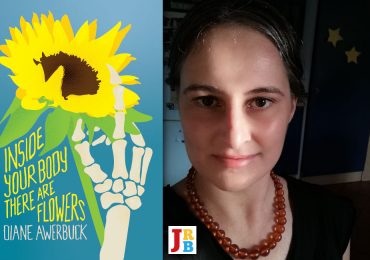

Second-wave feminism, mansplained: Diane Awerbuck finds much to disappoint in Stephen and Owen King’s Sleeping Beauties.

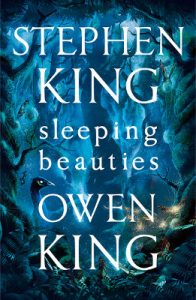

Sleeping Beauties

Sleeping Beauties

Stephen King and Owen King

Hodder & Stoughton, 2017

‘I hope you have children one day.’ It’s the parental curse, isn’t it? You’ll only really understand the heroic banality of raising other humans when you have to do it yourself. And by then it’s too late for regrets.

My mother was a weary woman. She had a lot going on: more so than other mothers, who also had full-time, underpaid, jobs; or other people’s children to feed and love; or needy, useless partners who meant well but only added their own poverty to the household burden.

But my mother also knew how to keep happy. It’s a secret that few people discover, no matter how old they make their bones. Happiness is a by-product. It happens when you’re doing something else. Sometimes that thing is useful, often it’s reading a good book.

My mother used to collapse on her bed in the blinding, sweltering Kimberley afternoons in the forty minutes she had to herself before she had to mark a set of books before morning and do everyone’s homework with them before bathtime and cook something healthy before evening and do it all like she meant it and wanted it and like this was what a woman’s life was meant to be—like you could be a resource, and not a person, and that was okay.

What she liked to read was horror. Fright and gore were her thing. The more frightening and gory, the better shape she was in when she got back up, like Lady Lazarus, ready for real life. Those library books were, it is not too much of a stretch to say, one of the reasons she could rise again. Because those novels gave her something, instead of demanding something back from her overworked body and soul.

That was how I found Stephen King—when I was sifting through the piles of books by her neat, deprived bedside. Because I was also looking for friends. I could see what they meant to her. She was voracious, my mother. It didn’t have to be King: it could be Virginia Andrews or Dean Koontz or anything with a cover where the title was raised, a kind of Braille for the non-blind. I used to run my hungry fingers over those covers. I couldn’t wait to get inside.

But that changed after a while. I got specific. You learn, don’t you, what true, strong writing is—and what writing will let you down because it’s weak or self-indulgent. Those writers you shouldn’t trust.

But Steve: Steve I could trust. Man, I couldn’t believe a grownup was writing this stuff! The vampires and firestarters, the secret shops, the giant spiders, the daughter-fucking dads, the worlds twinned with ours that had always been there—and the sweetness and the light that he always came back to in the end. Isn’t that what it’s about, always? The happy ending? Or at least the most satisfying one? The one that you can live with?

What I liked the best was when he talked directly to you—to me—in the introduction, or in the endpages. He liked to talk, Steve, and what he liked to talk about was how he had come to the story, or what it meant to him. I used to read those musings and think, Yes. Yes. This is the way I want my life to be. I believed in the entire universe of Castle Rock. I kept it inside me, secret as happiness, until I could find like-minded companions. I knew they were out there.

Steve’s let me down a couple of times, but I’m forgiving. He has, after all, been with me my whole reading life. It seems like I’ve been reading The Dark Tower series for as long as he’s been writing it. When I first heard that there was a new book out, co-written with his son Owen, it gave me a thrill. Thank God, I thought. Maybe Steve is going to die sooner rather than later, but someone is going to keep something of him alive. And who better than a person who’s grown up in that world beside him? Who’s held his hand in the bloody bathrooms and the haunted hotels and the green places in summertime Maine?

So writing this feels like a betrayal—of my own reviewing practice, but also of my own history as a reader, and as the child of a reader. For, despite their best efforts, Sleeping Beauties is the stillborn book of two loving parents. It’s hard to say why this novel is so disappointing, but I’m going to try.

Sleeping Beauties is a thought experiment: What happens when almost all the women on the planet get infected with the Aurora virus? They spin themselves cocoons and hibernate, is what, and they are mindlessly murderous when they are disturbed. The cocoons allow the women to be transported via a magic tree (think Yggdrasil) into a socialist–feminist utopia.

And the men? Some of the nastier ones burn the sleepers in their bindings. Some of the less nasty but still patronising ones try to save the day. The eventual climax of the action centres on Dooling Correctional Facility and the unlikely entity of Eve Black (a name nicked from The Three Faces of Eve, the real-life nineteen-fifties study of Chris Costner Sizemore’s dissociative identity disorder).

Because the Kings are the Kings, Sleeping Beauties is not terrible. But it’s meh. And when you’re relying on legacy tactics, you had better deliver. The book is lumpen and self-congratulatory, and it has not a single original idea or turn of phrase between its covers. It’s second-wave feminism, mansplained. The most exciting character in the whole seven-hundred-plus pages is a talking fox. What does he have to do with the story? Not a single fucking thing.

If you want to read a book about women getting strange powers—and you do, dear reader; you really, really do—read Naomi Alderman’s The Power instead. It makes everything else die in its shade.

And death does come to everything, I’m afraid. The readers among us will be a little more prepared for it. My mother died young. I’d like to say she read all the way there—that she finally caught up on all the novels she hadn’t got to—but towards the end the morphine made her crazy, and she just wandered the house, weeping with pain and making lonely notes to herself in hieroglyphics. The words didn’t work anymore. It was cancer, like the mother in The Talisman, which King co-wrote with Peter Straub and which is his most underrated work. I’m glad I read that book when I was young. It helped me navigate some terrible territory. Aren’t all mothers in all books versions of the writer’s? And of our own? Isn’t that the point of books—that even the least real of them should feel truthful and relevant, especially in the time of #MeToo?

I miss my mother. And now I miss Stephen King, too. But I’m going to keep reading. He has another son, Joe Hill, who’s just published Strange Weather. I’m going to read that next, and I’m going to love it. I’ve been a reader my whole life, and I can’t stop now. It’ll be something to tell my children.

- Diane Awerbuck is the author of Gardening at Night, which won a Commonwealth Best First Book Award and was shortlisted for the International Dublin IMPAC Award; Cabin Fever, a collection of short stories; and Home Remedies. She was shortlisted for the Caine Prize in 2014 and won the Short Story Day Africa competition the same year. Her more recent project is a collaborative notebook, As Above, So Below.

- Win a copy of As Above, So Below on The Reading List!

Image: Stephen King: Shane Leonard