On 25 June 2019, during the State of the Nation (SONA) debate, our Transport Minister Fikile Mbalula tried to impress parliament and the nation by quoting Wole Soyinka in his speech. In the hilarious video clip, which was shared widely on social media, the minister mispronounces the great professor’s name, calling him ‘Whole Soyinka’. It sounds as if the minister is reading the name for the first time in his life. Mbuyiseni Ndlozi of the EFF tries to correct the minister with a ‘point of order’, quipping ‘a whole transport minister, transporting wrong information’. The clip reminds me of a few instances where I and other authors have been victims of mistaken identity. It’s not the first time, after all, that I’ve heard authors’ names mispronounced. My friend and fellow scribe Siphiwo Mahala is called ‘Sifiwo’ by some of our friends in the USA and other African countries, where South African sounds are not in daily use. Here at home, meanwhile, he sometimes goes by the name, ‘Siphiwe’. I don’t know which one is worse, the mispronunciation of a name or its complete replacement by an entirely different one.

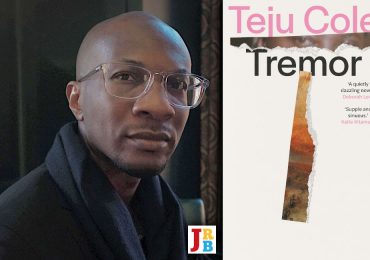

A confession. In 2011 in Saint-Malo, France, I mistook well-known author Teju Cole for my hip-hop idol Mos Def. Luckily I didn’t tell him.

But I have also been the victim of mistaken identity on several occasions—to the point where I’ve even tried to brand myself by wearing distinctive hats and the same jacket to different literary festivals. I did this so people could easily identify me. I have recently grown a grey beard and black moustache, which I’m now planning to wear forever, because being mistaken for someone can be a pain, especially for us authors. Just imagine a situation where a reader buys Siphiwo Mahala’s book, and then comes to Niq Mhlongo for an autograph—or maybe a situation in which someone tells me how much they have enjoyed reading my book Room 207. You think this is an exaggeration?

In 2004, after my debut novel Dog Eat Dog came out, I was invited to a certain French school in Johannesburg. This was the first time I got paid for speaking to learners about my work and writing in general.

Prior to my visit to this particular school, I exchange a couple of emails with the school principal. She sounds happy and keen to meet me. She asks if I can speak French and I tell her I only know the basics, like ‘je t’aime’ and ‘merci’. I arrive at the school in the morning as agreed. It’s one of those rich and beautiful multiracial schools. The receptionist ushers me to a couch and offers me some tea and biscuits.

‘The principal will be with you now,’ she says.

She then communicates with the principal via some kind of speaker to say I have arrived. In the meantime I scan through different magazines on the table. A few minutes later a dude arrives at reception. He is dressed in a nice black suit and ‘kick and bhoboza’ gatskop shoes. He looks more respectable than I do. I’m wearing my blue Converse All Stars, fading blue jeans, and a T-shirt. I envy the way the guy is dressed up. He commands respect. He also speaks French, and I assume he is either from the DRC or another West African Francophone country. After the receptionist ushers him to a couch next to me, the guy looks at me and raises his hand, a sign of greeting or acknowledging my presence. Jealous, I nod my head and sip my coffee, peeking at him over the lip of the cup.

While the receptionist disappears to the restroom, the principal arrives. She walks up to my besuited companion, smiles and hugs him.

‘Oh Niq, I’m glad you’ve honoured our invitation. The kids will be very happy to see you. They have read Dog Eat Dog and loved it. They have a lot of questions for you. By the way, you look different from your photo.’

The dude smiles and says something in French. I try to say something to the principal to let her know that I am the Niq she is talking about and not that guy in the nice suit. Unfortunately I have a biscuit in my mouth. I try to wave my hand for the principal’s attention.

‘The receptionist will be here for you in the moment. Please wait,’ she says to me, then turns to the suit. ‘Wow, I thought you didn’t speak French, Niq. What a bonus for the kids. Come, let me show you around the school first.’

In a second they are gone. I’m left holding my cup and biscuit. It’s my fault, I tell myself. I must wear a suit next time. Maybe I still look too young to be an author. Aren’t authors supposed to be old people, or dressed smartly, like that dude?

The receptionist comes back from the restroom. She is surprised that I’m still on the couch.

‘Has the principal not seen you yet?’

‘No. But some lady was here and she left with the guy that was sitting there.’

She puts her hand over her mouth, embarrassed.

‘No way. But that guy was here to ask if there are any posts open to teach French at the school.’

She quickly gets on her speaker and calls the principal. She tells her, ‘Niq is still waiting at reception.’ The principal sends another teacher to fetch me, who apologises profusely on behalf of the principal. She tells me that the principal is embarrassed to face me because of the mistaken identity, and leads me to the class where the kids are waiting.

My first case of authorial mistaken identity. Admittedly, the thousand rand I was paid for an hour’s work did soften the blow.

Another incident happened in Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo, in 2013.

I arrive at the Maya–Maya International Airport for the Étonnants Voyageurs, an international literary festival. I’m with the late André Brink, the late Mark Behr, and a few others. I’m wearing my bright yellow jacket. Our host, Alain Mabanckou, has organised some people to come and meet us at the airport. As festival guests, we are supposed to get on a bus that is already waiting in the diplomatic area of the airport. We are waiting on the airport benches, when two people come and introduce themselves as the festival hosts, sent by Mabanckou to meet us. They greet and hug everyone except me. We are then told to follow our hosts to the diplomatic corridor. I follow sheepishly like an unwanted child. I make sure I walk behind the great André Brink, just in case. Our passports are collected to be stamped for entry. As I give one of the organisers my passport, he looks at me strangely, as if to give me a warning. He reluctantly receives my passport. André Brink notices his lack of enthusiasm, and tells him in French, ‘This is Niq Mhlongo.’ The guy apologises to me, in French, and tells André Brink that he thought I was one of the people working at the airport, because of my yellow jacket. Prof. Brink laughs and translates the joke for me. I wish he hadn’t.

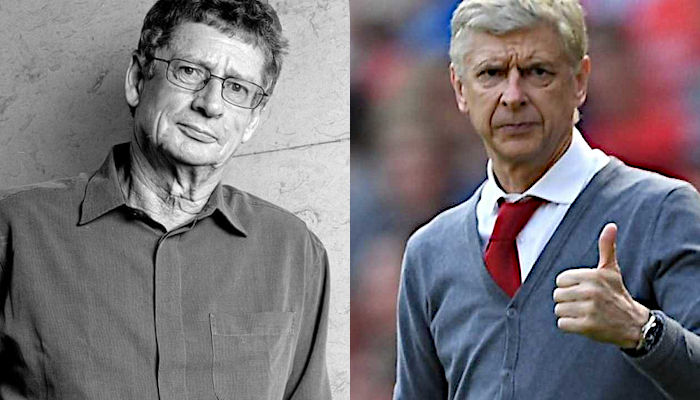

Then all is well for about two days. Every morning, at the hotel, I have my breakfast with Prof. Brink and his wife, Karina Szczurek. A few more guests arrive, including Ben Williams, Bontle Senne and Sthembiso Moloi. I notice that, every day, a group of people arrive at the hotel with soccer balls, which they kick around on the lawn in front of the hotel. On the third day, I decide to take a stroll to the swimming pool. Two people I have seen passing the ball every morning approach me, and say something to me in French. I signal my lack of comprehension, and fortunately one of the guys speaks elementary English. He tells me that the guys want me to introduce them to my coach.

‘Which coach?’ I ask.

He points at Prof. Brink. ‘Isn’t he Arsène Wenger of Arsenal?’

I have told this next story many times. It’s from the Hay Festival in Wales in 2010, and involves the literary legends Zakes Mda and Ben Okri. They are both wearing their trademark hats—you can just imagine them. So Ntate Mda and I are watching a performance by the musician Toumani Diabaté. The theatre is packed, and we are standing at the back. A few minutes later Okri joins us. The music is captivating, and we watch in silence, nodding our heads. A group of women jump onto the stage and dance to the music. An hour later, it’s the Buena Vista Social Club’s turn to entertain us. The lead singer, Eliades Ochoa Bustamante, approaches the stage, wearing his trademark cowboy hat. He strums his guitar and sings in Spanish. The crowd goes wild as the band starts playing their popular hit ‘Chan Chan’. After about five songs Ntate Mda and I decide it’s time to leave. We say goodbye to Okri by waving our hands over the sound of the music.

The following morning we are in the green room. Ntate Mda is wearing his trademark hat and we are eating our breakfast. Okri comes and stands next to our table. He extends his hand to greet Ntate Mda.

‘Morning. My name is Ben Okri,’ he is smiling. ‘I just want to say thank you for your great music last night. I had a beautiful time.’

Confused, my eyes dart from Okri to Ntate Mda and back again. The latter is not confused at all. He shakes Okri’s hand.

‘Thank you very much,’ he replies.

Okri leaves our table.

‘And then, what was that about?’ I ask. ‘But you’re not a musician?’

‘Niq, I’ve been with Ben at several literary festivals across the world. He should know who I am by now. If he thinks I look like that Buena Vista musician, that is fine.’

The moral of these stories? Go look at my latest photo, quick, so you don’t end up in one of them.

- Niq Mhlongo is the City Editor. Follow him on Twitter.