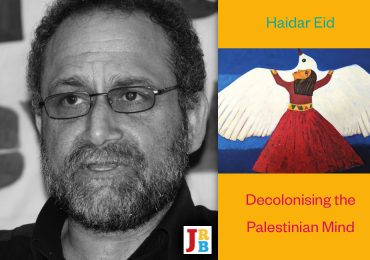

The JRB is proud to present an excerpt from Roland Rugero’s novel Baho!—the first Burundian novel to be translated from French into English.

Baho!

Roland Rugero (translated by Christopher Schaefer)

Phoneme Media, 2016

Baho! is the featured book in this month’s Temporary Sojourner series. Read The JRB Francophone and Contributing Editor Efemia Chela’s appraisal of the book here.

Phoneme Media has shared an excerpt from Baho! to accompany the review. In the piece below, we meet Nyamuragi, Hariho and the beginning of trouble.

Read the excerpt:

Chapter II

Nkunda kurya yariye igifyera kimumena amatama

The glutton ate the snail and it made his cheeks explode

With her left eye, the one-eyed woman tries to make out the pack of pursuers.

With the other eye, her bad one, she searches her thoughts. Tears escape them both. It is hard work with sweat trickling down. One eye makes out reality, and the other seeks the explanation for its harshness. One sees, and the other deliberates. The old woman’s comprehension in either case is muddled.

By the time the sun’s luminous fingers came to rest on Hariho’s fields, his neck was already sore. Undeniably, nights are cold in these parts.

This morning he had come down to this trickle of water to rest, like a mosquito sated after a night pumping blood from the depths of tired and world-weary veins. He was calm, his mind flush with images of last night and his belly full with the fare he had swiped here and there during his social calls.

All in all, he is quite pleased with himself, for his hunger was appeased. That is wisdom itself, he muses.

In the peacefulness of this morning, he thought back to the evenings of his childhood. They were long gone, ten years at least. The sights and sounds had remained with him—the fresh wood, the banana tree’s moist leaves, the fields nestled right up to the hills, bulls bellowing their greatness, and cows reflecting the sunset’s soft orange light. He recalled the dusk ushering in those childhood nights. Even now, he can see it all.

When the sun departed, evening would sweep in, and the biting cold breezes that crouched in the valley’s depths would climb the hills and skim the houses preparing for night. They would catch the smoke rising from chimneys, and then, in passing, greet the youths returning home with water jugs on their heads.

Everyone was heading home, up to the hamlets perched on the hills. Slowly, in fits and starts, in the company of good friends.

He remembered how a hint of cold wind would join forces with the moon to enter the courtyards encircling the Harihais’ homes, and slyly set about tickling the peaceful country’s children. The little rug rats had no fear of such provocations: they were safeguarded by a short-sleeved shirt or a light sweater, paired with shorts here or a skirt there. The children played with elements of nature, for they were nature. Umwana si uwumwe, tradition reminded them: ‘A child does not belong to any one person exclusively,’ even its father or mother. That was how the elders explained that all families were linked. All formed but one: the community of life. Life was transferred during birth, it fed on nature and was made real through it. Umwana si uwumwe. The child—that bit of humanity, that bud of life—belonged to none except nature. To its fellow creatures and to its cradle, earth. Joyous, it was with trust then that Hariho’s children threw their small frames into the cold evening. Trust and courage.

His right foot is folded beneath his buttock. His eyes are distant. On one side lies a shepherd’s crook he has skillfully decorated with interlacing black lines. Occasionally, he nods gently. Those all-nighters can be punishing.

At ten years of age, he began venturing out from the family seclusion to play in the neighboring households. He heard new stories. He ate new dishes. He was content when he returned home late, around eight in the evening. Sometimes he would have a second meal, prepared this time by his mother’s thin fingers. A strange idiosyncrasy of hers was that from a very young age she had refused to wear sandals. She maintained that they were uncomfortable, that the soles of her babouches distanced her from the nourishing earth. Her own mother would clean out the impressive crevices in her feet, black with dust, before each neighborhood party.

As for his father, in accordance with his age and generation, he wore an ikoti, a long black jacket that he alternated with a baggy gray sweater that reeked of tobacco. His father spoke little and drank much. Always in silence. He would take stock of the day, buried in a cloud of pungent smoke, silver wisps escaping his smooth dark lips. These fluids swept before his eyes, teary but lively, yellowing the enamel of his teeth, once white as milk, and climbed back up the black walls of the house. For a long while his father would remain crouched before the fire, his son imitating him. Words were rare in that family, laughter even rarer.

His memories flow peacefully as the nearby stream. Other men—elsewhere, not those of this quiet abode— those men had their fields, cows, goats, and hogs to yield a profit, and bottles to finish off with one another each evening. His father had known those men only a little. In the last few months preceding his parents’ ‘departure,’ his father had burrowed deeper and deeper into his jacket. Was it fear of the cold perhaps? A sign of fragility, his limbs forgetting how to warm themselves? He would return home early, only to busy himself by stubbornly wandering the fields around his rugo. Then, with the sun’s departure, he would go in quest of banana beer. Returning home, he would sit back down beside the hearth to sip alcohol that he would never finish.

His father rarely spoke to him. He had never seen him wash his jacket. Eventually the thick material had become an extension of his skin. Nyamuragi had come to believe that his father suffered, but, in the reverie that pervaded their dwelling place, suffering was grounded in silence and so, unencumbered, the world pressed on.

His eyes still riveted to the stream, Nyamuragi lets a sigh escape. Life goes on.

He stretches his neck toward the lapping water of the Tuzi, a stream that skirts the southern edge of Kanya. Nyamuragi has just washed his face, calm and serene. The reflection in the earth’s lifeblood mirrors back a light complexion, a full, but rather short beard with very black and very thick hair standing on end, dark eyes, and a nose that is a little too large, a little too pointed, and all too human.

Nyamuragi, the mute, has spent a good quarter hour asking himself where the water comes from. But to this weighty question he has found no response. He is superstitious; he believes in man. And since one should seek meaning only in the comprehensible, he endeavors to come to terms with his fear of man. Man dismantles, creates, and destroys again. That much is apparent.

Behold, the master of this world.

On the bank of the Tuzi, not far from the mute, women—or rather girls—converse. They have come to draw water. It is cold. Some phrases to spice up the morning won’t hurt anyone, especially not the birds recounting their dreams in the distance.

‘Mahoro, Kige’ ‘Peace, girl.’

They respond, ‘And peace to you!’

‘Have you found your aunt’s chicken?’

‘No, unfortunately! And I can’t possibly understand where she might have spent the night! Perhaps someone stole her?’ It was inconceivable that a chicken could get lost.

‘Nyamuragi seems to be lost in his thoughts today!’ adds Kigeme.

Hearing his name, he turns his hairy body towards the two conversing adolescents. With a smile. His name often bothers him. He knows what it means, but he doesn’t believe that he belongs to the category of mutes. Nyamuragi is well aware that the mouth’s sounds come from oscillating jaws and a deft tongue quivering in the palate. Both parts function marvelously for him. His strong teeth are particularly renowned in these parts—they serve as an emergency bottle opener.

He dismantles chicken and other meats with force, gleefully cleaving beef and pork apart with no discrimination whatsoever. His tongue is a trusted weapon in that great battle to which he has been summoned: He loves to eat.

Nyamuragi is often hungry. His round belly sticks out so much that he can barely manage to cover it all up with his ochre sweater. It sticks up just above a black pair of pants, which are rolled up to the ankles and held together by pins and two multi-colored buttons. The ensemble is covered by a jacket, which is also black with orange stripes. Nyamuragi meticulously cares for every inch of his six foot one figure.

He eats much and with gusto, drinking beer as well. He rarely gets drunk, preferring instead to laugh at the spectacle of others who do. It entertains him: their vice is drink. His is gluttony.

On the Tuzi, one of the young girls leaves the area. Her container full of water, she says, ‘Well, I’m off to look for some sweet potatoes to cook for lunch. And then this afternoon, you know my aunt is expecting guests …’

Kigeme responds, ‘Ah! Nshimi, thank God. Remind your little brother to bring back the top he took. In any case, we’ll see each other this evening. I’ll be staying a little longer to wash my jumper.’

Nyamuragi doesn’t understand how it is that he is mute! His jaw works. His tongue works. The main thing is to produce clear and audible sounds, words and phrases that are meaningful.

When he was still very little, four years of age, his mother took him to see a wise relative to diagnose his sickness. The verdict returned: The boy is in good health, he simply doesn’t want to speak! There was nothing more to say. It was clear. He wasn’t sick, it was all a masquerade. His father had grumbled that evening, before plunging his thin straw into the calabash full of urwarwa, banana beer.

Nyamuragi had learned too early, and at his own expense, that life is composed of dualities. Coming and going. Rising up and falling down. Left, then right. Before, after. Crying and laughing. Working and sleeping. Fatigue and rest. Hunger, then a meal. Drinking, then thirst. The tree that grows and the axe that lays it low. The cow’s udder swells, and tugging fingers empty it. The snake bites, and a club smashes its head. To give and to receive. Here and there. Above, below. Sow and reap. Youth running all over, old age running to its end. The fat muscle, the bare bone. Living and dying. Cries of joy, laughs of pain. No! Perhaps crying and laughing. Joy and laughter. As long as that duality is present in every breath, life will continue with ease; between the two poles of the duality, everything can be compared. Take the two phases of the cycle: mix them up and you will confuse yourself—pain, joy, crying, laughing. Nothing is certain anymore. Everything is all mixed up—even earth and heaven!

Early on, Nyamuragi had learned the relativity of things and the infinite richness of reality. He was born a connoisseur.

Editor’s note: This review comes from a collaboration between Phoneme Media, which publishes ‘Curious Books for Curious People’, and The JRB. The award-winning non-profit is shaking things up in fiction by publishing high-quality literature, supporting writers’ and artists’ work in translation, and promoting cross-cultural understanding.