Ableism and the silent roar: The JRB Francophone and Contributing Editor Efemia Chela travels to Burundi with Roland Rugero’s novel Baho! in The JRB’s Temporary Sojourner series.

You cannot strike a mute: It’s like drowning a blind man in light. The action would be an insult to the divine hand that fashioned him.

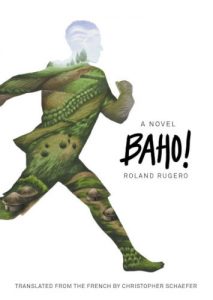

Baho!

Baho!

Roland Rugero (translated by Christopher Schaefer)

Phoneme Media, 2016

Baho!, the second novel by Burundian author Roland Rugero, is unique in the sense that the main character, Nyamuragi, never speaks. He is mute, and the constriction of his world that comes with being differently-abled shapes the contours of the story. As representation and diversity move to the forefront of discussions about good literature, and more demands are placed on authors to make their work more inclusive—to strive for a level of realism that gives marginalised characters dignity—this book is right on time. It also happens to be the first book from Burundi translated from French into English.

We learn about Nyamuragi’s complex existence in fragments, mainly as he drifts in and out of consciousness after being beaten up by an angry mob. We learn that he grew up extremely close to his parents but that they were killed in the war. He loves food more than he does people, and spent his childhood herding the family’s sheep. As a child he was expelled from ‘the white man’s school’, discriminated against because of his disability, and this marks a turning point in his life. After his expulsion, he no longer attempts to be understood, pre-empting rejection by those who can speak. He keeps to himself, and uses only essential gestures to get by:

Born incomplete, he had settled for living out his inadequacy. Just for himself. Without making it a tragedy or a question of resisting an accursed fate. One must not fear what is.

Nyamuragi isn’t the only mute presence in the book. His creator, Rugero, is selectively mute about the ethnic cleansing and civil war that began in Burundi in 1993—a tragedy which is often overshadowed by the comparable, concurrent genocide that took place in neighbouring Rwanda. Burundi is home to Hutu and Tutsi people, but you wouldn’t know it from reading Baho! One could argue that the omission of the ethnic cleansing amplifies its presence: we notice it is missing; we await its mention. At the same time, it frees us from re-encountering a narrative we know, or think we know, all too well. Instead, we are permitted to consider Burundi afresh, through a story that isn’t framed by ethnicity.

Vitally, however, removing explicit reference to ethnicity doesn’t water down the flavour of Baho!. Each chapter opens with a wry or chagrined Kirundi idiom:

Amagara ni amazi aseseka ntibayore. Life is like water that spills onto the earth, never to be gathered together again.

These aphorisms carry the reader into a world of custom and respect, ideas that make sense in the setting of Hariho village life. But these concepts hinge so delicately on the agreed context, an often unspoken on, that things can go disastrously wrong at the merest delicate finger of a breeze.

Baho! opens with the lines:

It’s November, and the heavens are naked.

Ashamed, they try to tug a few clouds over to cover up under the merciless sun, which brings their nakedness unflinchingly to light.

The central thread of the book begins when Nyamuragi, sitting by a stream, needs somewhere to relieve himself. He approaches Kigeme, a teenager who has been washing her clothes, to ask her where best to go, but his gestures are mistaken for sexual advances. He handles the situation poorly, owing to his social awkwardness, and tries to silence her screaming by putting a hand over her mouth so that he can explain himself. He only succeeds in frightening her further, and ends up having to flee for his life pursued by a band of men.

Rugero’s elegant prose style saunters between the heated conversations in the village, which is incensed by Nyamurugi’s ‘crime’. Incidences of sexual assault have been multiplying in Hariho. This, combined with two unusually dry months during the rainy season, makes for a village already on a knife edge. Gossip proves to be the fastest land mammal, and Nyamuragi’s sins are blown out of proportion. He is scapegoated and accused of rape. Rugero writes quite a stark procession to the novel’s climax, inviting the reader to consider how outsiders are treated—and the often inherent fatalities of ableism. One man implies that Nyamuragi’s guilt is obvious by saying, ‘He speaks strangely’, as Nyamuragi gargles in fear. You cower at how little is needed to condemn someone, and how easily mob justice gambols towards violence.

The wise voice of the other main character, a one-eyed old woman, creates a beautiful reflective counterpoint to the chaos of the present. She ruminates:

In Kirundi, ejo means both ‘yesterday’ and ‘tomorrow’!

This revelation occurs to the old woman on the footpath behind the mute.

Tomorrow and yesterday: two different times, a single word to label them both. Two places in time, a single name. As a result, one becomes the other. Perhaps this is a linguistic mistake. Or maybe ‘tomorrow’ and ‘yesterday’ meld into one another, because they contain two chimeras: past and future. Perhaps we just haven’t been able to find a better word to refer to the content of time gone by than the one for time to come.

In this slim but layered book, Rugero’s gift for dialogue sparkles, and news of Nyamuragi’s ‘crime’ spreads at the swift pace of market banter, which in turn exposes the rife sexism and misogyny in Hariho. The conversation switches from a man looking to buy a rope, to someone talking about Nyamuragi, to a man declaring to a hawker:

‘One rope, and make it a good one!'[…] ‘My father told me this morning that they’ve caught a big-time crook. He ran for almost six hills before the people caught up to him, and then they still had to sic the dogs on him. A guy who stinks like swine, with gigantic toes and hands like old banana tree leaves.'[…] ‘My little girl is about to turn three now, and I think that I should knock up my wife and see if I can get a boy.’ […] ‘So, shall we go? I brought a condom! Quick, before my wife comes back from the market! Are you scared? But of what? Me? Well are you sick, or what? Anyway, you’re not going to heaven with that thing of yours, better enjoy life here on earth!’

People swear the truth in conversation by saying: ‘May I knock up my own daughter if …’ When the wise one-eyed woman tells a traditional tale about a beautiful, single young women, the men in the story insist she must marry as soon as possible, as she is a ‘sterile heifer dying for want of impregnation’.

The one-eyed woman situates us in Hariho’s local culture while showing how times have changed. Talking about the current routines of the men in the villages she notes:

The men drank. Excessively. […] One rarely said that a man was ‘drunk’. No, he was ‘beer-sated’.

The village’s various hierarchies of power comprise the real social ill in Hariho, but its members choose the quick condemnation of someone who literally cannot speak in defence of himself over addressing the foul roots of their problems.

Baho! was first published in France in 2012, and subsequently in English, translated by Christopher Schaefer, in 2016. Although it came out before the ongoing #MeToo, #TimesUp and #BalanceTonPorc movements, one can’t help but read the impetus driving them as the same one providing the novel’s backdrop. We’ve killed all our idols and our heroes have been cancelled. Where do we go to now, after we’ve outed the lechers, the misogynists and the abusers? We still don’t know, and as the days pass we wait to hear another familiar name in an awful new context. Baho! didn’t intend to answer these kinds of questions, but its open ending wisely reminds us that there is work to be done: spaces to be filled and notions of justice to be questioned; the stopping of all insults to the divine hand that fashioned us.

- Temporary Sojourner is a series of articles by Contributing Editor Efemia Chela on fiction from around the African continent. Reading is the cheapest way to travel, after all. This is the sixth article in the series, which draws its name from the eponymous collection of short stories, first published in 1989 and reprinted in 2011, by Editorial Advisory Panel member Tony Eprile.

Editor’s note: This review comes from a collaboration between Phoneme Media, which publishes ‘Curious Books for Curious People’, and The JRB. The award-winning non-profit is shaking things up in fiction by publishing high quality literature, supporting writers’ and artists’ work in translation, and promoting cross-cultural understanding.