The JRB presents the winning stories from this year’s Short Story Day Africa Prize.

Egyptian writer Adam El Shalakany won the prestigious award this year for his story ‘Happy City Hotel’. Kenyan writer Noel Cheruto’s ‘Mr Thompson’ was first runner-up, and South Africa’s Lester Walbrugh’s ‘The Space(s) Between Us’ was second runner-up.

The following stories were highly commended by the SSDA judges: ‘Why Don’t You Live in the North?’ by Wamuwi Mbao (who is an Editorial Advisory Panel member and regular contributor to The JRB), ‘Slow Road to the Winburg Hotel’ by Paul Morris, ‘Outside Riad Dahab’ by Chourouq Nasri, and ‘The Snore Monitor’ by Chido Muchemwa.

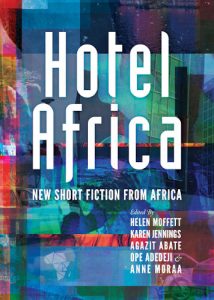

The prize is worth $800 (about R10,800) and open to any African citizen or African person living in the diaspora. All twenty-one longlisted stories are contained in this year’s SSDA anthology, Hotel Africa: New Short Fiction from Africa.

SSDA counts among the most esteemed writing organisations on the continent. Two stories from the 2013 anthology, Feast, Famine & Potluck, were shortlisted for The Caine Prize for African Writing, with that year’s SSDA winner, Okwiri Oduor, going on to win the award. Terra Incognita (2014) and Water (2015) received wide critical acclaim, while two stories from last year’s anthology, ID: New Short Fiction From Africa, were recently shortlisted for this year’s Caine Prize: ‘All Our Lives’, the SSDA winning story by Tochukwu Emmanuel Okafor, and ‘Sew My Mouth’ by Cherrie Kandie.

Read on, and enjoy:

~~~

Mr Thompson

By Noel Cheruto

1st runner-up of the 2018 Short Story Day Africa Prize

A fool who is yet to come to terms with the breadth of his foolishness. That’s who you are, Mr Thompson. A giant loophole pretending to be a person. It is the only reason I can trick you. That, and the fact that you think me foolish. The wine you sip—tilting your angular chin and sticking your slender nose up in the air—that wine is not a Chablis. You believe it is, though, so does it matter that I decanted a three-hundred-shilling bottle into an old Chablis one? I served it yesterday, as the crisp Chardonnay that went perfectly with your grilled tilapia. I will serve it tomorrow as the woody Elgin I will recommend for your dinner. It doesn’t matter what you do, Mr Thompson. You are here. I will eat off you. I am only doing what I must.

We can spend all day, Mr Thompson, going back and forth through history, trying to catch the exact moment that made me this way. We can comb through the days, sort them and stack them in piles, looking closely at each one, wondering whether that was the one that changed me. The truth is, everything did. Every event, good and bad, chipped away at my goodness. I ignored them in the beginning: a rude guest here, late salary there, long hours everywhere. Little things that did not seem to matter in the moment, but collectively, silently, they spun a web around me. One day, I woke up, and there was no me. Just a cold pile of meat hidden behind a backlog of disillusionment. I woke and drew the curtain, then closed it again when it hit me; whether the sun rose or stayed under my feet, it made no difference to me. It was the morning after I fired Nancy, the chambermaid.

There was only one word to describe Nancy—practical. Her skirts, wide, circular and falling just below her knees, were practical. Her fingers, chubby with clean square nails, were practical. Even her nose was practical; just enough nose to breathe in a practical amount of air. She was the only chambermaid then, working through the morning to turn out all twenty rooms before the midday check-in rush. Our whole operation depended on her, which was unfortunate because she was a regular no-show.

This would mean pulling on a pair of yellow rubber gloves and cleaning the rooms myself. I was young, Mr Thompson. Youth is a terrible curse, especially because it comes wrapped in naivety. I would spend the first hour of my work days dialling her number continuously. If I was lucky, she would answer irritably and let me know she was on her way. Most days, though, her phone would go unanswered. Back then, my heart was warm and crippled with feeling. I could not bring myself to fire Nancy, not even after finding out that her absence was because she moonlighted at the Regency. Her whole clan depended on her sole income.

One time, she did not come to work for three miserable days. When she finally did, I followed her around, staring at her practical canvas shoes while summoning the courage to scold her. Sometimes, especially after having had to clean up behind a particularly hairy person, I fantasised about the things I would do to Nancy. They mostly involved shouting wildly at her, then dismissing her and laughing at her tears. In reality, I could not even bring myself to look her in the eye.

I sat on the entertainment stand in Room 8, resting my feet against the back of an armchair. I watched her make the bed, spreading white linen over it by holding one edge and flinging the opposite up in the air, then waiting as it fell back over the mattress with a gentle sigh. She walked around the bed, stopping at intervals to bend over and tuck in the loose edges. She worked as though she was automated—taking the exact same number of steps in every direction. When she was done, she took a steam iron from the cupboard, sliding the door shut slowly, repeating it a little more sharply when the cupboard light failed to turn off. She winced at the clap of plywood against plywood, uneven teeth gritting, eyes sinking deep into a cluster of wrinkles.

I sat, tipping the armchair, using my toes against the back edge to play a game of balance. Nancy plugged the iron in, and it hissed into life. She flattened one half of the bedspread, then turned off the iron, walked around the bed, plugged it in on the other side and flattened the next half. Each wrinkle disappeared under a puff of steam. When she was finished, the bed stood proudly in the middle of the room, an altar of perfection.

‘Do you love your job?’ I asked, following her to the bathroom where she picked up dirty towels off the floor, gathering them into a large ball which she threw into a cart parked outside the door. My voice was high and squeaky. I cleared my throat and leaned against the bathroom door. I was afraid, Mr Thompson, that she would see that I was afraid.

‘It pays the bills,’ she said, squirting blue liquid soap into the bathtub. The white tub turned into a child’s piece of art. She crouched and used a stiff brush to scrub. I watched as white suds slowly found their way up her hands. She did not wear gloves, just bare hands, dark against clouds of foam. ‘Why, then, did you not come yesterday? You didn’t call in sick, nothing, just did not come at all. Why, Nancy?’ I shifted my weight from one foot to the next. I was terribly uncomfortable, Mr Thompson. I could see her scalp through her cropped hair. It is a terrible thing to stand over someone whom you resent and pity in equal measure. She was older than my own mother.

‘I was sick, my family was sick, we were all sick,’ she said, not looking at me, rinsing off the porcelain, cupping her hands under the tap and aiming water at particularly soapy parts.

‘That can’t be true, Nancy. Next time, pick one person and label them sick. Assigning disease to your whole family is too dramatic.’ I was trying to help her along. I was a new manager; she was a new chambermaid. Nobody knew what they were doing. We all just wanted to get by.

‘Okay, okay, only my son was sick, that’s the truth,’ she lied. I sighed, and let her off with a sharp look and a disapproving shake of the head. I could not bring myself to fire her. I found out later that she moonlighted at The Regency, and whenever the morning crew failed to turn up, she was compelled to pull double shifts. I resorted to praying hard that she would show up.

I had to let her go a few months later when I caught her going home with a packet of stolen salt hidden underneath her blouse. I was deeply shaken, Mr Thompson. I felt the cold settle deep within my bones. Here was a woman who worked seventeen hours a day every day, yet was too poor to afford salt? The system was obviously flawed. I saw it clearly in that moment. There is no justice, only tricks to keep you going. We only have one of two choices: do, or get done.

Don’t look at me like that, Mr Thompson. Our differences make us exactly alike. Should I have sought work at The Regency? Well, I did not. Probably for the same reason you chose not to stay there. I was once invited for an interview there. Right after my training, back when I foolishly believed that everyone had in them the power to make a change. I laugh at the thought now: how naïve was I? The truth is, most of us are simply pawns, moving up and down some other person’s chessboard. We live in a tragedy, Mr Thompson, but tragedies, too, can be beautiful.

Years earlier, I walked into The Regency through the back, into a long laundry room, lined on either side by silver washing machines. Ladies wearing stiff blue frocks with hairnets over their hair bent over large buckets, sorting through bed linens and stuffing them into coloured bins. They laughed and gossiped loudly, pointing me through to the exit without taking their eyes off their hands. I took a wrong turn and found myself in a large kitchen. The heat made my shirt cling to my back. Chefs in white jackets served food out of steaming pots onto plates that lined a counter against which several waiters leaned, notebooks in hand. I moved quickly, cowering at insults from a tall chef in a tall hat who screamed at me to ‘get out of my bloody kitchen now, fool!’

Nothing in my life had prepared me for the sight that met my eyes when I burst through the restaurant and into the lobby through a side door. From where I stood, the marble rolled out through the vastness of the room. The walls were made of spotless glass so that it looked as though the outside was inside. The air smelt of mint, from the drinks in short glasses on silver trays that beautiful ladies in little white dresses walked around offering to guests. It amazed me how the staff, dressed in different uniforms to symbolise their variety of roles, moved. They floated soundlessly from guest to guest, so that they looked invisible but available, as in a dream. It was obvious that I did not belong there. I walked back out, careful to avoid the kitchen on my way. No one ever called to ask me why I did not show up. My spot was probably filled before I even crossed the street.

I thought it through recently while I hid in Room 3, sipping real Chablis from a three-hundred-shilling wine bottle. I burrowed down between the crisp, white sheets and really thought about it. Why did I walk away? Would I do the same if I got that opportunity now? I really don’t know, Mr Thompson. Obviously, The Regency does not have silly problems like the accountant running off with our pay or me having to work as the manager, waiter, receptionist and everything in between. I am sure their staff doesn’t get told to ‘just put on anything black and white’ as uniforms. I also know that they have good medical cover and transport arrangements. Everything works at The Regency. The system is orderly. But you must show up every day. And work. Not walk up and down the stairs, pretending to work. That sounds like too much trouble to me. I know my way around here. I know how to get the most out of doing the least.

Do you feel the same, Mr Thompson? At three in the morning when you come in with girls a third your age hanging off your elbow? I saw you on Thursday, Mr Thompson. I did. I was there to check in the newlyweds arriving from Dubai. I told the driver to wake me when they were five minutes away, then slumped over my desk trying to catch the last of my sleep. That was when I heard giggles from across the lobby. I looked up to see four girls with big behinds stuffed into undersized pants. You were outside pulling at your cigarette before throwing it on the ground and stomping on it. The yellow taxis parked across the street blinked their lights at you, hopeful for one last fare before daybreak. One of the girls had her arm draped around your shoulder, using you as a walking stick. She was a good head taller than you, although that could have been as a result of the hideously high heels she had on.

What do you do with them, Mr Thompson? What can you do with them? You are old and hairless. Your skin has given up on your muscles and decided to gather around your elbows and knees in protest. Your back does not stay upright for more than a breath. What use do you have for a swan of giggling girls in your room? Is that why you choose to stay here and not at The Regency? So that no one asks you these questions?

I could be wrong, Mr Thompson. It could be this location that made you choose to stay here. Right in the middle of everything that you might need. Or it could be the sunshine that washes in through the tall windows as you have your morning coffee; the exact right temperature most of the year. It could also be the silence we all work hard to keep.

We do treasure the silence that rings through the corridors. That is why we choose not to have music in the lift. Yes, Mr Thompson, that is intentional. Our guests, too, are admitted by what we judge is their ability to contain their noise within their room. I made a mistake once, when my cloak of naivety was still over me. I checked in a mother with four children to Room 16.

She wore her hair in large brown ringlets that framed her face, falling just below her ears. Her hips were the width of the twin pram she pushed in front of her. Twin boys, judging from how they were clad, slept peacefully next to each other in the pram, little fingers curled affectionately around each other. A little girl hid behind her mother’s skirt, peeking up at me once every few minutes, her round eyes full of fear. Her hair was gathered into bunches that were held in place by a rainbow of rubber bands. A fourth child, a boy, the eldest, ran around the reception area, annoying and charming other guests in equal measure. He took off his shoes and started to skid from one end of the room to the other.

I gathered them into the elevator and up to their room. The mother walked beside me, chatting, at first shyly, then quickly gathering momentum every time I nodded in agreement. Within ten minutes, I knew what she was in town to do—wait for her husband, who was on his way back home from working in Somalia—and how long they would stay: three days. I settled them into their room, then went down to the basement to find spare baby cots and bassinets for her children.

It only took me eight minutes, Mr Thompson, to get back into the room. I know because when I opened the door, I was so shocked that I looked down at my watch to see how long I had been gone. The screaming reverberated off the walls so that I could not exactly tell where it came from. The mother was waiting by the dressing mirror, applying lipstick and removing it with a baby wipe. Again, and again, without thinking. Her eyes were glazed over. She must have lived through this too many times to care.

There was a splash of green on the ceiling. It looked like someone had flung a cup of green soup and smashed it against the plaster, just missing the overhead light. Bits of glass and green chunks were spread across the bed. The girl, who had stripped off her shyness like a jacket on a hot day, dangled upside down from the curtain rod shouting, ‘Call me Mowgli!’ Her little ankles, trapped in the space between curtain rod and wall, supported the entire weight of her body. She twisted her arms about, fingers wiggling in excitement.

Yet her voice was not the loudest in the room. The boy was everywhere I looked: under the wooden desk, yanking cables and squealing as they came off the wall with a sharp click, on top of the mini fridge, fingers reaching in and fishing out miniature bottles and flinging them across the room, sending the sharp whiff of good whisky up my nostrils, in the bathroom, washing his hands with shampoo and splashing it all over the mirror. The twins, who I could now see were toddlers, were on the floor, wailing.

I stood transfixed as I watched their mother calmly detangling her curls. She turned to me with a defeated look, not really asking for help. There was one poison apple in the lot, I noticed. The boy. His energy was infectious, rubbing off on the rest. All I needed to do was silence him. I tried to bribe him, catching him in the stillness between his movements and offering money, fruit, water. Nothing seemed to work. In the end, I took him firmly by the head and pulled him out of the room. This made him screech even louder. I led him out into the lobby and sat him sternly down by the window. Behind me, the rest fell into an unsure silence. The whole place was back in the quiet. We treasure quiet out here. We will do anything for it.

That is why, Mr Thompson, this is a conversation I will have with myself in my head as I watch you sip wine. I, too, am a fool. A fool who chooses to stay foolish. And when you call for me, I will ask simply, ‘How was your day, Mr Thompson?’

~~~

- Noel Cheruto is a Kenyan writer whose work has been published in Kikwetu Journal and On The Premises magazine. She lives in Nairobi.