The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec chatted to City Editor Niq Mhlongo about the banning of Inxeba, writing to music, and his brand new book, Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree.

Niq Mhlongo

Niq Mhlongo

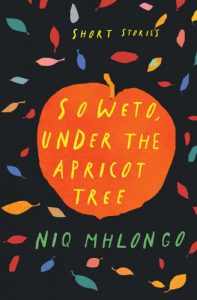

Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree

Kwela Books, 2018

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: I’d like to open with a question about the recent reclassifying of the film Inxeba. You worked at the Film and Publications Board for a number of years, could you talk a little bit about your experience of working there?

Niq Mhlongo: I worked at the FPB from 2011 to 2017 as both classifier and chief classifier of films, games and publications. I learned a lot during those years about the legal and regulatory prescriptions that govern the FPB, including the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (PAJA), the Films and Publications Act, as well as the classification guidelines. The classification guidelines are the most important tool in the classification process, as they help classifiers to determine what may be harmful and disturbing to children before deciding on a proper age restriction.

For every age restriction given to a film, game or publication by the classification committee, the decision must be followed by logical, rational, credible, valid, consistent and reliable reasoning. This means that classifiers are bound by the law to work independently and objectively without fear, favour or prejudice.

The JRB: As something of an expert, what do you make of the reasons given for the X18 ruling by the appeals tribunal?

I read the appalling, pedestrian judgment by the appeals tribunal for the FPB that reclassified Inxeba, and in my opinion the ruling of X18 is illogical, full of prejudices, homophobic, undesirable and embarrassing. In reclassifying the film the tribunal didn’t apply the legal prescripts correctly, and their decision is flawed and unlawful. One clear example is that they gave the film 18X (SLNV). First of all, there is no such age restriction, according to the guidelines. The guidelines only have X18, and this does not come with classifiable elements of sex, language, nudity or violence. A person that is familiar with and has properly applied the guidelines would have noticed such a fundamental error. During my six-year tenure at the FPB I never witnessed such an embarrassing judgment. I’ve watched over two thousand porn films, and there is no way in which a sober person could claim that Inxeba is porn. Porn films lack artistic merit, dramatic value, or a storyline.

Inxeba is an excellent film that is highly educational, and it teaches viewers about love, same-sex relationships, tradition and the rite of passage into manhood, among other things. I’m very concerned that reclassifying it implies serious incompetence within the appeals tribunal. They found the film to be blasphemous, explicitly sexual and degrading to women with coded language. My challenge to the FPB is that the tribunal must have a serious workshop where they watch a few porn films. That way they will have a clear understanding of what a porn film is like, because Inxeba is definitely not that. The sex scenes in Inxeba are implied rather than explicit. It is clear that the main intention of the director was not to make viewers feel aroused when making those sex scenes, but to enhance important dramatic values. The tribunal deliberately failed to understand this and chose the route of homophobia instead.

The JRB: Thank for explaining that, Niq. Let’s hope the film’s producers are successful in overturning the ruling.

To turn to your new book, Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree—I know the title is inspired by a real tree, at your home in Chi Town. The final story of the collection explains a bit about the history of Soweto’s fruit trees, and how they were planted by the apartheid government in the nineteen-sixties. Could you talk a little bit about the symbolic significance of your apricot tree?

Niq Mhlongo: All my stories are born out of real-life experiences. Some of these experiences are my own, some are other people’s; some are hearsay, dreams, my thoughts and observations. I think I’m good at fictionalising reality. Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree is about those stories that I listened to as they were told to me by friends, strangers, and relatives while sitting and drinking beer under the apricot tree behind our house in Soweto. The apricot tree is like a rendezvous among my friends. Even when I’m not in Soweto my friends and even strangers will meet and drink under that apricot tree. The other day we locked up the house and went on a weekend away. When we came back there were several strangers sitting under the tree, talking and drinking. A neighbour had parked his two cars, and another one had put her clothes on our line. Although we were angry at these people, in one sense we realised that the tree is a symbol of our communal way of life as black people. That’s the reason it’s not very easy to break into a house and steal something in Soweto. Everyone knows everyone. My short stories are in a way trying to appreciate this township solidarity without romanticising it.

The JRB: ‘Curiosity Killed the Cat’ is slightly different: it centres around a subject that many South Africans are still not comfortable with—black people in the suburbs. The story is far-fetched in some ways, and yet the violence and racism the black family face are very real.

Niq Mhlongo: That story explores binaries: between township life and suburb life, between being rich or poor, black or white; between being liberal and/or racist, between African traditions and Western ways of life, between Christianity and secularism. It is the story that I wrote during the time when there were a lot of racist utterances in our public discourse, made for example by the likes of Penny Sparrow and a few schools around South Africa. I decided to write the story as a form of protest against all these forms of racism.

The JRB: Zakes Mda, in Rachel’s Blue, and Kopano Matlwa, in Period Pain, have explored the emotional trauma that comes when a child is conceived of rape, something that haunts South African society. Your story ‘My Father’s Eyes’ touches on this subject. Was this something you specifically wanted to explore?

Niq Mhlongo: Initially I wanted this story to explore fatherhood, motherhood, parenthood and identity. I wanted to talk about the burden and joys of motherhood, and about patriarchy. But the characters in the story overwhelmed me, and I allowed them to lead my story toward themes of trauma, memory and secrets.

The JRB: You’re known as being a writer with a keen sense of place, those places being Soweto and Johannesburg. For a story like ‘Roped In’, would you revisit the places mentioned—the Soweto mine dump, for example, as the dawn light hits it? Or are these places embedded in your memory already?

Niq Mhlongo: Well, that story was inspired by a specific visit. About five years ago a friend of mine got a tender contract to close the mine shafts around Joburg. One day I decided to go to the open mine shaft around the Riverlea area where his workers were closing a big, open mining hole that I learned was several metres deep. The workers, who were from the squatter camp nearby, started telling me some stories. One of the stories was about the police chasing some thieves one day. The thieves ran towards the hole, and the unsuspecting police fell into the hole and were never found. They also told me of the illegal mining going on at the mine dumps and how they had to fight against the heavily armed illegal miners who were against the closing of the shafts.

The JRB: A number of your stories feature burials or cemeteries. In ‘Avalon’ a character says: ‘Cemeteries like Avalon are just another convenient place to meet old friends and show off your new car and designer clothes.’ But funerals and the unveiling of tombstones are also events where tradition, family histories and stories emerge, where the older and younger generations have a chance to interact. What was the reason you centred so many of the stories in this collection around these places or events?

Niq Mhlongo: I was born in Chiawelo, the Midway part. My home is literally facing Avalon Cemetery. All my life on weekends I would be woken up by a hearse siren, because Avalon is the biggest cemetery in South Africa, where millions of Sowetans have buried their dead. I guess this caused me to internalise death and burial so much that it has become sort of my weekend diet. But it’s not just me; death has become so much part of our life in the township that it no longer scares us. In fact, the ‘after tears’ party is something most people look forward to. We have experienced so much death, from apartheid brutality to HIV and Aids, that it has almost lost its meaning. And it is within these sombre spaces that stories are born and told.

The JRB: Music also plays a big role in your writing, and whenever a song is mentioned—’Sister Bethina’ by Mgarimbe, ‘Khona’ by Mafikizolo, ‘Jikijela’ by Letta Mbulu—I searched for it on YouTube and played it while I was reading. The only one I couldn’t find was ‘Mayanka’ by Teenage Lovers! Do you listen to the music you are writing about while you’re writing? Can you talk a bit about the importance of music to you?

Niq Mhlongo: Music is life. It is a beautiful way of storytelling that syncs well with the mood of a human being. I’m a proud owner of more than five thousand CDs, which I’ve been collecting since 1994. Every time I want to stimulate my creative juices I listen to music. For me, music tells big stories in an abbreviated, poetic fashion. The duty of a prose writer like me is to expand the stories that have already been told by poets and musicians. Music is definitely a source that I draw my stories from.

The JRB: This is your second book of short stories, after three novels. Are you going to keep going with the short form?

Niq Mhlongo: Affluenza, my first short story collection, was an experiment gone right. Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree is an experiment mastered! So yes, I will continue to write both short stories and novels. I enjoy writing both. At the moment I’m busy writing a novel that I abandoned some five years ago. It is now at an advanced stage. But the beauty about writing a short story is that you can just pick a theme and focus on it. And if you do it well, you’re in a very addictive, beautiful game.

The JRB: We’re looking forward to it. Finally, could you recommend some recent reading? Are there any books you have read over the past year that you have particularly enjoyed?

Niq Mhlongo: I think Nthikeng Mohlele is one of our most gifted writers. I’ve had the pleasure of reading his Pleasure and now looking forward to Michael K, his latest offering. I also recently enjoyed Always Another Country by Sisonke Msimang.

The JRB: Well, you’ll be pleased to hear that we have an excerpt from Nthikeng’s new book in our current issue! Hope you enjoy it, and thanks for your time, Niq.

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor; follow her on Twitter.