Kenyan author and activist Binyavanga Wainaina has died, at the age of forty-eight.

Wainaina passed away at 10 pm on Tuesday night at Aga Khan Hospital in Nairobi after a stroke, a family friend has confirmed to The JRB.

Wainaina was born in Nakuru, Kenya, in 1971, and studied commerce at the University of Transkei in South Africa from 1991. He moved to Cape Town in 1996, where he worked as a travel and food writer and professional cook.

In 2002, he won the Caine Prize for African Writing, for his short story ‘Discovering Home’.

Wainaina was the founding editor of Kwani?, a journal of experimental writing, which he established in 2003, and which became an important and vital source for new African writing. He completed an MPhil in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia in 2010.

Wainaina was the founding editor of Kwani?, a journal of experimental writing, which he established in 2003, and which became an important and vital source for new African writing. He completed an MPhil in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia in 2010.

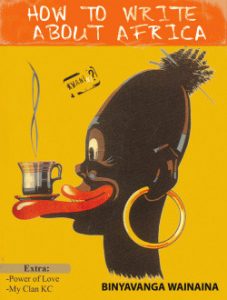

In 2012, his satirical essay ‘How to Write About Africa’, published in Granta magazine, attracted wide attention, and in 2012 he published a memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place, to great acclaim.

In 2014, at a time when many African governments were condemning and legislating against homosexuality, Wainaina defiantly came out as gay by publishing a ‘lost chapter’ of his memoir, in which he imagined a conversation with his late mother, titled ‘I am a homosexual, Mum’. In a subsequent talk at TEDxEuston, titled ‘Conversations with Baba’, Wainaina shared the exchange he would have liked to have had with his father before he died, concluding:

‘We cannot think of our continent as a hostile place. Too many of us have learnt to fear it. And I feel that if you trust it, engage with it and be involved with it in conversations of building, as adventurers, that this continent will start to sing to us again.’

Shortly afterwards was named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People.

Wainaina was no stranger to controversy, and in 2014 publicly criticised the Caine Prize and those who prioritise it over African initiatives, tweeting: ‘Dear Caine Prize, u made nothing, produced nothing, distributed nothing. U give a Prize of cash money a nd publicity. That is it.

‘Our continent is ripe, dangerous and renegotiating everything, do not sell your literature for small scholarships. It is a season of mad beautiful ideas, not safe career bum lickings.’ [sic]

In April 2015, Wainaina responded to the xenophobic violence in South Africa, in which at least seven people lost their lives, with a series of tweets describing his fond memories of the country in the heady political days of the 1990s.

‘I became an African in South Africa,’ he wrote. ‘They taught me to understand the possibilities of engaged political action. I was adopted by many.

‘So many black South Africans opened doors 4 me, and I was completely stranded and afraid. Never asked for anything in return. For years.

‘I have felt alone, really alone, many times. I never felt alone in a black university in South Africa.

‘To this day, there is a Xhosa in my heart somewhere deep.’

Wainaina visited South Africa in June 2015 to deliver a public lecture entitled ‘Being African in the World’ for the Department of Arts and Culture’s Africa Month celebrations. In the talk, he spoke about the transitional period he believed Africa is existing in as one of ‘anarchy or libertarianism’, adding that the youth will ‘define the fate of everyone’, as they have ‘signed out of the contract’ they had with the middle class and colonial rulers’:

‘Africa is taking its own shape. The youth bulge is enormous, and they stopped waiting. And so, they are going to make Nollywood, or they are going to make Boko Haram, and you are not even in that conversation. The States are not in that conversation.

‘It’s now no longer a question of saving them, to come and bring them to learn English and become I-don’t-know-what and give them income generation … they have gone. It’s not even, any more, a question of a lost generation.’

The author’s health began to deteriorate in November 2015, when he suffered a series of minor strokes. His friends and fans rallied and a huge fundraising drive was established to enable him to seek treatment in India. As a result of his illness, his speech became somewhat impaired and his voice tired during conversation. In 2016, on World Aids Day, Wainaina announced on Twitter that he was HIV-positive, tweeting, ‘i am HiV Positive, and happy’. [sic]

Listening to @BinyavangaW at Wits. Talk opens with a special message from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (keep an eye on @JoburgReview for that) pic.twitter.com/4sl8j4yBy4

— Jennifer Malec (@projectjennifer) July 25, 2017

In 2017, Wainaina visited South Africa again, and at an event titled ‘How to Write About Everything’ he spoke movingly about coming out, his writing, and how he was becoming his ‘true self’. Referring to his memoir, the writing of which was interrupted by violent political protests in Kenya in 2007, Wainaina pointed out how for African writers the personal and the political have a tendency to collide, saying:

‘I put my heart out there, not anything else, not my ego, I put my heart out there in my memoir. I think that that is the way I like to live, and that is the kind of writer I want to be.’

View some portraits of Wainaina, taken by The JRB Photo Editor Victor Dlamini:

Binyavanga WainainaA Victor Dlamini retrospective: https://johannesburgreviewofbooks.com/2017/09/04/the-literary-portraits-of-victor-dlamini-a-ten-year-retrospective/

Posted by The Johannesburg Review of Books on Monday, September 4, 2017

We met once in Kaduna, Nigeria and he was a fiery character.

He spoke fearlessly and is a model for the new narratives on Africa.

Rest in total peace Binyavanga. You were my very humble and polite boss when I worked for you at Kileleshwa( ur residence then).Shine on ur way.