Contributing Editor Bongani Madondo unmoors Kwame Brathwaite’s Black Is Beautiful from mono-dimensional notions of the Black Atlantic into a New African Globalism of image as sound.

‘You’ve been working in Africa?’ a girl recently asked me as we chatted on the train. ‘Do you speak African?’

‘I said yes with a straight face.’

—Peter Harrington

Black is Beautiful

Kwame Brathwaite

Aperture Foundation, 2019

1.

Can’t speak for you, but for me a book—by that I’m referring to the physical object, and if I sound snobbish here, deal with it—there is something about a hard copy with a dust jacket that lends the thing not only the status of a living organ, but imbues it with the same dramatic power.

Now it may be a terrible book—mind you I said ‘book’ and not ‘text’ … (insert tongue-sticking-out emoji here). It might be written by a fascist. Slap me, it might be a book by a bunch of academics talking in tongues to themselves (don’t ask me what happened to plain-speak, we pay for our chirrun to speak in tongues!). But a book is something to behold.

The experience can be erotic, spiritual, heart pumping, too. The first thing I do when I land my hands on a new book, I run my fingers across it for a while before slowly taking off its jacket. It obliges me, silently, revealing its next layer. This might be linen or just lean, tough, muscular cardboard. It might be black, brown, coffee coloured, pink, or white. It might have aged a bit before being opened, understanding that as a reader or viewer I, too, bring my life’s secrets to it. Or it might be sparkling new.

The front board dares you to lift it up and venture deeper, and deeper; but also cautions you to pause and wonder a moment more. You’re only privileged to open a new book for the first time once, after all.

If it’s a photography book, the secrets it comes packed with can turn this moment into an exquisite trance. I’m about to open one such book, right now: Kwame Brathwaite’s Black Is Beautiful, inclusive of context-making essays by Tanisha C Ford and Deborah Willis.

2.

There is a backstory to the photographs collected here—the central one being how the veteran Harlem photographer, now eighty-one, helped pioneer, through imagery and an appreciation for jazz and its cultural sources and prime creators, the nineteen-sixties and seventies slogan ‘black is beautiful’. The visual arc of the narrative also draws us to an understanding of how this beauty becomes manifest, at least on the exterior. In subject matter and—often, but not always—through technique, multidimensional examples of black beauty announce themselves: shimmering, defiant, mundane and ultimately human.

In the best of hands, photography, and particularly its subgenre of portraiture, pierces through the surface to reveal, or—even better—attune our eyes and ears to the secrets, the dreams even, that are locked within a subject’s interiority. Sometimes time and metaphysical conditions might coalesce to engender a silent dialogue between the person behind the lens (Brathwaite) and the one before it (often one of a variety of blacks, blue-blacks, browns, beiges … all the different types of African skin tones and textures his models from his agency Grandassa Models came wrapped in). Brathwaite’s photos achieve that with an acute, unadorned technical beauty and lyricism all their own.

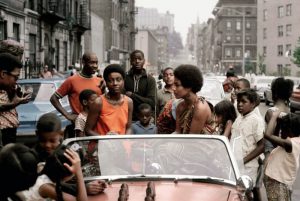

First time I laid my eyes on a photograph simply captioned ‘Grandassa Model on car during Garvey Day celebration’, I fell in love again. In love with how simplicity can fuel elegance and beauty without so much trying. This was the era of the ‘Swinging Sixties’, the age of the miniskirt. Dressed in one such mini, an African Java print, bare feet in flat leather sandals, accessorised with white DIY earrings that could have been from Johannesburg’s Mai Mai roots market circa black-to-the-future 2019, the woman is looking directly into the photographer’s eyes and, ultimately, into our hearts.

In over half a century Brathwaite’s subject was as expansive as the Black Atlantic. Models, jazz virtuosos (check Cannonball Adderley plunged on a turned-around chair mysteriously standing its ground under his gigantic frame), black protesters protesting against a white-owned shop selling European wigs to ‘Negros’ on 125th Street, jazz covers commissioned by the iconic label Blue Note: Brathwaite shot those, too.

It seems as though the selection here is in response to a curatorial mandate and archival requirement that goes beyond the standard photo-exhibition-in-a-book production. Photo books are inherently risky affairs, mostly because they concern themselves with multiple intents: technical appreciation, the timeframes within which the work was created, ideology, the subversion of the canon or the creation of a restorative project reminding audiences of forgotten faces, and so on.

Which is to say, the archival work of viewing and reviewing, as the selectors go about it, is both an exciting, present-historical adventure as well as a scary, unreliable and ultimately helpless activity, vulnerable as it is to the tyranny of the times in which a book of its nature materialises. Here, the most striking photos are those shot in black and white, with the exception of a colour portrait of a woman with an Afro as huge as a giant halo, stuck and struck against a sky-blue backdrop.

On pages 52 and 53, meanwhile, the photographer takes us on a trip to the beach.

3.

The beach images strike a special cognitive resonance simply because, especially if you are a black viewer, the business at hand, the business within the frames of both images, pretty much echoes family business.

It is as though possessed within these snapshots are family secrets you’ve known all your life, grew to be horrified by, laughed at, and in your adulthood caught yourself repeating. The story that black people everywhere take all kinds of stuff on trips to the beach. That black people have always not just packed swimwear and umbrellas as they head beachside. Or dressed in what is standardised by the mainstream as swimwear. Young men are photographed adorned in full African boubous, or track tops, with huge bags and all kinds of leisure paraphernalia in the backdrop.

In 2018, we even slaughter goats at the beach, as a misguided gesture of decolonisation. Upon a second viewing here, an aesthetic lineage that runs to current photographers emerges. The prototype of the photo featuring Jimmy Abu at Jacob Riis seaside park in Queens has looped into visual consciousness over and over again. In the Eastern Cape, nineteen-sixties to nineties photographer Daniel ‘Kgomo’ Morolong’s under-studied archive is replete with beautiful young black thangs posed in full pants. Not to be outdone, Koto Bolofo’s early nineteen-nineties Eastern Cape boys appear in chic, sponsored apparel and Ray-Ban aviators, posing for a Vogue Hommes fashion splash. In Andrew Dosunmu and Knox Robinson’s The African Game (2010), with its low-frequency, unobtrusive sponsorship from Puma, a similar set of African boys, dark-skinned, bare-chested, pretend they are not posing. The effect subverts notions of chic, of black pleasure, leisure, and joy—which may have been Brathwaite’s most central ideological statement, not only at his Queens beach but throughout his oeuvre.

One of the most fully realised images in Black Is Beautiful is also one with less than the best production quality—and that adds to its theatrical effect. It’s captioned ‘Patrons at an AJASS [African Jazz Arts Society and Studios] concert, 1956–57′, and it restates the notion that photographs have lives of their own. That they do not exist simply to satisfy curator and critics’ whims. That quality imperfection is its own beauty. That perhaps the most attuned photographers’ works tell human stories that bolt far beyond the frame. The implication, if you dare hear it, is that perhaps absence in photography is as valuable as visual presence.

The setting could have been anywhere, a dingy jazz dive in Alexandra township, or a Highlife club in Victoria Island, Lagos, or maybe a swooshy jazz salon in Renaissance Harlem, circa the nineteen-thirties. Encased within the frame, with a dark backdrop on its left side, are a total of seven neatly attired black adults, four black men and three black women on a night outing. Each has a different skin tone, and what is striking is that it is as though the photographer attentively and individually lit up each one of them in accordance with their natural skin colour. All seven are facing the camera, but it is not readily clear if the women are facing the camera upon instruction from the photographer or if perhaps their eyes are watching a jazz god on stage, behind whom the photographer may have sneaked.

The woman in a little black dress and neckwear, bordering the left part of the frame, might have been with another group of patrons altogether. She might also have given off an air that she was not that keen on being photographed, knowing her inclusion carried the potential of altering the image’s reading. We will never know.

Audiences and artists at the bar or salon have long been a staple of the best photographers, from Herman Leonard and Brathwaite to Bob Gosani and many more, dotted across the medium’s history. This specific image evokes comparison, at least insofar as its tableaux and setting, with a now-iconic Herman Leonard photo from 1948 of Ella Fitzgerald at the Downbeat Club in New York.

While Brathwaite is suggestive, never revealing the object of fascination of the spoonful of audience he snapped in their wide-eyed wonderment, Leonard is all confessional. Here, the audience, quite a distinguished set of gents, much more dapper, and largely white, is entranced by the figure of a black woman singer on stage. The gaze is double and intentional. Their eyes are taking her in from the front, and we the viewer from the side profile, as she fesses up some blues on stage. Maybe ‘Summer Time’—

Your daddy’s rich

And your mama’s good lookin’.

Other than Ella, the co-central figures here are also placed distantly. The two men are not without some frisson of power or glamour of their own. One white and grandly besuited—we know from history that’s Benny Goodman—and another, a black man, suave, dandier and clearly in some kind of kinetic dialogue with the lady on stage. We are not surprised. He is after all, Duke Ellington.

Viewing these two images a tad longer, another image, a 1983 colour sketch entitled ‘Kin Oyé’ by the Congolese artist Moké, emerges to complete an unwitting triptych, galloping over space and time. Moké seems to have distilled the two New York photographs into a single deep-colour drip sketch, again at a club we can only assume is deep in Kinshasa, run perhaps by ‘Grand Maître’ of Congolese music, Franco. Here, the night revellers have kicked their chairs slightly aside and are locked in tight embraces, the women, as with the one in Brathwaite’s image, multitasking as usual. They are conjoined with the men in the heat of, say, a Congolese rhumba, while making sure to turn their necks slightly, so as to look directly into the eyes of the invisible painter.

It’s a colour image but colour as dark-noir, all sunset scarlets, river-reed greens and sulking purples, each carrying within them a bold shade of black. The effect is astonishingly captivating. A Pan-Africanist photographer with a pronounced sartorial inclination and a penchant for black joy would have dug this. He is still alive, in Harlem. I’d look to a moment he shakes his head and wonders—What do these critics smoke?

4.

To proffer that an artist is of her times is a cliché, but often a necessary one. In this tuneful monograph—for books and images do sing: just read, or better still, listen to Tina M Campt’s Listening To Images—the photographer’s work reverberates with sonic pathos. Which is not to suggest Black Is Beautiful is one of those jazz books you’ve seen throughout the loop of your childhood and can’t take no more.

This is also not to suggest t’ain’t, for what is jazz if not the daily riddims of black beauty, anger, dreams, poses, within and without? The Barbadian-born, Bronx-bred and now Harlemite Kwame Brathwaite, ‘Keeper of Images’ as he is known throughout black, or as he’d prefer it, ‘African’ New York City, fits his times and speaks to our visual-cultural climes just as snugly as your mama’s vintage figure-hugging jacket you can never get enough of and has the names ‘retro’, ‘vintage’ and ‘classic’. However, art is not there for us to do as we please with it without it. It is implicitly, silently and yet powerfully redirecting us to its own whims, desires, and fluidities, the very attributes the notion of ownership, with its rigid proprietorial inclinations, is affronted by.

To look, nay, listen, to Brathwaite’s photographs is to grapple with their time(s) and place(s), geographically and geo-spiritually: his restless city streets and anxiety-riddled, for better or worse, home. Although he has been shooting since the late nineteen-fifties, the Hasselblad his tool, the bebop and riddim ‘n’ blues scene his haunt (now that’s the beginning of your white-boy and -girl’s rock ‘n’ roll, quite a different syncopated sonic beast from the brutally transplanted African ‘raw-kin-roll’, itself a different beast from Motown-birthed R&B, but why quibble?). Brathwaite is singularly a black, nineteen-sixties-rooted, not to be mistaken for confined, artist. But what are the nineteen-sixties to you? As per Lester Bowie’s adage: depends on what you know.

To some the nineteen-sixties commenced in ’63 with Bob Dylan and ended with Muhammad Ali and Miles Davis (both photographed by Brathwaite, although they’re not both present in the book) in ’75: Ali in his Rumble In the Jungle afterglow, and Miles riding into his controversial retirement sunset on rock and Afro surrealism’s electrified jazz. To others the nineteen-sixties did not quite arrive until the Beatles’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and did not end until that fated April 4, 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Considering the assassination happened two months after Muhammad Ali’s resolute anti-conscription statement, and in the same year as the birth of an organised Black Consciousness movement in South Africa and, as it were, at the moment Paris exploded in revolutionary praxis, 1968 might be consensually the end of, not only the decade, but also the world.

In the essay that bookends the monograph, ‘Black Is Beautiful, Then and Now’, photographer and photography historian Deborah Willis reinstates what the nineteen-sixties—Brathwaite’s nineteen-sixties—were, with a historian’s precision that also serves as a parental admonishment to us, the amnesiac generation. ‘Looking at Brathwaite’s photographs today helps the contemporary viewer imagine an explosive period and how it affected communities worldwide,’ she writes, reminding us that during that period the USA ‘witnessed an abundance of events’. The decade was ‘bookmarked by the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon presidencies, the Vietnam War, and the civil rights and black power movements—that altered our understanding of war and peace’. ‘In particular’, she says, ‘the years 1967 and 1968 proved to be the pinnacle of an era of youth-driven resistance that changed America forever.’

‘Wait—’ I can imagine future students of Decolonial Theory picking their jaws up from the floor: Black lives did not start mattering with Black Panther? While blackness is his métier as an artist, and the gift within which he lives, Kwame Brathwaite’s monograph invites us to appreciate it in its full complexity: in-your-face black defiance on one hand, and the often-maligned ‘sovereignty of quiet’ that blackness possesses on the other, as per Kevin Quashie’s insightful book title.

We can also make the case that Brathwaite and his Garveyite cohort in AJASS, but specifically as evidenced by the assemblage of photos in front of us, were ideologically intolerant and prescriptive in their promotions of beauty. But that’s to be expected where nationalism steps into the house.

5.

Carla Williams, Willis’s co-author of The Black Female Body: A Photographic History and, in a separate epistle, Bridget R Cooks, a scholar and professor of Art History at the University of California, Irvine, deliver a pair of short, sharp historical footnotes pertinent to the era Brathwaite’s work came into its own. While not profiled in the issue, his art and politics are implied within the two’s contributions to Aperture magazine’s ‘Vision & Justice’ issue, number 223, summer 2016.

Brooks holds our hands and takes us back to the contested Metropolitan Museum’s January 1969 exhibition Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America and its accompanying catalogue. She tells us the exhibition was boycotted by the very community it perhaps pretended to portray, presumably for its ‘humanist’ agenda—a well-known, ideologically-defanging liberal term that aims to curtail black agency even when it postures to talk for it—and the ‘cross cultural’ images in the show.

The catalogue’s Introduction, she tells us, written by Candice Van Ellison, was deemed ‘anti-Semitic’ and subsequently omitted from future editions. To paraphrase, the core of the controversy, as evidenced by future editions of the catalogue, was the ideological struggle over who represents Harlem and how. For example, major Harlem artists such as Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis were conspicuous by their absence, Brooks argues.

Meantime, Williams tells the story of The Black Photographers Annual, co-founded by Brooklyn-based photographer Joe Crawford in collaboration with editor Joe Walker. The Annual’s purpose was not as complicated: its creators set out to promote, though publishing, black photographers’ work. Williams paints the lineage of black monographs starkly: the first monograph by a black photographer was The Sweet Flypaper of Life. Roy DeCarava’s collaboration with writer Langston Hughes wasn’t published until 1955.

It was followed by a full ten year lull.

The next major black monograph was the South African exile Ernest Cole’s critically acclaimed House of Bondage (1967). (As I write from the African metropolis of Johannesburg, a city materially and metafictionally bound to Harlem, as exemplified by a history of correspondence between Langston Hughes and Drum writers such as Bloke Modisane, Lewis Nkosi and Zeke Mphahlele, it strikes me that history has no coincidences.) DeCarava and Hughes’s foundational visual text cleared the way for Cole’s House, and Cole made it possible for us to be having this discussion about Kwame Brathwaite’s blacks: They might have been in bondage in South Africa, but as we see the beauty in us, by extension we see it in them too. A year after House of Bondage was released in the US (it was immediately banned in Cole’s native country), the Black Consciousness movement reared its head in South Africa, community-organised, and espousing Brathwaite’s ‘black is beautiful’. And so the Black Atlantic brings us full circle, once again.

6.

On more than one occasion in the book Brathwaite makes sure to mention, on his travels and among his subjects, the impact of the Southern African (Namibian and Azanian) liberation projects on him as a Pan-African artist. He acknowledges Nelson Mandela’s 1994 inauguration as the completion of a black global struggle in the twentieth century Colonial Empire and Cold War framework, yet is quick to caution: ‘A luta continua, a vitória é certa—the struggle continues, victory is certain.’ Figures such as Sam Nujoma, Bob Marley and Ahmed Sékou Touré (none of whom are infallible struggle icons, thus perhaps then passionate and human) are boldly footnoted as photo-collaborators as well as foundational influences in the same Black Global Continuum as Charlie Parker, Beverly Johnson, Stevie Wonder and the Somali model Iman. At play here, at least ideo-logically, is Brathwaite expanding and extending our understanding and appreciation of the Black Atlantic philosophical-historical project as a global African project, including the often omitted Central and Southern African contribution to ‘civilising’ the world.

Through his archive (not entirely exhausted here) and in this book, Brathwaite’s art and his beautiful black people are but the latest in a fragmentary but never isolated lineage of Black Genius. ‘Tis not a surprise that his fellow Barbadian, rebel-cum-establishment-star Rihanna, has based her entire summer 2019 fashion range on Black Is Beautiful, the physical book.

Deborah Willis spoke about ‘communities’. It may seem, then, that as a technology and art form, books live with us in deed: via words and transmitted images with a profound understanding of their communities. (And not just their lovers.)

The best of them speak African, too.

- Bongani Madondo writes on poetry, photography and politics. He is Contributing Editor at the Johannesburg Review of Books. Follow him on Twitter.

Notes

The author would like to acknowledge Tina Campt’s Listening to Images (2017) for theoretical inspiration.

Thanks to left-wing author, thinker and friend Hein Marais for a conversation with the author on Painting as Music, 2010.

Full disclosure: Madondo also writes on African Photography for Aperture magazine.