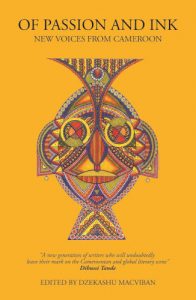

The JRB presents an excerpt from Of Passion and Ink: New Voices from Cameroon, a collection of short stories forthcoming from Bakwa Books.

Of Passion and Ink: New Voices from Cameroon

Of Passion and Ink: New Voices from Cameroon

Edited by Dzekashu MacViban

Bakwa Books, 2019

The excerpt is taken from a short story by A Bouna Guazong, translated from the French by Hannah Jakobsen. Of Passion and Ink, which is the debut publication from Bakwa Books, will be published in May 2019.

~~~

Brrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr!

Bam! The back door of the taxi slammed shut. Taking off like Usain Bolt, Champion set off on the tortuous two-hundred-metre path that separates the pavement from his home in the swamp at the bottom of the hill.

‘Sir, your money! Sir …’ The driver yelled in vain after looking left and right. Champion had already vanished into Obili’s ghetto. Barely fifty metres in, he turned to acrobatics to dodge a motorcycle taxi. For once that day, God was on his side. But some fifty metres farther, he found himself lying motionless in a stranger’s living room, having entered not through the door or window. He had crashed through the old, wooden wall, propelled like one of Van Helsing’s arrows by the collision with another motorcycle taxi. This time, God was distracted, as He had been since the morning of that Wednesday in April. As passers-by yelled and rushed over, the young man stayed unmoving, his eyes wide open. Then, blood slowly began to drip from his ears, mouth, and nose. The young Kulu Ybaning, a twenty-six-year-old graduate with a BSc in chemistry, unemployed full-time, and more commonly known as Champion, flew his white flag. He had lost the war of life. The train of his dreams and ambitions had just pulled into its ultimate station.

It was a Wednesday evening in April. Champion left the Ministry of Public Service in a rush and completely disoriented. For the past eight months, he had frequented their Human Resources department to inquire about the application he had submitted two years earlier. He hadn’t submitted the application because the Ministry was doing a recruitment, but rather for the simple reason that the director of the Ministry’s HR department lived not far from his neighbourhood. The paths of the two men had crossed multiple times, one always in his BMW, the other always on the heel-toe express. However, the first and only time they met face-to-face, things didn’t go the way Champion had planned.

The events that follow are not recounted in real time, talk less of chronological order, but it all started with his graduation from high school.

Up to his graduation, Kulu Ybaning did not have a nickname. Then, in the university, as he experienced the social realities of Kamer, Kulu ended up going by the moniker ‘Champion’. He chose this nickname simply because he believed that a name bore influence on personality especially as his names, which literally meant ‘poor tortoise’ when combined, weren’t bringing him any luck. He therefore thought it fair to take on a well-boding nickname to triumph over life, one that could boost him into action whenever he looked at himself in the mirror: Champion. He had opted for ‘Champion’ because he wished to be one. Having been born into a poor family, into destitution, to make it in Kamer, he had to be a champion. Besides, nicknames were a common phenomenon; the official name of the country itself was not Kamer, neither was the official name of the political capital, where he lived, Ongola. In fact, he lived in a country where reality was akin to fiction, a film straight out of Hollywood.

He was barely one point eight meters tall, a handsome and elegant young man who tried, as much as his limited resources could allow, to dress as stylishly as his contemporaries did. Financially speaking, he was not of the middle class but way below it. In short, he was a young bachelor without children, unemployed, with no prospects for the future. He was the son of a poor man in a country where social status tended to be hereditary; the sons of the unemployed were unemployed, the sons of ministers ended up becoming ministers. To make things worse, Champion was a two-time orphan: to his father and his mother. His father had died one Wednesday in April when Champion was nine years old, after a brief, scientifically inexplicable illness. His mother, for her part, died when he was twenty years old, on another Wednesday in April. She had been diagnosed with a benign tumour, but the operation went south. This type of thing was normal in hospitals in Kamer, where patients receive prognoses in the place of diagnoses. And when, by chance, the diagnosis is correct, you’re still not off the hook, because instead of surgeons we have butchers.

Thus, as both of his parents had died on a Wednesday, Champion had a particular relationship with Wednesdays, especially those in April. The only good thing ever to have occurred in his life on a Wednesday was his degree—he received it on a Wednesday, after six years in the Faculty of Science at the University of Yaounde I. And that was the same Wednesday he learned that he wouldn’t be able to continue his studies, because a new University regulation had been put out. The regulation, enacted for the sole purpose of expelling from the university those students who were frustrated by the system and thus more likely to rebel, stipulated the following: Any student who has taken longer than four years to complete a Bachelor’s degree should kindly turn to a private university to prove their mettle (if any) as students. Therefore, on the very Wednesday that Champion became a graduate in Chemical Sciences, he joined the ranks of the unemployed, full time. In fact, private universities were too expensive for poor parents, therefore out of the reach of HIPOs: Heavily-Indebted Poor Orphans. With this new status, Champion lived his life peacefully, busying himself with the search for a job to solve his problems. And problems, he certainly had plenty of. Little did he know there were more to come.

Of all the illnesses the Good Lord invited on Earth to upset the calm that comes with being in good health, diarrhoea deserves a place of honour. The problem that comes along with diarrhoea is that you’re forced to rush to the restroom whether you want to or not, whenever the malady decides. But, in contrast to HIV, to tuberculosis, to a cough, and to anything else, diarrhoea comes with a virtue as well: courage. Truly! He who is afflicted with diarrhoea is afraid of nothing. Ongola, the capital of Kamer, is a city where insecurity is a reality. Past a certain hour, it’s best not to venture outdoors, even on one’s own veranda! And especially in ghettos like Obili’s, where Champion lived. Whereas two Wednesdays of this month of April had gone by since Champion started spending almost every night on his veranda. Where was he getting this courage from? From a case of chronic and rebellious diarrhoea, considering that the hostel’s toilet was not in his room but at the end of the building.

A proverb has it that it is during your wife’s first pregnancy that you miss bachelorhood. After putting on in his Sunday best, Champion decided to stop by his girlfriend’s house, so that he might prove to her, if it were still necessary to do so, that he wasn’t deaf to her complaints and that he was struggling to better their lives. Eh! That Wednesday, he judged it preferable to go directly to see his girlfriend for the bickering—instead of calling and getting scolded over the phone—so that he could gain some time. Besides, he couldn’t call because his neighbourhood had not had power for two days and his phone was holding on to not more than one bar of battery.

As he could not make a phone call and risk completely depleting his battery, potentially missing a call from the Ministry, it was naturally more sensible to make the trip and be lectured in person by his girlfriend, without a telecoms operator acting as intermediary. However, in the end, he realized that it would have been better to call her and deplete his battery. By the time he was leaving his girlfriend’s place, Champion wasn’t heading to the Ministry simply because he wanted a job. He was now heading there in pursuit of a means to cause his girlfriend to hurt, a means to revenge. It is a feeling that is common in love relationships, seeking revenge on one’s partner after being jilted, when one still feels for the said partner. While men try to find a woman who is prettier and smarter than their ex, a woman tends to seek a man who is richer than their ex, or even hope that her ex doesn’t become successful, so that she won’t regret anything. So, Champion was now heading to the ministry to find a job that would give him a high status, the type of social status that makes some women dream. Yet! For the record, Champion had not left his girlfriend’s place in that state of mind because she had left him, no—she was nine months pregnant. It was worse. Not only had she left him, but she had also announced that, just after the childbirth, she would be getting married … to someone else. He therefore thought that if he became a civil servant at the ministry, she would regret dumping him.

~~~

About the book

These stories are the narrative footprint of a new generation of Cameroon writers … astonishing and delightfully creative.

—Billy KahoraAn intense, effervescent and unsettling tour of our cosmopolitan continent, doing what African writing does best—showcasing powerful, satisfying imagery in settings we think we know.

—Diane AwerbuckA new generation of writers who will undoubtedly leave their mark on the Cameroonian and global literary scene.

—Dibussi Tande

From Limbe, the seaside city, to Kolofata in the north of Cameroon, Of Passion and Ink moves from stories of star-crossed lovers, mental health, dark fantasy, displacement and speculative futures to radicalisation. These stories subvert what the Cameroonian short story is believed to be and offer exciting new directions.

Selected from the Bakwa Magazine Short Story Competition as well as commissioned, these stories herald new voices in Cameroonian fiction, by young writers who write in English and French.

Stories by: Dipita Kwa, Bengono Essola Edouard, Monique Kwachou, Dzekashu MacViban, Howard M-B Maximus, Nkiacha Atemnkeng, A Bouna Guazong, Rita Bakop, Momo Bertrand and Wise Nzikie Ngasa.

About the author

Amadou Bouna Guazong, a scriptwriter, comedian and audiovisual post-producer, holds a Master’s degree in performing arts and cinematography with a specialisation in film and TV production obtained at the University of Yaounde I. In 2010, he won the Grand prix Pabe Mongo in the Le camroes international writing contest. In 2014, he emerged as winner of the Naples raconte short story contest organised by the University of Naples in Italy, which published his short story, Le ‘chacal’, in the anthology of the contest in 2015. In 2016, with his short story, ‘Brrrrrrrrr!’, he was a finalist in the Bakwa Magazine Short Story Competition, which was open to Cameroonian writers all over the world. In 2018, he was a finalist in the Prix des inédits d’Afrique et outre-mer playwriting contest with his play, En route …

About the translator

Hannah Jakobsen is the Editorial Director of Phoneme Media, a nonprofit publisher of books in translation. She is also a translator and educator, and is based in Los Angeles, California.