Ghanaian novelist and poet B Kojo Laing passed away on Thursday, 20 April 2017 in Ghana. The JRB gathered tributes from several writers, who give their thoughts below.

Born in Kumasi in 1946, Laing completed his schooling in Scotland, and studied in Ghana and Birmingham before earning an MA from Glasgow University in 1968. He returned to Ghana and worked in central and local government, as secretary of the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana, and from the mid-1980s, manager of a private school established by his mother in Accra.

Writer and poet Kojo Laing (1946-2017). RIP pic.twitter.com/OHmYqRtudN

— Chimurenga (@Chimurenga_SA) April 21, 2017

Laing’s literary career kicked off in the 1970s, when he began to gain notice as a surrealist poet. But it was through his novels that he gained widespread acclaim. His first, Search Sweet Country, was published in 1986, and won Ghana’s Valco Fund Literary Award for Fiction and the Ghana Book Award. Search Sweet Country was republished in 2012 by McSweeney’s, with an introduction by Binyavanga Wainaina, who calls it: ‘The finest novel written in English ever to come out of the African continent.’

Laing’s second novel, Woman of the Aeroplanes, was published in 1988, followed by a poetry collection, Godhorse (1989), and the novels Major Gentl and Achimota Wars (1992), which also won a Valco Award, and Big Bishop Roko and the Altar Gangsters (2006).

On the jacket of Major Gentl, Laing was described as having ‘a penchant for hunting, walking, playing football and planting trees’. But his main talents were defying expectations, genre, and even time itself.

A number of writers and academics have shared their thoughts and memories of Laing with The Johannesburg Review of Books, as we attempt to pay our respects to a writer who was painfully underappreciated in his lifetime.

Efemia Chela, writer and Francophone & Contributing Editor:

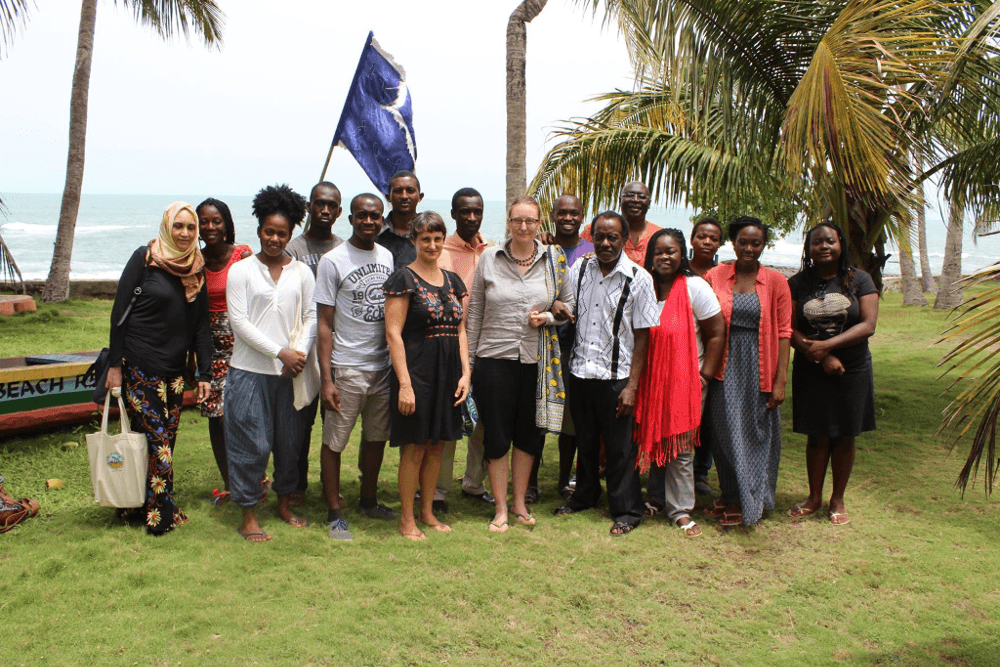

I was only lucky enough to meet Kojo Laing once. And I was late. It was in my mother’s village, Elmina, in the height of summer at the Caine Prize Workshop in 2015. Laing came across as a humble and effortlessly intellectual man. There was something quietly magical about him, as if he was tuned to a slightly different frequency to the rest of us. He talked to us about our writing and our work and didn’t mention his own great fiction, like Woman of the Aeroplanes (my favourite of his) or Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars (so ahead of its time), except to say he didn’t regret writing them and enjoyed all his own works.

He was wittily derogatory about mainstream publishers and the vagaries of critics, encouraging us to ‘Never listen to anyone!’ when it came to our writing. Which is something he did himself. Devoted to his fantastical visions and free of convention, Laing’s career was marked by really brave writing that mixed fantasy, African mythology and questions of the postcolony (the latter, especially, in Search Sweet Country) in entertaining and unexpected ways.

Unfortunately, I feel Laing never won the level of success his writing deserved in his lifetime. Some of his books are out of print, and he never quite managed to become a household name in Ghana or abroad. It’s a warning to all bookish people, and those who care about African literature, to take better care of our writers. But to write is to be immortal and—especially with his impressive oeuvre—there is infinite time for Laing to get the recognition he deserves.

Rest in Power, Pa Kojo

Tade Thompson, short story writer and the author of Making Wolf and Rosewater:

Kojo Laing is one of the unsung heroes of African fiction. His prose is poetic, and densely packed with strange juxtapositions and more ideas on one page than most writers use for several books. His use of language was masterful.

I had never heard of Laing until a friend introduced me to his work some years back. I could not believe his books were not already on the reading lists of literature courses. When I read Woman of the Aeroplanes it was clear that this writer loved elegant sentences and the myriad permutations and combinations of words.

If there is any silver lining at this moment it should be awareness of his work. Those who do not know him, particularly those with literary ambitions, should pick up his novels. Search Sweet Country is an amazing achievement. I hope a publishing house takes it upon themselves to reissue his books.

Wole Talabi, editor and short story writer:

For the last year or two, I have been helping to build a database of African speculative fiction. During my research into the earlier years of African science fiction I came across Kojo Laing’s short story ‘Vacancy for the Post of Jesus Christ’, which is a wonderful, surreal piece of allegorical science fantasy. In it, a golden wood lorry descends to earth and its driver, a bronze man who has just killed Jesus Christ millions of galaxies away, is searching everywhere, from courtrooms to mortuaries, for a replacement.

I found the story in the The Big Book of Science Fiction, edited by Ann and Jeff Vandermeer and published in June last year. I think it’s the only story by an African included in the collection, which in a way says a lot about how highly Laing’s work is regarded by other important writers and researchers in the field, even if it is not familiar to a wide audience.

For a long time, I was one of those who did not know of Laing and his work, and now that he has passed I feel a strange, general sense of loss, having come to his work so late. But I will honour him and his memory as best I can by seeking out more of his work and reading it, because if the rest of it is anything like ‘Vacancy for the Post of Jesus Christ’, which defies classification or understanding but is full of brilliant, unusual and fiercely original writing, I know I will not be disappointed. And I hope that, with time, a larger audience at home and abroad will join me in catching up with the work of a man who, by all accounts, was clearly one of Africa’s most fearless literary innovators and well ahead of his time.

Miriam Pahl, Africa Department, SOAS University of London:

Even though Achimota City and the world beyond have not developed the way that Kojo Laing imagined—we are not yet renting rooms in the sun, his Ministry of Fish has not materialised (even though Nnedi Okorafor imagines something similar close by, along the West African coast, in an alternative present) and termites are not building mansions for humans to live in—his literature may very well be called prophetic and avant-la-lettre.

If we believe all those voices telling us that African science fiction is a new thing, that science fiction is now finding a new home on the African continent, then Laing’s writing is not only futuristic but also from the future. Laing had imagined a future Ghana in the year 2020 (or rather just Achimota City, as Ghana and the continent have gone mysteriously missing in the first War of Existence) in his 1992 novel Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars, and therefore deserved the label ‘African science fiction writer’ back then. He also anticipated issues that concern us now more than ever, such as the balance between human beings and the environment, wars being fought ‘indirectly’, and the ‘externalisation’ of our minds and humanity into the digital space.

On another level, in his grotesque and absurd writing style Laing fights a different ‘War of Existence’ on the fronts of African literature. The first sentences of Major Gentl hardly make sense, and this continues through to the end:

Major aMofa Gentl was feared in Achimota City for his gentleness, since it was this quality that won the first war for the golden cockroach, the emblem of the city. […] The war was won against Torro the Terrible Roman, the only man in the universe who could stand both frontally and sideways at the same time, boof.

Boof indeed: considering this ‘non-sense’ in the realm of ‘the African novel’ as we know it from Achebe, Ngũgĩ & Co in the Heinemann African Writers Series, Laing performs the same—as he calls it in Major Gentl—‘disestablishmenticism’ that he ascribes to the characters of his novel. He pushes back against the imperatives of realism and seriousness that define the canon of the Anglophone African novel, as it has been established by the series and in the literature departments of Euro-American universities, and treads new paths instead, paths that have been taken up by contemporary writers today. In that sense, where Major Gentl won the second War of Existence in the novel, the war of existence for a more diverse African literature transcends the novel, as well as Kojo Laing’s life.

Geoff Ryman, author and senior lecturer at the University of Manchester Centre for New Writing:

The Hazy, Hurried Thoughts of a Westerner on the Death of B Kojo Laing

If some West African fiction reminds me of Henry James, then Kojo Laing sometimes reminds me of Dickens.

In Laing’s first novel Search Sweet Country, the city of Accra is a main character. This reminds me of Dickens’s use of London as a setting. As in Dickens, colourful, oddly-named characters crowd into the story, such as Mr ½-Allotey, Sally Soon and Ama Payday. Like Miss Havisham or Mr Micawber they have a touch of the fantastic, the grotesque and the humorous. If Dickens rejoiced in the vernacular, Laing insists on using local words … and making up new ones just to confound us.

Laing’s Woman of the Aeroplanes is unlike any other novel I have read. Unlike Amos Tutuola, with whom he is sometimes grouped, Laing is not necessarily drawing on folktales or traditional beliefs. The novel is like a satirical dream of his own life spent partly in Scotland, partly in Ghana, moving back and forth between impossible versions of both. It’s like a fever dream version of the diaspora experience … and of Africa being both immortal and invisible. Here, grasping for something similar, I turn to Japanese film director Hayao Miyazaki.

When I heard the news last week that Kojo Laing had died, I went directly to Ghana’s online newspapers, imagining that his death would be national news. I was dismayed to find nothing. I had just booked my flight and visa to Ghana so that I might interview both him and Jonathan Dotse (of AfroCyberPunk). It felt to me like the tragedy of all writers was being performed by a particularly deafening kind of silence. So I sounded off on the African Fantasy Reading Group on Facebook, which was bad form.

The JRB, in giving me the chance to contribute this piece, helped clarified my emotions and my view. Of course B Kojo Laing is slightly under-regarded in his own country. Prophets often are. He wrote too soon in ways that are not yet appreciated.

Too soon

The 1996 film The Last Angel of History (by John Akomfrah and written and researched by Edward George of Black Audio Film Collective) is a mightily influential film, credited with helping to establish the concept of Afrofuturism in people’s minds. But it makes no mention of Kojo Laing, even though Woman of the Aeroplanes had been published in 1988 and Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars appeared in 1992.

Ntone Edjabe, editor of Chimurenga, talked to me about that film as well as a BBC documentary on Afrofuturism, as part of the 100 Writers of African SFF series:

All of this [the two films] talks of SF as from the diaspora, the poetics of schizophrenia, all these alienated bodies … which is fine, but how the fuck is it that they miss Kojo Laing? I mean you don’t get more SF than that shit. Where Kojo Laing’s work is mentioned, all the critical work on it has been in relation to the literary buzz about African magic realism dah dah dah …

The terms needed to describe Laing’s work did not exist at that time – and probably still don’t. Even if Afrofuturism had become more established, better enabling the reception of his work, I don’t think Laing is a futurist of any kind. He’s not writing science fiction (unless you use SF so loosely it means any kind of fantastic literature).

His work was described as magical realism, and often still is. For me magical realism grows out of Latin America, a successful colonisation that wiped out most of the indigenous culture. The magic in magical realism does not have deep cultural roots nor is it particularly believed. The fantasy comes across as a kind of whimsy – the whimsy of the victors. It’s not a suitable term when you are dealing (respectfully I hope) with the current beliefs and traditions of people who held to them through the experience of colonisation. Even though they may be using those living beliefs to interrogate modernism or defending them against it.

In the Introduction to his 2013 novel Sacred River, Syl Cheney-Coker says: ‘I have made liberal use of my West African heritage, which is not be confused with that of writers grouped inside that intellectual humbug called “magic realism”.’

(… Possibly overstated.)

In a 1987 interview in Wasafiri with Adewale Maja-Pearce, Laing indicated that he was not doing something that was futurist, nor I think magical realist. Laing says he deals with the gap between traditional and modern experience. For him, the traditional is not necessary a good thing. The witch Adwoa Adde in Search Sweet Country finds that using her traditional powers is cutting her off from love, and confusing her about what is good and what is not. In the interview Laing says:

When I deal with the traditionalists in the book, I criticise them not necessarily in relation to anything external, but in relation to the fact that stagnation is there, and I would push this beyond what the average Ghanaian would find sensible.

So, at least to an extent, Laing regards the modern as a good, because it is allied with change. Much as he loves the traditional, it too must move. But I’m not at all sure I would go so far as to say that is what his fiction is about, or what it does.

Too difficult? Or are we reading in the wrong way?

Carolyn Slaughter in the Los Angeles Times review of Woman of the Aeroplanes for July 15, 1990 warned readers:

A word about the writing style: Until you become acclimated to it, it’s liable to bring you out in a hot sweat. It’s strong, original stuff, foreign and unexpected, like the first bite of raw garlic. Writing like this requires no passive act of absorption – you’re going to need energy and dedication to beat your way through the jungle of the prose […]

But it isn’t just the prose that is difficult. For me at least, there is something in Laing’s writing that resists interpretation.

Here is the plot summary of his short fiction, ‘Vacancy for the Post of Jesus Christ’:

A lorry descends from the sky to feed people in a famine. The truck seems to be made of a kind of wood that is also gold. A sign unfurls from the bottom of the truck, advertising a vacancy for the post of Jesus Christ. At the wheel is a giant black man made of bronze, who claims to have killed God. ‘I am the first evil galactic African bronzeman.’ He goes recruiting to the morticians to find his new Jesus and selects two dead people he may resurrect. He makes the local priest into his mindslave and the Father carries the two dead bodies … to a courtroom where the giant appears to be on trial, and then on to the buildings of government. SPOILER. In the end the truck ascends, leaving the bronzeman behind. He has shrunk, but only by two inches. On the truck, waving, are all the people the bronzeman has killed. One of them is Jesus Christ.

The scenes in the famine camp, the morgue, the courtroom and the government building seem to exist for structural reasons as much as anything else, moving from one venue to another. Some satirical points are made, but the story is no more about law or religion or how the rich and the poor clash than Alice in Wonderland is about royal privilege or the working of courts … or Freudian imagery, or a quest for a garden, or a parable about the confusions of puberty. Or whatever. Attempts to boil down Alice in Wonderland always seem too personal, too incomplete, or too full of agenda.

I get similarly depressed and impatient when someone tries to describe, oh, Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars as an ecological fantasy in which life takes revenge on colonialism or militarism. I get depressed at my own futile efforts to box in Laing or pin him down.

For me, you either get B Kojo Laing or you don’t – like Alice, like Miyazaki’s Chihiro, the story and the invention are their own meaning and justification. Endlessly inventive, I think improvisatory, true to some deep inner dream logic – Laing’s writing, I think, exists solely in its own terms. We don’t know what those terms are yet.

2 thoughts on “Rest in Power, Pa Kojo: Paying tribute to Kojo Laing”