This year’s Annual Sol Plaatje Lecture was delivered on 17 October at Sol Plaatje University, Kimberley, by Professor Kole Omotoso. The JRB presents his remarks in full.

The Power of Politics, the Power of Literatures—Sol Plaatje and the Madness of Making Humanity Shudder

by Professor Kole Omotoso

Professor Kole Omotoso delivered the annual Sol Plaatje Lecture on Wednesday evening. Dr Brian Willan was the respondent. pic.twitter.com/ZaBH3T6REh

— Sabata-mpho Mokae (@mokaewriter) October 19, 2018

Prefatory quotations:

Retribution

[Native Life in South Africa by Sol Plaatje ends with this poem, first published in The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, USA, in August 2016.]

by Ida B. Luckie“Alas, My Country! Thou wilt have no need

Of enemy to bring thee to thy doom

If these be they on whom we must rely

To prove the right and honour of our arms.”Thus spake Abdullah, gazing, with sad eyes

And heart fear-stricken, on the motley horde

Of Turks now gathered in with feverish haste

To meet the dread, on-coming Bulgar host.

Truly he spake, for scarce the foes had met

When the wild fight began, the vengeful sword

Of the Bulgarian taking toll

Of fleeing thousands fall to rise no more.

Surely the years bring on fatal day

To that dark land, from whose unhallowed ground

The blood of countless innocents so long

Has cried to God, nor longer cries in vain.But not alone by war a nation falls.

Tho’ she be fair, serene as radiant morn,

Tho’ girt by seas, secure in armament,

Let her but spurn the Vision of the Cross;

Tread with contemptuous feet on its command

Of Mercy, Love and Human Brotherhood,

And she, some fateful day, shall have no need

Of enemy to bring her to the dust.

Someday, tho’ distant it may be – with God

A thousand years are but as yesterday –

The germs of hate, injustice, violence,

Shall eat the nation’s vitals. She shall see

Break forth the blood-red tide of anarchy,

Sweeping her plains, laying her cities low,

And bearing on its seething, crimson flood

The wreck of government, of home, and all

The nation’s pride, its splendour and its power;

On, with relentless flow, into the sea

Of God’s eternal vengeance wide and deep,

But for God’s grace! Oh, may it hold thee fast,

O’er wrong and o’er oppression’s cruel power,

And all that makes humanity mourn.

*

[November 1911]Shortly after returning to South Africa, Seme had drawn a loaded revolver on a group of whites who took violent exception to his decision to travel in the first-class compartment of a railway carriage (‘Like all solicitors,’ he subsequently explained, ‘I of course travel first class.’)

—from Sol Plaatje: A life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje 1876-1932 by Brian Willan, p. 229.

*

In directing his readers to the lessons of history Plaatje’s point was a straightforward one: unless tyranny and oppression were ended peaceably, it was inevitable that violence would remain the only alternative.

—Ibid, p 533.

*

‘Seek ye first the political Kingdom and all else shall be added unto you.’

—Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana, 1957 to 1966

~~~

From The End of Power by Moisés Naím: ‘The approach here is practical. The aim is to understand what it takes to get power, to keep it, and to lose it. This requires a working definition, and here is one: Power is the ability to direct or prevent the current or future actions of other groups and individuals. Or, put differently, Power is what we exercise over others that leads them to behave in ways they would not otherwise have behaved’ (p. 16).

The dream of politics is to achieve its aims no matter what it takes. The dream of literature is to achieve its aims through means that are humane. Yet, the same set of people have always been drawn to both politics and literature. It was the late Chief Bola Ige, then the Governor of Oyo State in South West of Nigeria, who said that politicians and writers have the same clients—the people. He was addressing the inaugural conference of the newly formed Association of Nigerian Authors at Obafemi Awolowo University in 1981. Both politicians and writers care for their people. Both would wish to do something—material, spiritual—something useful for their people.

Both politicians and writers sacrifice even their families in the process of caring for their people and in service to them. Perhaps these and other still unmentioned things draw writers to politicians and politicians to writers. In terms of achieving their aims, the politician does the impossible immediately while for the writer miracles take a little longer. The politician envies the writer’s longer-lasting achievements while the writer wished his writing could perform his or her desired miracle immediately.

There have been intriguing friendships between politicians and writers, such as the one between the Colombian writer and Nobel Laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez and the former Cuban President Fidel Castro. Nearer home we have the friendship between the Governor mentioned above and the Nigerian Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka.

Two other examples are worth noting. There was the friendship between Andre Malraux (1901 – 1976) and Charles de Gaulle (1890 – 1970), president of France from 1944 to 1946 and again from 1965 to 1969. The other writer-politician friendship to note is that between Gamal Abdul Nasser (1918 – 1970), president of Egypt from 1952 to 1970, and Mohamed Hassanein Heikal (1923 – 2016), editor of the authoritative Al-Ahram for 17 years, from 1957 to 1974.

Yet, there are few studies of the writer-politician fascination that I know of. The most famous would be Fidel & Gabo: A Portrait of the Legendary Friendship Between Fidel Castro and Gabriel García Márquez (2009) by Ángel Esteban and Stéphane Panichélli.

My conclusion, is that when it comes to the lure of power, art, all art, constitutes rituals hoping to achieve political miracles.

I wrote ‘The Ritual Dreams of Art’ as a young editor, years ago. Other than its title, nothing remained and there was nothing to remind me of its content until I met Sol Plaatje. I read and re-read his Native Life in South Africa, first published in 1916. Then I had to teach Mhudi, his 1930 novel that would set the mould for many African writers from outside of South Africa in the 1950s and 1960s. Amos Tutuola and Chinua Achebe would follow the path that he had beaten with his only published novel. Of course, I read his other writings in English including the diary of the siege of Mafeking and lots of journalism. The politician and the writer in Sol Plaatje got me looking for that short essay of long ago.

The search for that essay and for Sol Plaatje brought me to South Africa more than twenty-five years ago. To say that Sol Plaatje was a politician and a writer combined is saying nothing new. What might not be familiar is the idea that he viewed his political frustration at the hands of racist segregationists as merely a temporary delay in the achievement of a humane society in South Africa. Not only that: he then concentrates on his writing and used this writing to prophesy the future of his dreams.

So, my topic today, ‘The power of politics, the power of literatures: Sol Plaatje and the Madness of Making Humanity Shudder, acknowledges that it is in South Africa, more than any other African country, that both powers are best demonstrated. My topic also acknowledges the writers and the politicians who made it possible for me and my family to come to live in South Africa in February 1992.

I came to South Africa a year short of my fiftieth birthday, an age at which some people are preparing for retirement. Although I came to teach initially at the University of the Western Cape, I came as a student of African politics. I had been a student in Cairo, studying Arabic and the Arab theatre and cinema. I had been a student, if only for a short period of three months, at what later became the University of Dakar. I was familiar with both Arab Africa as well as French Africa. Coming to South Africa would complete my education in terms of the politics and literatures of Africa.

As an undergraduate student at the University of Ibadan I had met Zeke Mphahlele and read his Down Second Avenue, and read A Walk in the Night by Alex La Guma with whom I share one point. Both of us had been invited, at different times of course, to the late Soviet Union by the Soviet Writers Union and Progress Publishers of Moscow: him in 1978, me in 1983. Before then I had read Cry, the Beloved Country by Alan Paton as a secondary school text and recited the first page from memory to my classmates: There is a lovely road that runs from Ixopo into the hills. These hills are grass-covered and rolling, and they are lovely beyond the singing of it… But the rich green hills break down. They fall to the valley below, and falling, change their nature. For they grow red and bare; they cannot hold the rain and mist, and the streams are dry in the kloofs (p. 7).

I arrived as a student, a post-graduate student in South African politics and literatures. My teachers were Dr Frederick van Zyl Slabbert, sometime leader of the opposition in the apartheid parliament, Joe Mathews, son of Z K Mathews and father of Naledi Pandor, all political activists and writers. And among my writer teachers were Mandla Langa and Njabulo Ndebele. Others were Breyten Breytenbach and Antjie Krog. Others were Keotapetse Kgositsile and Wally Serote. No other country has more writer-politicians, politician-writers than South Africa. This, I think, is partly the reason why the salvation of both the oppressed and the oppressor became a major issue in the struggle for the liberation of South Africa. South African writer-politicians had set themselves the near-impossible task of liberating the oppressed as well as the oppressor.

It is not stated so blandly, the task of the African freedom fighters, to liberate the African oppressed and the European oppressors of the Africans. Rather, the freedom fighters diluted the purity of the struggle by admitting of the friends of the Africans, of friends of the oppressed, just as other freedom fighters had diluted their struggles at the beginning.

Towards the end of Mhudi, Sol Plaatje’s only historical novel, our author shows his disillusionment with this situation. The Barolong had joined the Boer to defeat the armies of Mzilikazi. In taking his people further north to a new settlement in Bulawayo, Mzilikazi curses the Barolong from generation to generation:

The Bechuana know not the story of Zuniga of old. Remember him, my people; he caught a lion’s whelp and thought that, if he fed it with the milk of his cows, he would in due course possess a useful mastiff to help him in hunting valuable specimens of wild beasts. The cub grew up, apparently tame and meek just like an ordinary puppy; but one day Zuniga came home and found, what? It had eaten his children, chewed up two of his wives, and in destroying it, he himself narrowly escaped being mauled … Chaka served us just as treacherously. Where is Chaka’s dynasty now? Extinguished, by the very Boers who poisoned my wives and are pursuing us today. The Bechuana are fools to think that these unnatural Kiwas [whites] will return their so-called friendship with honest friendship … [for] when the Kiwas rob them of their cattle, their children and their lands, they will weep their eyes out of their sockets and get left with their empty throats to squeal in vain for mercy.

In Saint-Domingue, where the slaves were fighting their enslavers, the French, they admitted the help of ‘les amis des Noirs’—friends of the Blacks. But this was only at the beginning. Once it became obvious that Napoleon and his money bags were bent on restoring slavery to the island, it was a fight to finish, a finish that would make humanity shudder.

In January 1804, the leadership of the slave army ordered that every white person—child, woman, man, aged—must be killed. Every white person was killed and the new Haitian constitution decreed that no white person may ever land on Haiti, at the pain of death. That horrendous crime did make Humanity shudder. So much for depending on the friends of the oppressed.

The South African freedom fighter, besides accepting the role of the friends of the oppressed from among the oppressors, tried to make the oppressor realise the futility of segregation and apartheid. It would never work. It would not be manageable. That was the first thing. The second thing was the need to be aware of what was called ‘the revenge of the oppressed’ on the oppressor, such as took place in Haiti that made Humanity shudder. Un jour viendra—A day is coming when the servant becomes the master and the master becomes worse than the servant.

Things were much much simpler in the rest of Africa. There were the colonisers and there were the colonised. The freedom fighters here had to free the colonised and God help the coloniser, who can get lost as far as the liberated ex-colonised Africans were concerned. And invariably, the coloniser had somewhere to go: he could go back to the mother country, or else he could go to Australia, another colony, still to be decolonised.

In the case of South Africa, the Boer had no European home to return to even if he wanted to go back. More than three hundred years and thousands of miles separated him from his seventeenth-century family.

The South African Native National Congress (SANNC), later the African National Congress, was formed in 1912, benefactor of other earlier attempts. Between 1913 and 1948, the Afrikaners perfected their initial hesitant segregationist policy into their bold apartheid system. They took land, they took security, they took education, they took even initiative from the African, all expressed in the most cynical English: ‘Natives Land Act’ took land from the natives; ‘Native Labour Regulation’ tightened the process of how the whites controlled and deployed the labour of the natives; the ‘Mines and Works Act’ reserved some categories of work on the mines to whites; the ‘Dutch Reformed Church Act’ prohibited Africans from being full members of that church; and the ‘Union of South Africa’ united the Boers with the Britons against the Bantu! Before then, the ‘Peace of Vereeniging’, which ended the Anglo-Boer War (later named the South African War) in 1902 marked the commencement of segregation and separate development. This was organised prejudice, inherently dangerous and violent.

The liberal political system in the Cape, which Sol Plaatje hoped would be extended to the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, was wiped out, wiping out the hopes of Africans of some means. Next followed the courts. They were made to bow to the wishes of the whites. From this time onwards, it was clear to the politician-writer that the struggle as previously made was over.

During the Anglo-Boer War, both the British and the Boer had refused to let any of the natives allied to them, in the war, have access to firearms. It was obvious to both the Boer and the Briton that the way things were going in South Africa, the Bantu would still fight the combined forces of the Briton and the Boer. So, why would they arm the natives?

Sol Plaatje was the first General Secretary of the SANNC and for the next four to five years he worked assiduously, without any payment, for the Congress. When in 1917 he was offered the presidency of the SANNC, now renamed the African National Congress, he rejected the offer. The reasons given for Plaatje’s refusal were: the need to attend to the well-being of his family and the necessity of re-establishing his newspaper business along with his writing profession.

I would suggest that there was a third reason. Plaatje had followed the writings and the reasonings of John Tengo Jabavu, editor of Imvo. In its issue of 23 April, responding to a hostile editorial in the Bloemfontein Express, Jabavu warned of the dire consequences of the continued oppression by Boers of Africans living in Transvaal, and predicted that in the event of war between the Transvaal and the British imperial government the African tribes of Transvaal, ‘on whose neck the foot of the oppressor has been pressing with inhuman severity, would rise for revenge and a scene might ensue which would make humanity shudder, but which must be expected when a host of conquered savages finds an opportunity to burst its bonds’.

Plaatje never forgot the phrase about making humanity shudder. Here, we must not forget that John Tengo Jabavu was one of a few Africans who did not see anything particularly wrong with the Natives Land Act. He was compromised, can we say captured, by white financial support. For such a mistake, he was punished severely by his people, the Africans.

Having exhausted all the possible actions to stop the creeping policy of segregation and apartheid, both at home and in Britain, Plaatje knew the struggle would need to take a new format. He also felt that it should not be by the way of making ‘humanity shudder’, as was to happen in the workers’s paradise that had been declared in Russia in October 1917. It is to be noted that the socialist International had said in its issue of 8 June 1917 that ‘the natives are exploited and oppressed not really as a race, but especially as workers’. To accept the leadership of the Congress was either to continue the path that had led to failure—that is: appealing to the humanity of the oppressors—or to change the tactics of the struggle completely, through the path of danger and violence.

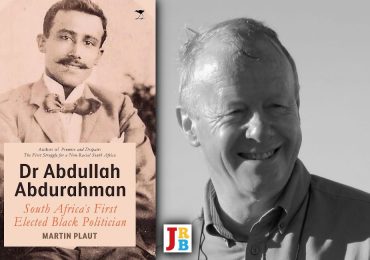

Plaatje quotes the speech of Dr. A. Abdulrahman, then leader of the African Political Organisation and member of the Cape provincial assembly, part of which must have chimed with his general feeling that the Afrikaner, along with the British, had abandoned the path of ‘political righteousness’ by organising prejudice as government. I quote: ‘The restraints of civilisation were flung aside, and the essentials of Christian precepts ignored. The northward march of the Voortrekkers was a gigantic plundering raid’ (Native Life in South Africa, p. 133).

Talking of ‘appeal-weariness’, Sol Plaatje says: ‘The time will come when these leaders will tire of spending their own money in paying fares to the Government Railways, to render free services to a government which taxes them to pay other people lavishly for similar work, while it does not even tender them so much as a word of thanks’ (p. 207). Further down that same page, Plaatje says: ‘These cruelties [caused by the Native Land Act] are euphemistically described as the first step towards the segregation of white and black, but they might more truthfully be styled the first steps towards the extermination of the blacks.’

Obviously, pleading humanity to people who want to exterminate you is not the right or sane action to take as response.

British newspapers, as well as members of both British Houses of Parliament, are quoted in full in Native Life in South Africa to show that the black protesters were at the end of their constitutional options. Here is Mr. Dower, described as the secretary for Native Affairs: the African ‘must sell his stock and go into service … It is time that parliament gave some attention to its obligation in regard to the South African native. He has no vote and no friends—only his labour, which the white man wants on the cheapest terms. And the white man has got this by taking his land and imposing on him taxes that he cannot pay. In fact, the black man is “rounded up” on every side, and if, as the deputation suggests may be the case, he is forced to acts of violence, it will not be possible to say that he has not had abundant provocation’ (p. 213).

One of the British newspapers wondered at the inability of the British Empire’s parliament to override the South African parliament in terms of the Natives Land Act, and asked, if that parliament were to legislate the restoration of slavery in that part of the British Empire, would the mother of parliament keep quiet? ‘It is surely impossible to admit that Great Britain can do nothing for the mass of the native population, although at the moment it appears to them that though they are subjects of the King he cannot even hear their appeal, and will do nothing for them, and has abandoned them, a state of affairs which is quite incomprehensible to them and leads them to depend solely on themselves to obtain redress—and that way rebellion lies’ (p. 217).

Yet, Sol Plaatje was too much of a struggle artiste to know that the time was not ripe. The military option was not available then. Those who took on the leadership could do nothing until the 1950s and 1960s.

The Yoruba African culture cautions each family and each people to look after their mad men and mad women because of the day they would have to face the mad men and the mad women of other families and other peoples. Only the mad men and mad women of Haiti could have ordered the slaughtering of all white men and women, children and aged that January more than 200 years ago. At the same time, it is the mad men and the mad women of the Boers who insisted on complete apartheid and a separate development that saw white people controlling the possibilities and destinies of the Africans. If for now the mad men and the mad women of the Africans have not emerged, it is because of the writer-politicians who would rather save both the oppressor and the oppressed in South Africa.

As Thomas Sankara, head of State of Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987, would say:

You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain amount of madness. In this case, it comes from nonconformity, the courage to turn your back on the old formulas, the courage to invent the future. It took the madmen of yesterday for us to be able to act with extreme clarity today. I want to be one of those madmen.

He was killed by his bosom friend Campaore.

Writers might be inspired and be possessed but they are not mad enough to do away with HUMANENESS. Sol Plaatje loved his people. In fact, one of his biographies is entitled Lover of His People. This one was written by Setsele Modari Molema.

Politics needs and uses money, arms and populations. Invariably the oppressor controls all three. To participate in politics and liberate herself/himself, the oppressed must acquire these. Oppressors monopolise the means of acquiring money, arms and people. They do everything imaginable and unthinkable to prevent the oppressed from acquiring money, arms and people. They divide Africans into tribes, ethnic groups, language differences, racial identities, gender isolations and sexual orientation.

Literatures have Truth, Justice and Charity. What literature says is verifiable by all. It ensures that the weak are not oppressed and all are equal before the law. It treats all human beings with kindness and tolerance. No wonder politics’s effect is said to be ‘hard power’ while literatures’s is ‘soft power’. Politics’s effect is immediate. Literatures’s effect is indeed, a long walk to freedom.

The First World War came in 1914 and lasted until 1918. It provided another opportunity for the Congress to help the British Empire defeat Germany, with the promise of freedom in South Africa come the end of the war. The Congress even sent delegates to Paris to present the case of the natives to the peacemakers of Europe. By now the British had come to agree with the Boer that the natives must be kept in their place with the help of segregation and, later, apartheid. Every appeal made for the British Parliament to override the South African Parliament was rejected. Members of the Congress delegation returned to South Africa—with the exception of Sol Plaatje. He stayed in London to see if he could sway the opinion of the British public to make their government make the South African government change its policy of segregation and separate development. He failed.

In the introduction to the American edition of Native Life in South Africa published in 1998, Neil Parsons of the University of Botswana, says:

Plaatje returned home to Kimberley to find the SANNC a spent force, overtaken by more radical forces … Plaatje became a lone voice for old black liberalism. He turned from politics and devoted the rest of his life to literature (Loc 126).

So, Sol Plaatje then concentrated on Literature. He spent his energy on his work on Tswana language issues and the translations of the plays of William Shakespeare. But he won’t let us forget the following poem by Haki R. Madhubuti, born Don Lee, African-American poet and publisher:

i ain’t seen no poems stop a .38,

i ain’t seen no stanzas break a honkie’s head.

i ain’t seen no metaphors stop a tank,

i ain’t seen no words kill

& if the word was mightier than the sword

pushkin wouldn’t be fertilising russian soil

& until my similes can protect me from a nightstick

i guess i’ll keep my razor

& buy me some more bullets.

Thank you.

- Professor Kole Omotoso is Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Elizade University, Ilara Mokin, Ondo State, South West Nigeria