ends there; individuals within each community are entities which form a whole. Therefore, it’s not easy to totally remove oneself from the ‘abuse’ that comes with people who through the veil of dishonesty seek help, of a sort. One can use a sieve but then in the process one errs by not sifting properly, and one can end up failing to extend the hand of help where it is needed most, all because of the ‘dishonesty’ of those who falsely profess to need help.

Question for Primrose Mrwebi: You begin your piece by comparing black tax to the land issue, in that every time it’s mentioned ‘it’s as if you are saying a swear word’. Do you think the current generation is more willing to have these kinds of debates?

Yes, I do think that the current generation is more willing to have these debates. Freedom of expression comes more naturally to them than the generation before, simply given the history and the oppression of our voices in the past.

The JRB: In what ways do you think conversations around black tax, and perhaps this book, will help?

The conversation around black tax will help enlighten those people who always think that black people are out to get free things that they did not work for. It will help people see how unfair policies during apartheid created negative perceptions about black people, and how unfair that has been and still continues to be. We all wake up every day to make sense of our lives, just like white people do.

Your content helped me a lot to take my doubts, thank you very much