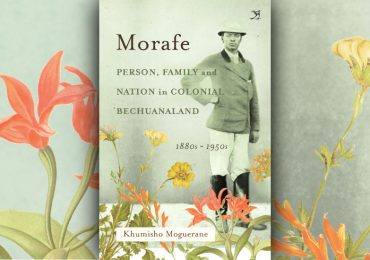

Period Pain

Kopano Matlwa

Jacana Media 2017

Kopano Matlwa burst onto the literary scene in 2007 with the publication of her debut novel Coconut, which became a bestseller and won the European Union Literary Award. Her second novel, Spilt Milk, won the Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in 2010. Her latest novel, Period Pain, was recently shortlisted for the Sunday Times Barry Ronge Fiction Prize.

Kopano Matlwa burst onto the literary scene in 2007 with the publication of her debut novel Coconut, which became a bestseller and won the European Union Literary Award. Her second novel, Spilt Milk, won the Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in 2010. Her latest novel, Period Pain, was recently shortlisted for the Sunday Times Barry Ronge Fiction Prize.

In an interview with The JRB, Matlwa discussed her new book. Each question is contextualised with a quote from Period Pain.

If this were apartheid, I’d be one of those quiet white people who just stood by and watched it happen.

The JRB: Despite its brevity and humour, Period Pain is a novel of big ideas. You manage to balance hefty topics with a lightness of touch—and a startling brevity. Did that come naturally to you, or did you have to work at it?

Kopano Matlwa: Hmm … that’s a difficult question. It was a hard book to write, but I think that had less so to do with the writing style itself but rather because it dealt with themes very close to my heart and it forced me to work through my own big scary questions when writing it.

I guess this ability we have – to go from looking at street signs and roundabouts in a learner’s license study book to overtaking trucks on the highway – makes us a little reckless when it comes to what we think we’re capable of achieving.

[…]I see now that there was actually a lot of luck in my getting to this point, and perhaps a lot of unseen effort by those around me.

The JRB: The myth of the self-made man or the rags-to-riches story, with Benjamin Franklin perhaps the most famous example, has a powerful foothold in American consciousness, despite current thought debunking it because of the huge and often unacknowledged role that social-structural factors and even luck play in these narratives. It strikes me that the myth is equally powerful in South Africa, and even more pernicious. The idea that success is obligatory if you’re young, black and free is psychologically damaging on a national scale. Did any of these ideas fuel your creation of Masechaba?

Kopano Matlwa: No not particularly. I don’t think Masechaba viewed her dreams necessarily through the lens of being ‘young, black and free’ but rather hers were just the dreams of a young person with the hope of making an impact on the world, regardless of their race or gender.

I’m no good at arguing. I get too overwhelmed and my mind goes blank, so I say nothing.

The JRB: We know, of course, that Masechaba is in fact very good at arguing; she does it eloquently and elegantly in her diary. But these arguments are one sided. The decision to write the novel as a diary means Masechaba becomes a complex character, we see her inner self as she presents it to us, but we also see, through her reportage, how she presents herself to other people, and how they react. What were your reasons for using the diary form?

Kopano Matlwa: It kind of came to me as diary entries right from the start, and resisted being written any other way, so of fear of disrupting the ‘flow’, I let it unfold the way it wanted to.

If my mind were to fall apart, what would become of me? […] Things are spiralling out of control.

The JRB: I hear echoes of Chinua Achebe’s famous work here, and there are threads that connect the novels. But there is a vital difference: at the end of Things Fall Apart, Okonkwo hangs himself. In Period Pain, Masechaba too experiences extreme darkness, but out of it comes her daughter, “so perfect, so magnificent”. In fact the book is almost a litany of shameful societal sins and personal tragedy – suicide, racism, xenophobia, rape – which ends on a tone of hope. Was that hopeful tone an important ingredient for you?

Kopano Matlwa: Without hope what remains really? One has to remain hopeful, defiant even. I think that’s what is so exceptional about us as South Africans, we are a defiant people, we continue to believe in ourselves and what we are capable of achieving as a nation, despite the odds in many ways being stacked against us. Masechaba is no different.

There is no vocabulary for the pain I feel. How do I construct a sentence that explains that they made me into a shell of myself? Not ‘like’ a shell of myself, but an actual shell of myself? How do I explain that what they stole from me is more than just my ‘womanhood’ or any of that condescending stuff people like to talk about, but a thing that once lost can never be found because it is unnamed? How do I explain that the languages at my disposal can’t communicate the turmoil I have inside?

[…]‘I was raped.’

Dr Phakama wants me to say it. She says it will help. She says by putting it in the past tense I can overcome it.

But when it’s your own life and you’re living it, there is never so clear a distinction. I’m still being raped even now, even when I’m not. I can’t say when one stopped and the other began. I am being rape.

The JRB: The failure of language as a tool to express what we know and feel – Masechaba encounters it both as a failure of words and a failure of grammar. Tying that in with the structure of the novel, where the narrative is broken up by poetic interludes, it seems that these unnamable things and feelings are best expressed when language is forced to become poetry, containing less meaning and more meaning at the same time.

Kopano Matlwa: Absolutely. What a beautiful way of putting it! I agree completely!

Nyasha shrugged. ‘It’s just a period South Africa’s in,’ she said matter-of-factly. ‘Growing pains.’

‘Like period pain,’ I said, trying to make a joke.

‘Yeah.’ She gave me a weak smile. ‘Like period pain.’

[…]Time moves slowly. Tshiamo’s old watch calls from my dressing table drawer.

‘Chronos, kairos, chronos, kairos …’

I wore it until the strap withered, and then carried it in my pocket until the face fell and cracked. So now it sits in my drawer raising its voice from time to time.

The JRB: Masechaba writes this diary entry in the fitful time after she is raped, when a moment of horror interrupted her day to day life, a dark inversion of how kairos, a godly moment, penetrates chronos, our quotidian existence. That’s deep. It also ties to the title of the book, Period Pain – a period of pain much more debilitating than is often acknowledged. At the same time, after she stops taking her medication Masechaba describes her feelings as “a kind of pain, a kind of pleasure, a kind of freedom that I like”. Do you think South Africa’s current pain is a symptom of our freedom, and a necessary step towards redemption?

Kopano Matlwa: Sho … I don’t know … if it is a symptom of our freedom, that pain is unjustly primarily experienced by those who are yet to taste freedom, so I’d hate to think it a necessary step towards redemption. Perhaps maybe a symptom of avoiding the necessary steps towards redemption, whatever those steps may be.

If I was to explain to her what awaits her, she would not understand. She is too young, and, anyway, to what end? The deed must be done, the jab must be given. Why spoil her morning with stressful information, when I will be right there by her side to comfort her when it is all over?

The JRB: The last lines of the novel. Masechaba is confident that by connecting with her she will be able to help her daughter overcome the necessary pain of her immunisations. Do you think there’s a similar solution for South Africa’s societal pain?

Kopano Matlwa: I doubt there is a single, one shot solution. Ours is a pain that has been centuries in the making, and perhaps the worst thing we can do is to look for quick fixes. But the idea that it will be a painful road to recovery is one that I think both Masechaba’s personal journey and that of South Africa’s share.

The JRB: Finally, could you share some books that recently inspired you, or books you recommend, or books you’re reading at the moment?

Kopano Matlwa: Sure. Books that inspired me:

Dr Seuss: Oh the places you will go!

Tsitsi Dangarembga: Nervous Conditions

Steve Biko: I Write What I like

Toni Morrison: The Bluest Eye

Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche: Purple Hibiscus