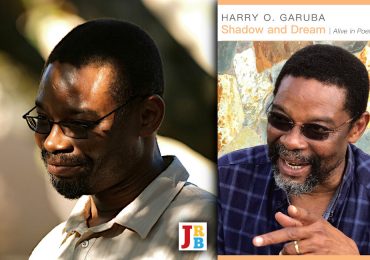

Sanya Osha remembers the late Harry Garuba, who died earlier this year.

Since he passed in February this year, friends of Harry Garuba around the world have expressed their deep sense of loss in many tangible ways. A professor from the University of Cape Town, where Harry worked, is editing a book of tributes in his honour. Another academic working out of the University of South Africa in Pretoria is doing something similar. Amatoritsero Ede, a Canada-based poet and editor, is dedicating an issue of Maple Tree Literary Supplement solely to celebrating Harry’s life and work. At the University of Ibadan, his alma mater, there have been webinars, poetry and essays honouring him. The outpouring of grief, loss and celebration has been simply immense—the latter in recognition of what he was able to accomplish during his life and the large number of people he touched and transformed.

As a young academic, Harry was much in demand, his expertise constantly being sought out by much older professors, who wanted him as a contributor to their projects. While his peers were struggling, practically begging, to be published, the contrary was true for Harry. He almost couldn’t keep up with the pace of the opportunities being thrown his way. He was a frequently invited guest lecturer at the United States Information Service in Ibadan, sadly now defunct but then a major intellectual and cultural hub, especially under then stewardship of Deji Haastrup.

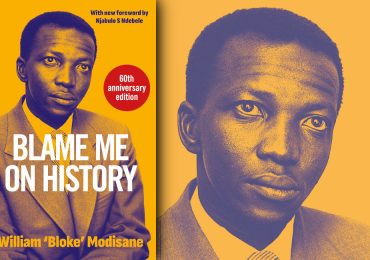

At the age of twenty-four, Harry published Shadow and Dream and Other Poems, a volume that quickly gained a cult following with those who came to be known as the ‘Third Generation’ of modern Nigerian writers—that is, the generation after the likes of Femi Osofisan, Kole Omotoso, Festus Iyayi, Odia Ofeimun and Tanure Ojaide.

Harry’s slim collection of verse is particularly distinctive for its controlled pursuit of symmetry, be it as a purely aesthetic preoccupation or as an emotional revelation. It is a cannily successful exploration of the notion of balance in its various forms, that is, the balance to be found in natural beauty or the balance to be found in artistic perfection. Indeed, it seemed to imply there was balance to be found in almost everything. At the time, it wasn’t possible to discern whether Harry’s interrogation of balance and symmetry was a reflection of his inner constitution or an idea he chanced upon. With hindsight, the former view seems to be the case. In his life, Harry always seemed to pursue balance in multiple, interconnected relationships. He also seemed to think there was a ceaseless dialectic of connectedness working all the time, binding us all together in innumerable and inexplicable ways.

I remember reading one of Harry’s academic essays in the early nineteen-nineties—published in an obscure local journal the name of which escapes me—and noticing the same dimension of symmetry and proclivity for tonal and textural balance. Uncharacteristically, it appeared in an issue on the theme of democracy and not literature per se. As with many literary scholars of the period, Harry had been compelled to venture into the arena of donor-funded research, and democracy and the democratisation process in Africa were fashionable topics of social science research. Harry’s eight-page contribution was well-written, moderately researched and almost mellifluous in tone and thematic arrangement. Structurally, every word just seemed to be in its right place.

Harry had been widely billed as the man most likely to launch Nigerian literature into its next phase, a future that promised groundbreaking artistic accomplishments and radical reappraisals. He had been pencilled in to be the lead horseman of such an exhilarating creative apocalypse. All his academic mentors unquestioningly acknowledged his undeniable potential. But it was his younger acolytes who were in fact his most ardent supporters, his availability and constant proximity to them being key elements of their high regard.

Daily, Harry held court at the student union buildings—notably not the university’s staff club—at Alhaji’s Bar or the quasi-subterranean tavern directly opposite known as Jibola’s Bar. Alhaji’s was bright, airy and full of space. Its atmosphere seemed to cleanse your soul if you had been having a bad day. Jibola’s Bar, on the other hand, was dark, claustrophobic and filled with cloistered breath, visceral odours and other barroom emissions, all bunched together like the forests of the delta. Apart from Jibola, the main barman, who was blessed with a beautiful soul, most of the other men who worked there were mean-spirited and prone to violence. One such temperamental barman was called Abuna, a rough-hewn curmudgeon who usually went about bare-chested, in order to be ready for the next fist fight. One evening it all got too much and he was doused with battery acid, which scalded parts of his face and chiselled chest. Not long afterwards, some benefactors ferried him to the United States to continue his life as a rough and ready minion.

Harry made it cool to want to become a poet and demonstrated that you didn’t have to be square to be a lecturer. Most evenings, when the day’s work was completed, he would be seated at a table surrounded by poets, based at the university or farther afield, such as the late Idzzia Ahmad and Emman Usman Shehu, both of whom ventured down from the north of the country, or Uche Nduka, a peripatetic figure, who dropped in without warning as if from nowhere, flashed his remarkable brilliance and promptly disappeared again. It wasn’t for nothing he was nicknamed Dambudzo, after Marechera, the mercurial Zimbabwean novelist.

During those memorable nights at Alhaji’s Bar, plied with endless gallons of beer, we would debate the niceties of Christopher Okigbo’s poetry or the captivating melancholy of Gabriel García Márquez’s lush novels, discussions topped with a collective admiration of Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction and Michel Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge. Harry was at the forefront of disseminating those cutting-edge discourses and theories, which made the conversational company all the more lively. When visiting scholars Ato Quayson (who was then based at Cambridge University) and Thane Maxwell, a fascinating Australian free spirit, found themselves in Ibadan, Harry was the go-to guy to dispense nuggets of rich cultural history relating to the cosmopolitan sector of the city.

Harry’s block of flats on Phillipson Road was ensconced within a thick forest of trees that ended in a cul-de-sac. His apartment itself was dark and quiet, being largely devoid of the noises made by radio and television. No place in the two-bedroomed dwelling was off limits to anyone, including first-time visitors. It was touching to watch Harry prepare steaming hot platters of omelettes for a bunch of poets nursing severe hangovers on a Sunday morning, even when he had probably had more to drink than anyone else. We all believed Harry would be around for a long time. Although not much about him announced it, he was built like an ox—he indisputably was. But as in all things, there was nothing overbearing about his stamina or powers of endurance. His varied and copious strengths were demonstrated in the manner in which he drove himself in his work, single-handedly managing his ever-growing and demanding web of intricate relationships and his undying quest for the pleasures of life, knowledge and experience.

Harry did once own a pristine-looking radio, which he would clutch and carry around his flat while preparing for yet another busy day. Wearing a pair of tracksuit pants underneath a loose-fitting white T-shirt, he would hold the device to his ear, feeding his ever-inquisitive mind with information from programmes like the BBC news, which he would then share with anyone who cared to listen later in the day. I recall his uncharacteristic reaction over the sordid affair of General Manuel Antonio Noriega, the Panamanian dictator who was desperately wanted by the United States government for a number of crimes, including drug trafficking. In his boyish voice, Harry argued that the dictator ought to be ‘dragged like a rat’ out of power and hurled before prosecution authorities. Such verbal vehemence was quite rare with him.

After a long night of revelry, involving poetry, song and sometimes dance, Harry would wake up in the morning chewing on a piece of stick, which he used as an endogenous toothbrush. He would furiously work at ridding his teeth of stubborn tobacco stains. Beads of sweat would appear on his forehead and all over his body, drenching his T-shirt. The exercise was obviously geared towards augmenting the gleam of his irresistible smile. All over the floor of his living room there would be a disheveled gaggle of wasted poets with musty, unwashed bodies, lying amid a disarray of dusty sandals, overflowing ashtrays, totemic literary books, dog-eared poetry notebooks, half-consumed bottles of liquor and battered rucksacks. It wasn’t unusual to find Harry gingerly stepping over sleeping bodies in various states of undress—never, however, complete undress—attempting, without uttering a single word of complaint, to bring a measure of order and domestic decency to the topsy-turvy scene. He would literally be cleaning up after everyone. That was just the kind of person he was.

As poets, we impatiently awaited free moments when we could read our tortured verse—usually penned for some elusive love interest—to the undisputed prince of poets. We loved to see Harry smile over a particular fragment he admired and never failed to be delighted when he repeated it during a conversation a few nights later. We made him the arbiter of good poetry and taste, and the expectations for him to create great art of his own mounted with each passing day.

But Harry merely retreated behind an inscrutable smile and rancid fumes of beer. His smile had always been a tad mysterious, slightly impish and often all-knowing. We entrusted him with the role of a benign Svengali, an ever-discreet and ostensibly detached Warholian umpire who watched with a sliver of bemusement the squabbles of ambitious self-opinionated poets and conniving wannabes. (He also attracted a lot of talentless hangers-on who simply stuck around to imbibe as much free beer as they could.)

The hacks were the ones clamouring the loudest for the prince to be made king, but if you asked them, king of what? They wouldn’t be able to tell you. Like everyone else, they were simply drawn in by Harry’s quiet, unobtrusive charisma. The poets, on the other hand, were attracted largely to his literary brilliance. Harry had read almost everything and possessed the most fascinating angles to every intellectual debate.

If there was one issue on which the poets and non-poets could agree, it was the matter of Harry’s unstinting financial generosity. He would without a thought expend his last coin on anyone who needed it, with no regard for his own well-being. And he did this repeatedly, constantly: that was just who he was. Harry was the first graphic example I have met of someone who exhibited this rare and strange phenomenon. His own existential security didn’t matter to him if he had to choose between helping someone in need—even if they were undeserving of it—and staking a claim to his own last meal.

On most nights, Harry would lead and sponsor a large gathering of poets and artistic hopefuls—sometimes as many as ten—to the Black Market, a bumpy, uneven yard filled with stalls, kiosks and eateries where university students and workers converged to dine. Harry loved jollof rice, beans, fried plantains and fish, which he would eat very slowly, delicately savouring every morsel amid the staccato snatches of spicy conversation that ricocheted all around him. More precisely, the Black Market was a stretch of undulating dusty red earth, similar to that of the North-West or Northern Cape provinces of South Africa. It tottered on the fringe of things, as if beyond the pale of institutional authority, devoid of identifiable future prospects, a dense, miniature, tropical ghetto tilting awkwardly into a void. But for Harry and his motley crew, it provided much-needed refuge from the ceaseless hurly-burly of the more centralised areas on campus.

Harry’s great talent was being able to serve as a constant magnet, indefatigable motivator and catalyst for all manner of creatives at a crucial time in Nigerian literary history, when elder literary heroes had become too distant or jaded to act as vital sources of inspiration and encouragement. He became the diffident face of a new literary generation in need of succour, shelter and literary resources. He also became a mascot that preferred to operate behind the scenes. He didn’t need to regularly deliver literary masterpieces. And it is no coincidence that after he had completed his important role as catalyst and nurturer, another generation of literary stars, comprising Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Seffi Atta, Chika Unigwe, Helon Habila, Toni Kan Onwordi and Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, among many others, burst through the international literary scene.

- Sanya Osha is the author of several books including Postethnophilosophy (2011) and Dust, Spittle and Wind (2011), An Underground Colony of Summer Bees (2012) and On a Weather-beaten Couch (2015) among other publications. He currently resides in Pretoria.