As part of our January Conversation Issue, we present an excerpted interview from a new collection of Zoë Wicomb’s writing, Race, Nation, Translation.

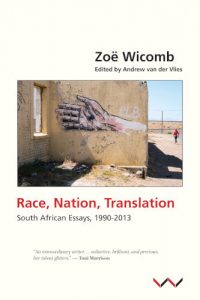

Race, Nation, Translation: South African Essays, 1990-2013

Race, Nation, Translation: South African Essays, 1990-2013

Zoë Wicomb (author), Andrew van der Vlies (editor)

Wits Press 2018

Andrew van der Vlies: Some might say that your early essays, and here I’m thinking in particular of ‘To Hear the Variety of Discourses’ and ‘Motherhood and the Surrogate Reader’ (though it’s clear, too, in ‘The Path from National to Official Culture’), display the insights of what we would now call intersectionality. Could you say something about how and when, and with what theoretical inspirations (to which you came where), your insights about the necessary imbrication of feminism and critical race studies took shape?

Zoë Wicomb: Intersectionality seems so blindingly obvious a notion, but the formalisation of such ideas is useful. Its underlying insights had of course been around for some time, notably through African American theorising of race and gender, and for me Angela Davis’s Women, Race, and Class (1981) was an eye-opener. Then there are bell hooks, Patricia Hill Collins, the fictional works of Toni Morrison, also Gayatri Spivak and others. I had not read Kimberlé Crenshaw at the time.

In the nineteen-eighties there was so much exciting scholarship I had to catch up on: Edward Said’s Orientalism and Johannes Fabian’s Time and the Other, to name a couple. If colonial discourse or othering, as they show, is linguistically incribed and has common features, then it seemed necessary to look at the ways in which sexism too could be theorised, and to examine the intersection of race and gender. It is the case that the various turns taken by critical studies—to language, ethics, and so on—invariably pointed to the imbrication of various social inequities. So, it was impossible not to be shaped by these insights.

Andrew van der Vlies: In a conversation with Homi Bhabha, John Comaroff reflected on postapartheid South Africa’s ‘heroic, hopeful effort,’ after 1994, ‘to build a modernist nation-state under postmodern postmortem conditions; at just the time, that is, when the contradictions of modernity were becoming inescapable.’ In ‘Shame and Identity,’ you observe that ongoing inequalities in postapartheid South Africa illustrate ‘the diverging interests of postmodernism and postcoloniality, or … may indicate the need to revise popular definitions of the latter to include the coexistence of oppositional and complicit forms.’ In your readings of the works of individual authors in Part 2 of this collection, you frequently make pragmatic use of Bhabha and others, too. I wonder if you would reflect on the ongoing tensions between postmodernism and postcoloniality in contemporary South Africa, either in relation to identity politics, or cultural production, or both.

Zoë Wicomb: Undoubtedly aspects of postmodernist thought are dismissable, such as the abandonment of enlightenment principles that remain of interest and relevance to postcolonial cultures, but I am reminded of Lewis Nkosi’s wry question of whether Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard is a postmodernist text that does not know its own name. He also asks how indigenous African-language literature can possibly be read without passing through the grid of the current postmodernism. Which is to point as Homi Bhabha does to the contradictions of modernity. If I refer to the postmodern effacement of history in coloured people’s denial of slavery, that has come full circle: the symbolic rainbow nation has run out of steam, and search for roots has unearthed coloured people’s slave heritage, indeed the more-indigenous-than-thou scramble for alterity flourishes among some coloured communities as a riposte to black nationalism. Having embraced the orthodox postcolonial position of valorising nationalism, South Africa has been saddled with that unwieldy monster. As I discussed elsewhere, the problem arises once the goal of liberation has been achieved when we see that the toxicity of nationalism spirals into its inherent xenophobia and intolerance of minorities that have been disguised by the notion of freedom. (Interesting here to chart the differences between South African and Scottish nationalisms.) Much of what I say has of course been superseded by Achille Mbembe’s incisive analysis of identity politics, its obsession with autochthony and difference, and its very development within a racist paradigm.

Andrew van der Vlies: Yes, you use that wonderfully critical formulation ‘scramble for alterity’ in your essay on recuperations of whiteness in postapartheid writing by a number of Afrikaans-language writers (Chapter 9).

Zoë Wicomb: I appreciate Kwame Appiah’s insistence that identity should be related to the ethical. I love his quotation of John Tomasi’s humorous dismissal of fetishised cultural membership, seen as ‘a primary good only in the same uninteresting sense as say, oxygen … It’s like form: you can’t not have it.’

Andrew van der Vlies: Yet the need for others and otherness is, you observe, at the heart of postmodern theory, which elevates otherness—in the guise of the minoritarian (in the work of Deleuze and Guattari, for instance)—to necessary metaphor, and yet (and this is a point you make in your engagement with Bhabha in the essay on shame and identity, too) because ‘otherness is clearly not a desirable condition for actual minorities, nor for the politically colonised who actively struggle for territory itself, it would seem that such an idealised view is essentially an albocentric, metropolitan one.’ Thus you hold to account the insights of any theory that is generative but comes up short against local conditions.

Could you say a little about your sense of the usefulness of theory in your own theoretical development (and, if I can push you, your own fiction)? Would you venture some thoughts about current debates about the need for ‘theory from the South’?

Zoë Wicomb: I’m reluctant to comment on my own work, but as I mentioned earlier, writing cannot be impervious to ideas or theories that occupy you at the time, much as you wouldn’t like to think of your fictional work as theory driven. It is fashionable to diss poststructuralism, and indeed I do in some of the essays question its usefulness, but at the time it was also immensely liberating. The very notion of decentring allowed one to question hegemonies, to escape orthodoxies and their strictures, so that the discovery that poststructuralism did not always chime with local conditions was itself thought provoking. And as you imply, such dissatisfaction has led to the need for theory from the South, a rejection of the West’s liberal universal, which in turn is also an aspect of decentering the dominance of the West.

South-south conversations are clearly a welcome change from the old one-way exchange, but by the same recognition of the incivility of the old model, one would like to think that it does not dismiss northern thought or exclude global exchange. As its theorists say, the North needs our input, but populist denigration of ‘Western knowledge’ that surfaced during the current student rebellion is alarming. In these early days discourses about theory from the South seem to be more about the need for it, rather than articulation of actual theories. If the South is as the Comaroffs claim a space of experimentation, I look forward to such experimentation, such revitalising knowledge production. There is an encouraging optimism about their idea of conversion from revolution to revelation and of social regeneration, but the proposed quest for wisdom and redemption is as yet hard to discern in South African political culture.

As far as I know, curriculum transformation has happened largely in Literary Studies. The worrying new appeal to ‘relevance’—current student protests are focused on difference, the uniqueness of their African identity, and that which they recognise or demand in a curriculum as relating to them—would suggest that transformation has not been as widespread as we imagined. Of course, the economy of scarcity, as Mbembe points out, impacts on subjectivity; however, while economic inequality fuels the student movement, the vast expanses of shantytowns, failure of education at primary level, and the fact that the majority of black students study at dysfunctional historically black universities in Limpopo, Venda, and Zululand are not the focus of the protests. Having said that, I do have some sympathy nowadays for students’ impatience with the status quo, their insistence on black identity in a culture that is as racially polarised as contemporary South Africa.

Nowadays legitimate disappointment and anger about ANC corruption and its loss of moral authority have somehow legitimated the idea of corruption-as-black, which via current South African media has become a recognisable discursive formation, while the term ‘white monopoly capital’ is routinely cited in scare quotes, presented as an absurd excuse for economic inequity. What is overlooked is the element of exchange that inheres in corruption. The independent Forbes List of billionaires in South Africa, published annually, shows a continuum of wealth from the apartheid regime. Inferable, then, that politicians line their pockets with lucre passed on by the already wealthy in return for lucrative state contracts that ensure continued wealth, but the reciprocity necessarily involved in money changing hands does not feature in the discourse of black corruption. The transaction of exchange is disregarded: the hands that give, in keeping with the category of whiteness, remain invisible. So theorising the South is no doubt a laudable project, but where the South is as racialised as South Africa is, we should perhaps start with learning to read our newspapers more carefully.

Andrew van der Vlies: Indeed. It seems to me, in fact, that we need the modes of reading and rereading you prescribe (and model) now more than ever. Allow me to turn (back) to the literary as space for reading. Your essays frequently deploy examples of cultural production from many media and genres, but you frequently turn back to the literary, including in these essays that we’ve chosen to group together as public-political interventions (or performances). Writers who feature here in particular include Sol Plaatje, Miriam Tlali, Njabulo Ndebele, and—preeminently—Bessie Head. Could you say something about where you first read each of these writers, and what it was about them that interested you? What in particular has Bessie Head meant to you, and why?

Zoë Wicomb: Yes, I was particularly interested in Bessie Head as the only coloured woman who, at the time that I tried to write, was a published author. Not surprisingly, I had not heard of Head until the early seventies when I came across Maru in the UK; but to my surprise I found that the Heinemann edition had a picture of me on its cover.

Andrew van der Vlies: Do you have any idea how that came to pass?

Zoë Wicomb: I later worked out that I had briefly met the photographer in a social situation at the time of publication, but I had no idea that he had taken the (unflattering) picture. Uncannily, and much as I hated the unauthorised use of the picture, I felt an affinity with her; Head’s novel gave me the courage or perhaps permission to write. While I find the homophobia in A Question of Power repulsive, her examination of race and exposure of African discrimination against the Masarwa is extraordinary for being explored within her commitment to Africa. She shows that it is not only possible but essential to be critical of that which you love and are part of. I am also moved by the ways in which she reworked her own tragic life story into fiction, so much more creative than the label of autobiography that critics invariably attach to black women’s writing.

Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi was not only the first African novel written in English, its publication history itself is significant. Edward Said’s injunction about the worldliness of texts as well as the importance of geography in the relationship between politics and culture take on a practical cast in relation to one of the more serendipitous effects of the 1976 Soweto rebellion. The Lovedale Missionary Press, fearful of student vandalism and believing that the rebellion would be confined to the North, moved their archives to Rhodes University in the Eastern Cape. In the process, the original typescript of Mhudi that Lovedale had earlier claimed to have lost, fell into the hands of Witwatersrand scholars Stephen Gray and Tim Couzens, who were at the time working on a reissue of the novel for the Heinemann African Writers Series. Previously dismissed by critics as a dull co-opted colonial offering, Mhudi turned out to have been severely bowdlerised, Lovedale Press having pressed the novel into a European realist mode. Thus Plaatje’s attempts at translation of traditional African forms into a Western novel by introducing a storyteller who passes on the history to a narrator, or by incorporating various elements of orality, including folktales, had been compromised. For me it was wonderful to be able to teach South African students about the translation of traditional forms and its contribution to theories of postcolonial hybridity.

Andrew van der Vlies: Moving on to those writers whose work you address in the essays we have grouped together as Part 2, could you comment on how you came to Coetzee and Vladislavić in particular? What has their work meant to you? And are there other writers from South Africa or elsewhere whose work has been particularly instructive or inspiring (or useful) for you in recent years?

Zoë Wicomb: White writing from South Africa was not hard to come by, so there were no obstacles to encountering these writers who are undoubtedly the most innovative, the most serious in exploring a new aesthetic for representing the South African crisis. How ingenious, Coetzee’s sidestepping the problem, for instance, of writing about a dispossessed black character as in Michael K, or Friday (of whom of course Lewis Nkosi had written earlier)! Coetzee was one of the first to look at settler culture, and through naming take responsibility for the colonial enterprise and its violence—all brave moves in the face of the various orthodoxies of the time.

While Ivan Vladislavić too is concerned with the ethical, it is his humour and irony that endure for me. Who would have thought that literary fiction could be a laugh-out-loud experience? In his latest collection of stories he also tackles the difficult issue of writing about atrocity, the torture and suffering that bring migrants to our shores. ‘The Reading’ gets around the problem through a narrative structure that includes narration by an English-language translator of the account of suffering. A story of horror is then embedded within another story of an event of its public reading, so that the taboo of horror and excessive feeling is shifted to the translator’s response. Central to Vladislavić’s story is an absence of the actual handwritten words by the subject of horror, the original writer who is present at the event. The embedded story then must remain incomplete in a number of ways. Another brilliant device for framing the horror is Vladislavić’s spotlighting of various members of the audience, their hilarious thoughts and activities, so that one thinks of Breughel’s Icarus, or rather, of Auden’s account of Breughel’s Icarus.

The topical issue of migration is represented very differently in Brian Chikwava’s extraordinary 2009 novel Harare North, a narrative about Zimbabwean migrants in the heterotopic city of London. Here nonstandard English and an intertext of Sam Selvon’s Lonely Londoners serve to revise the liberatory postcolonial project—now distinctly postlapsarian. Formally complex, and celebrating the rhetorical dimension of language, the novel explores the disturbing migrant life of its unreliable narrator whose identity eventually slips into that of his compatriot, an ‘original native’ who holds out against the deracination of ‘lapsed Africans.’ It is indeed humor and irony that steer this delicately managed writing of atrocity towards the ethical.

Andrew van der Vlies: Perhaps it’s worth noting that we had originally thought about including your wonderful essay on Chikwava’s novel in this collection but omitted it in order to retain a more tightly focused ‘South Africa’ focus. This is a strength, I think, but it might also of course be an indictment of a tendency to that old chestnut, South African exceptionalism. Do you find yourself turning away from South Africa in what you read or write, or does its pull continue to direct your work?

Zoë Wicomb: Yes, I’m disappointed that the Chikwava essay didn’t make it. Perhaps because I don’t live there, South Africa in terms of writing remains my focus, and nowadays with history seeming to repeat itself, writing is once more a way of dealing with the distress of my visits to the Cape. Certainly my reading is not limited to South Africa; that would be unnecessarily punitive and, well, unthinkable. But exceptionalism remains a problem. There is, for instance, within the country very little foreign news in the daily newspapers, and cousin to exceptionalism is xenophobia, as seen in the horrific violence of the poor against African immigrants.

Andrew van der Vlies: Let us leave our conversation there, with this version of the beggars at our doors that you invoke for us as an emblem of ongoing injustice. Your writing and your thinking, exemplified in these essays and in your generous responses to my questions, continue to model ethical returns to these dilemmas. Thank you, Zoë.

November 2016 and March 2017

Glasgow and London

~~~

About the book

This collection establishes Wicomb as a leading critical commentator on and scholar of South African national politics and its cultural forms. The essays are outstanding. They present the most incisive, challenging and dexterous interventions in the South African cultural field and ask the kinds of questions that cut to the quick of the issues at stake in them.

—Meg Samuelson, University of AdelaideGiven the complex nature of socio-political transition, most societies struggle to define their intellectual trajectory. In South Africa we are fortunate to have Zoë Wicomb’s unerring instinct to provide informed commentary and analysis of our literary landscape.

—Mandla Langa, author of Dare Not Linger

The most significant nonfiction writings of Zoë Wicomb, one of South Africa’s leading authors and intellectuals, are collected here for the first time in a single volume. This compilation features critical essays on the works of such prominent South African writers as Bessie Head, Nadine Gordimer, Njabulo Ndebele, and JM Coetzee, as well as writings on gender politics, race, identity, visual art, sexuality and a wide range of other cultural and political topics. Also included are a reflection on Nelson Mandela and a revealing interview with Wicomb.

In these essays, written between 1990 and 2013, Wicomb offers insight on her nation’s history, policies, and people. In a world in which nationalist rhetoric is on the rise and diversity and pluralism are the declared enemies of right-wing populist movements, her essays speak powerfully to a wide range of international issues.

About the authors

Zoë Wicomb is the author of You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town, David’s Story (winner of the M-Net prize), Playing in the Light and The One That Got Away. She is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Strathclyde and was an inaugural recipient of the Donald Windham-Sandy M Campbell Literature Prize. She lives in Glasgow.

Andrew van der Vlies is Professor of Contemporary Literature and Postcolonial Studies at Queen Mary University of London and Extraordinary Associate Professor at the University of the Western Cape.

One thought on “[Conversation Issue] ‘Intersectionality seems so blindingly obvious a notion’—Zoë Wicomb in conversation with Andrew van der Vlies, from their new book Race, Nation, Translation”