Update: Naomi Alderman has since been announced as the winner of the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction

The Power

Naomi Alderman

Penguin Books 2016

Science fiction, be it fantastical or dystopian, emerged as a manifestation of anxious thought about the future, as seen from the present. Or, more accurately, about a present in which humanity seems poised to leap into uncertainty. Science fiction enters the what-if moment just as we leap across the fissure between the present and the unknown future.

But in a more fatalistic age, weightless science fiction has to do battle with heavy facticity. How does a genre so hospitable to ideas confront the brute nature of violence? Modern speculative fiction (the cagey adjective betraying a more contemporary mistrust of science as a vehicle of progress) is perhaps less concerned with things that aren’t possible than with possibilities that could occur in the here and now. Naomi Alderman’s The Power is such a work, running to 341 pages and taking as its subject the insidious ways in which inequality benefits men. The novel does this in a way that springs out of genre fiction’s ghetto, being trenchant social commentary of a piece with a film such as Jordan Peele’s excellent horror Get Out.

The Power is broken into sections with titles like ‘Ten Years Before’, which ominously signal a cataclysmic event. We run through the vignettes of four characters—Roxy, Tunde, Margot and Allie—who are windows through which to observe the coming storm. This is stock fare if you’ve watched a sci-fi television series in the last decade or so, but the narrative fills out rapidly. The novel is a baleful fable in which ordinary life is turned on its head by the discovery that women possess the power to release jolts of electricity, in doses ranging from gentle tingle to brain-cooking fatality:

And then it hurts. From the place on her forearm where Jos is touching her, it starts as a dull bone-ache. The flu, travelling through the muscles and joints. It deepens. Something is cracking her bone, twisting it, bending it, and she wants to tell Jos to stop but she can’t open her mouth. It burrows through the bone like it’s splintering apart from the inside; she can’t stop herself seeing a tumour, a solid, sticky lump bursting out through the marrow of her arm, splitting the ulna and the radius to sharp fragment. She feels sick. She wants to cry out.

As news of this strange ability spreads, men go from bemused disbelief, through righteous affront, to horror. In ways that seem all too exhilarating, given our present moment, the realisation that women are now stronger than men alters everything.

It’s not too difficult to acquiesce to this fantasy. Alderman crafts a story in which the very worst happens to a world that is unprepared for any shift in the regular order. When the newly established gynocentric territory of Bessapara institutes a series of laws limiting the movement of men, the mechanisms are easily recognisable:

Thus, we institute today this law, that each man in the country must have his passport and other official documents stamped with the name of his female guardian. […] Any man who does not have a sister, mother, wife or daughter […] must report to the police station, where he will be assigned a work detail and shackled to other men for the protection of the public.

Alderman’s novel runs us through the encroaching fear with brilliant fluency because what it talks about is already part of our reality. What could be stranger and more unsettling than a man’s fear as a woman appears out of the darkness on an isolated rooftop? The Power burrows into the very substance of what women experience on a daily basis and twists it about in truly horrible ways.

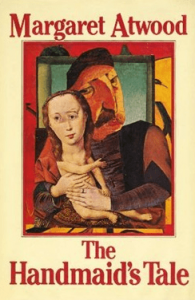

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is a shadowy presence behind The Power, which owes a great debt to Atwood’s exquisite display of how grotesquely normal the abuse of power can be. Alderman also lifts from Atwood the trick of artful scaffolding: what we are reading is presented to us as a historical novel written by a submissive man who is part of a Men Writers Association. A writer named Naomi provides condescending criticism. It’s a wonderful conceit.

The theme that the novel crystallises around—that power is blind and blinding in its effect—gathers intensity until the novel’s bloody ending, and in its stampede to its ceaselessly bleak conclusion Alderman poses some deeply taxing questions about human nature.

Those questions are answered briskly, in a tone that lacks ornament. Alderman dismisses temporality by imposing a processional present tense that causes you to read with an unblinking eye and the breath caught in your throat. The narrative is impelled by hard declarative sentences devoid of emotion (‘She doesn’t care to see what Mr Montgomery-Taylor does up there in the evenings; at least he’s not catting around the neighbourhood, and that girl earned what she’s getting.’). There’s the clever phrasal nuance of Zadie Smith here too, although Alderman’s narrative voice avoids conspiratorial expressivity.

The concessions to the aesthetic of science fiction—the sense that things must be shown in order to be real—are mercifully few. It can seem laboured that we need to see the power sparking, or that it needs to mark itself on the bodies of those it is used against. But these details take on the sinister buzz of a stun gun being readied for action. The scarring it leaves becomes a metaphor for a world whose boundaries are irrevocably altered.

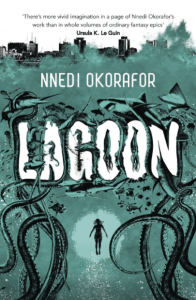

Perhaps one of The Power’s few weaknesses is that, while it is flavoured by multiculturalism of a very English kind (Allie, who becomes a deity-incarnate, is mixed race; Tunde, who is the media’s eye, is a black Nigerian), the treatment feels half-baked. Although the novel roams to Nigeria and India, it does so in the newsflash way an action-apocalypse film does, where reports from elsewhere merely confirm that what is happening at home is a universal terror. In a novel that sits in a category along with a text such as Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon, this is especially disquieting.

Perhaps one of The Power’s few weaknesses is that, while it is flavoured by multiculturalism of a very English kind (Allie, who becomes a deity-incarnate, is mixed race; Tunde, who is the media’s eye, is a black Nigerian), the treatment feels half-baked. Although the novel roams to Nigeria and India, it does so in the newsflash way an action-apocalypse film does, where reports from elsewhere merely confirm that what is happening at home is a universal terror. In a novel that sits in a category along with a text such as Nnedi Okorafor’s Lagoon, this is especially disquieting.

The Power is, in the end, a painfully affecting novel, however. As a work of speculative fiction it is magnificent—although it is also only dystopian if you could never conceive of a world in which women have as much power as men do now. Nevertheless, The Power doesn’t read like a thin allegory, nor a Soylent Green jeremiad against our present world. It’s a nightmare in which the lasting question seems to be: Given what we know, why would things be any other way?

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University; follow him on Twitter

Index

Authors

- Zadie Smith

Awards

- Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction

Books

- The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

- Lagoon by Nnedi Okorafor

Films

- Soylent Green, directed by Richard Fleischer

- Get Out by Jordan Peele

Topics

- Dystopian fiction