1. Chinua Achebe, modernist

What might it mean to offer a suite of lectures on Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart within the domain of literary modernism?

I found myself confronting this question when, in August 2016, I proposed Achebe’s novel for inclusion alongside more established works of modernist fiction currently offered in the third year component devoted to modernism in the English Department at Wits University. After a brief yet spirited debate it was agreed that Achebe’s novel would stand alongside James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway.

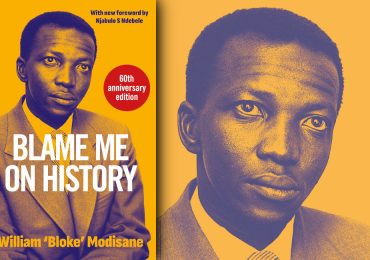

Yet Achebe’s inclusion bothered me even then, and it continues to bother me now. It felt strange to see Achebe’s name alongside those of Eliot, Woolf and Joyce. Achebe is more frequently (and at the expense of other African writers whose works preceded him such as Amos Tutuola, Peter Abrahams, The Dhlomo brothers, Thomas Mofolo and others) regarded as ‘the father of the modern African literature’. He is rarely—if ever—mentioned in summary accounts listing the names of the litany of mainly European, British, or American authors whose claims upon literary modernism are largely beyond question.

Things Fall Apart thus threatened to render strange a more familiar—perhaps even settled—mini-modernist canon. That this eventuality was probably itself a typically modern undertaking was not lost on me.

The irony haunted me for months.

2. (Re-)readings

Chinua Achebe was born on 16 of November, 1930 in the Igbo town of Ogidi in the South-Eastern sector of what was then the British Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. His well-known and widely celebrated novel, Things Fall Apart, was published by Heinemann in 1958, two years prior to Nigerian independence.

Yet Things Fall Apart is set in a precolonial Igbo village, Umuofia.

I find this curiously doubled historical provenance of Things Fall Apart fascinating. A peculiarly Janus-faced novel, it looks forward to a postcolonial Nigerian future while looking back to a precolonial Igbo imaginary.

When Things Fall Apart first appeared it bore a subtitle, ‘The Story of a Strong Man’. It is not hard to see why: the novel, which is divided into three parts, takes shape around the figure of Okonkwo—a powerful and hard-working yet violently flawed and ultimately tragic protagonist. Yet the story of Okonkwo’s rise, exile, and tragic fall seems surprisingly meagre, and Achebe trains as much—if not more—of his eye on the everyday life of Umuofia’s inhabitants and their customs: wrestling matches, communal feasts, marital occasions, religious rites, sacred rituals, and legal trials. Things Fall Apart is therefore as invested in Okonkwo’s fate as it is in sketching in and juxtaposing scenes derived from everyday precolonial Igbo life. At a mere 150 pages, it is slim enough to be a novella.

I first read Things Fall Apart as an undergrad at the University of Cape Town. Like many students, I suppose, I found Achebe’s references to yams, foo-foo, and kola nut curiously comical, and I was disappointed by what I felt to be its simplicity. Yet I also felt compelled to defend the novel against the words of a young German student who referred to it—and to African literature in general—as being quaint or naive. Her attitude, I felt, seemed patronising enough to caution me against my own adolescent literary prejudices.

Since then, I have taken greater pleasure in Achebe’s economy with words both English and Igbo—with the ease with which he handles and blends two seemingly incompatible linguistic and cultural currencies. I have come to appreciate the elegance of the novel’s three-part structure: details about Umuofia are only relayed to us from afar during Okonkwo’s exile in Mbaino in the novel’s second section, Achebe thus inviting us to wonder to whether the missionaries’ encroachment into Umuofia might have been inhibited had Okonkwo been present. I find myself lingering with curious fascination over Achebe’s descriptions of those elements of Igbo life that I had once dismissed as mere superstition: chi, egwugwu, iyi-uwa and ogbanje are now magical words ironically signifying the reality of magic and so-called magical-thinking itself within the rich cultural context of Igbo life.

As I reread Things Fall Apart again in preparation for this year’s lectures I find myself drawn to the figure of Ezinma, the daughter of Okonkwo and Ekwefi. In one particularly memorable scene Ezinma falls ill, an eventuality that leads the narrator to explain that she is believed to be an ogbanje child—one fated to die young because she is possessed by an evil spirit that repeatedly re-enters the mother’s womb in order to be born again. Ezinma’s connection with the ogbanje is broken when a medicine man convinces her to reveal the the location of her iyi-uwa—a magical object that has been buried and which links her to the ogbanje world.

Later, Ezinma is spirited away in the dead of night by Chielo, a priestess dedicated to the goddess Agbala. Terrified by what might befall her daughter, Ekwefi follows Chielo through the darkness to her hut deep in the woods. As she waits in the darkness she is surprised to find that Okonkwo, who had shown no sign of concern for the fate of his daughter upon Chielo’s arrival, has also made his way to the priestess’s hut. This scene captivates me less for the skilful manner in which Achebe generates an atmosphere of high tension, or even for the subtle manner in which it portrays Ekwefi’s anxiety or lends Okonkwo—a man of ‘action’—surprising emotional depth. Rather, I find myself wanting to know more about what has happened to Ezinma in Chielo’s hut. Achebe does not say. A few chapters later, we learn that Ezinma has become a beautiful young woman with many suitors and that she is bound for marriage.

And, with that, she vanishes from the story.

These details fascinated and delighted me, but they did not seem particularly germane to the question of Things Fall Apart’s relationship to modernism. So I decided to return to my initial fascination with the novel’s curiously Janus-faced historical outlook.

Janus: Roman god of gateways and doorways, a liminal, transitional figure that, like Achebe, looked towards an uncertain future and a similarly occluded past. But when, exactly, do the events depicted in the text take place?

3. Pedantry I: Missing Dates

In the novel’s final pages Achebe turns his attention to the mind of a District Commissioner who muses about writing a book that will be called The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger:

As he walked back to the court he thought about that book. Every day brought some new material. The story of this man [Okonkwo] who had killed a messenger and hanged himself would make interesting reading. One could almost write a whole chapter on him. Perhaps not a whole chapter but a reasonable paragraph at any rate. There was so much else to include, and one must be firm in cutting out details.

As an imagined ethnography housed within the fictional parameters of Achebe’s novel, The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger has peculiar literary currency. It is a fiction within a fiction—a literary example of mise-en-abyme—that raises serious questions about the nature of literary fiction on the one hand and colonial history on the other. The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger might also be usefully compared to Arthur Glyn Leonard’s similarly titled The Lower Niger and its Tribes (1906). This text, far from offering details of the colonial ‘pacification’, is really a peculiar ethnographic study of ‘The philosophy of the people as expressed in words, names, proverbs, and fables’.

The Lower Niger and its Tribes is nevertheless (and everywhere) sadly locked in a curious colonial double-bind: if Glyn Leonard repeatedly invites his readers to keep an open mind about the potentially shocking unfamiliarity of a West African culture and custom, urging them to withhold moral judgment in favour of recognising that it merely represents a different yet no less coherently-organised world-view, he also remains helplessly blind to his own prejudices. Glyn Leonard’s passing remarks about Roger Casement—an Irishman who worked for the British Foreign Office and who was honoured for The Casement Report (1905), which detailed colonial abuses in the Belgian Congo—typify this imperial double-bind. For if Casement represents a more admirable example of ‘our West African Administrators’ he nevertheless remains a colonial ‘[handler] of natives’ who represents a typically ‘European inability to see matters […] in the same light as the barbarian does’ (my italics).

Casement’s name is closely associated with Joseph Conrad—the pair met in the Congo in 1890—and it was during this time that Conrad drafted Heart of Darkness (1899). This novel, widely regarded as a classic of modernist literature, arguably succumbs to a similarly depressing imperial double-bind. The events depicted in Achebe’s novel occur well before Conrad announced himself on Modernism’s literary stage—and well before the establishment of the British Protectorate of Nigeria in 1901. It is almost as if Achebe wishes to get around the problems posed by imperialism and colonialism by getting before them. Using Glyn Leonard’s The Lower Niger and its Tribes as a real-world index for the District Commissioner’s fictional The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes Tribes of the Lower Niger, and subtracting Things Fall Apart’s scattered chronological markers from the year 1900, I manage to work out that events depicted in the novel take place roughly twenty-seven to thirty years before the turn of the century, that is, sometime between 1870 at the earliest, or 1879 at the latest. These dates are flexible and, more troublingly, fictional.

In my lectures, therefore, I resisted any temptation to claim that Things Fall Apart is set in the decade following the annexation of Lagos as a Crown colony in 1862. And while I spent a fair deal of time covering modernism’s relationship to imperialism and colonial expansion across Africa and Nigeria, I now wish that I had devoted less time to what could only ever have been a potted history, and more to a discussion of the nature and repetitive style of Achebe’s mode of narration. I would have liked to expand on the idea that repetition represents Achebe’s attempt to mimic the additive lexical patterns that are a key feature of narrative’s oral traditions. By artfully signalling his commitment to oral traditions, I might have argued, Achebe urges us to suspend our disbelief and to imagine that we are reading (or, rather, ‘overhearing’) one version of a story that has adopted a similar (but variable) pattern in the course of being passed down through generations by the word of many different mouths.

4. Pedantry II: ‘Modernism’

Clement Greenberg, Rita Felski, and José Ortega y Gasset have all regarded modernism as an self-critical, self-conscious aesthetic style: ‘the new art is an artistic art’ as Ortega y Gasset suggests in The Dehumanisation of Art (1968). Yet others have approached the question differently, even if they reached similar conclusions. In ‘The Metropolis and the Emergence of Modernism’ (1992), for instance, Raymond Williams regards modernism’s persistent ‘innovations in form’ as a consequence of ‘the fact of immigration to the metropolis’. If Williams equates modernism’s persistent formal innovations with the fact of immigration, this is because the modern subject is ‘liberated […] from their national or provincial cultures, placed in quite new relations to those other native languages or native visual traditions’. In this way, Williams suggests, ‘the artist and writers and thinkers of this phase found the only community available to them: a community of the medium; of their own practices’.

Later theorists would emerge to unsettle such assured foundational definitions. In ‘Modernism and Imperialism’ (1990), for example, Fredric Jameson questions ‘aestheticism and its ideological commitment to the supreme value of a now autonomous Art as such’ as being ‘part of the baggage of an older modernist ideology which any contemporary theory of the modern will wish to scrutinise and to dismantle’. Jameson’s interest in undoing older theories of modernism and modernity begins from the observation that modernist art rarely confronts its own association with imperialism or colonialism as directly as it might. Jameson wishes to know why European modernism appears incapable of confronting imperial and colonial leagacies that have haunted it since the earliest stages of its modernity. The answer that he offers is both complex and potentially damaging to anyone who may wish to foreground modernism’s imperial and, more crucially, colonial dimensions. This, Jameson explains, is largely because:

[…] colonialism means that a significant structural segment of the economic system as a whole is now located elsewhere, beyond the metropolis, outside of the daily life and existential experience of the home country, in colonies over the water whose own life experience and life world—very different from that of the imperial power—and unimaginable for the subjects of the imperial power, whatever social class they may belong to.

The invisibility or occlusion of colonial experience under the sign of an imperial modernity is particularly troubling. And it is perhaps this inability to properly see colonial experience that leads Simon Gikandi to argue, in Writing in Limbo: Modernism and Caribbean Literature (1992), that postcolonial literatures adopt a persistently revisionist stance in relation to categories such as modernism and modernity.

In spite of Jameson’s assumptions about the ‘unimaginable’ nature of colonial experience, a number of recent studies have returned to the question of modernity’s involvement with the imperial and colonial dimensions of a globalised modernity. Among these, Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker’s Geographies of Modernism (2005) avoids any attempt to define modernism conceptually or to set it within a bounded historical period and considered instead its varied geographical locations across the globe. In 2008, Rebecca L Walkowitz and Douglas Mao’s ‘The New Modernist Studies’ appeared in a special issue of PMLA, where they questioned the extent to which the term ‘modernist’ might be applied to non-Western literary works that, while seeming to share modernism’s stylistic traits, may not wish to be subsumed by such a patently ‘Western’ category.

The linkages between modernity and colonial experience are even more apparent in Walter Mignolo’s The Darker Side of Western Modernity (2011). According to Mignolo, modernity, modernisation and perhaps modernism itself are terms that include (while tending to obscure or ‘cover-up’) their involvement with coloniality, colonisation and colonialism. In much the same way that Ferdinand de Saussure has described the links between language and thought—with signifieds occupying the recto and signifiers the verso side of a sheet of paper—modernity is inseparably bound to coloniality. For Mignolo, then, ‘modernity’ arguably gives way to the modified expression, ‘modernity/coloniality’.

This is dry, complicated, theoretical stuff and, as I pore over the critical and theoretical tracts devoted to delineating modernism’s conceptual domain, I suspect that to accept the terms of any of these arguments would be akin to following Alice’s White Rabbit into a theoretical Wonderland from which I might never return. I have no desire, for instance, to take up cudgels with Aijaz Ahmad against Jameson’s argument that postcolonial literature is inevitably a form of national allegory; I balk, thirty or forty pages in, at Mignolo’s implicit Whorfianism.

Wasn’t Whorf debunked by Chomsky in the ’sixties?

I tinker with the idea of introducing my students to Homi Bhabha’s concept of the ‘postcolonial time-lag’ but, as I pore over pages of Bhabha’s notoriously abstruse and intractable theoretical language, I forget almost entirely my initial reasons for consulting his work. Far from spurring me on, Bhabha leaves me lagging far behind. Heavy-headed and blurry-eyed I look on blankly as his words begin to swim and slip across the page like schools of impossible fish.

I opt for a different approach.

5. Baudelaire and the Black Venus

In The Painter of Modern Life (1863), Charles Baudelaire coined the term ‘modernity’ to describe the ephemeral experience of urban life.

But I am more interested in the fact that Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (1857) contains a suite of poems allegedly inspired by his affair with Jeanne Duval, the Haitian-born actress and dancer whom he referred to as his ‘mistress of mistresses’ and his ‘Vénus noire’. Duval is also the subject of Édouard Manet’s painting, Baudelaire’s Mistress Reclining (1862), where Manet’s typically swift and rough style casts her as a curiously wooden figure. Set in awkward repose upon an indigo chaise longue, her skirts billow absurdly across the frame. An indigo fan rests idly against her left hip. Her right hand is disproportionately grotesque.

‘She looks like a mushroom,’ I think.

But I also think about Duval’s South African precursor, Saartje Baartman, the so-called ‘Hottentot Venus’ spirited from the Gamtoos Valley by Hendrik Cesars and William Dunlop and displayed—‘from TWELVE ’till FOUR o’Clock and for an admittance fee of 2s.’—on a Piccadilly stage. And I remember Willie Bester’s welded, scrap-metal sculpture of Baartman—all nuts and bolts, wheels and cogs, the jagged wastage of coloniality and capital—looming over me and over all those privileged enough to pass, ghostlike and ephemeral, through the Chancellor Oppenheimer (née Jagger) Library at UCT.

Like some terrible, mute chastisement demanding an answer.

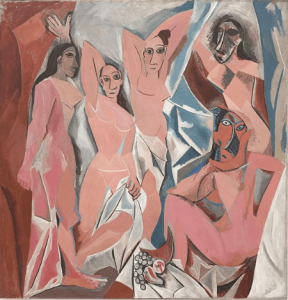

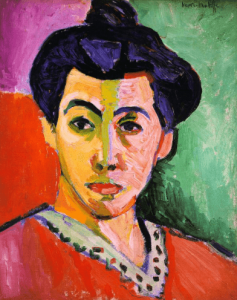

[Editor’s note: click here for a recent article on art on UCT’s campus.]I recall other, less personally chastening examples of European modernism’s involvement with far-flung margins of European empire. I recall Ezra Pound’s ‘Exile’s Letter’, a translation from the Chinese poetry of Li Po; Ernest Fenollosa’s preoccupation with Chinese ideograms; Yeats’ preface to the English translation of Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali; DH Lawrence and Malcolm Lowry in Mexico; Leonard Woolf in Sri Lanka (née Ceylon). But it is Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and Henri Matisse’s Portrait of Madame Matisse (1905) that arguably strengthen the linkages between modernism and African art. Both paintings were allegedly inspired by Picasso and Matisse’s encounter with an African mask initially procured by the French painter Maurice de Vlaminck and later purchased—and shown to them—by André Derain. These scattered memories evoke a material record that validates Eric Hayot’s (2010) suggestive observation that, ‘at the so-called origin of European modernism, the foreign has already inserted itself’.

Yet they do little to convince me that I will be able to persuade my students that Things Fall Apart is an exemplary work of modernist literature.

I press on, regardless. In my lectures I unpack and unpick scholarly definitions of the term ‘modernism’. I show my students the aforementioned modernist paintings, lingering on the image of Laure, the black servant depicted in Manet’s Olympia (1865). I forge tenuous analogies between Things Fall Apart and modernism’s stylistic and ideological repertoire: I transform Okonkwo into an alienated subject; I wonder aloud about how Achebe’s stylistic appeal to oral traditions might render uncertain our assumptions about authorship, and whether these uncertainties might be akin to modernism’s preoccupation with fragmented or multiple forms of authorial perspective; I discuss Emily Hyde’s ‘Flat Style: Things Fall Apart and its Illustrations’, published in PMLA in January 2016, which compares illustrations by Dennis Carabine to those of Uche Okeke in order to foreground Achebe’s distinctively modernist style.

In these and other ways I hope to suggest—if not to demonstrate—the entanglement between modernity and coloniality: to reveal the foreignness occluded for so long yet always there, hidden in plain sight, at the heart of empire.

Yet at the last, I feel that none of this is quite enough. To paraphrase JM Coetzee’s remarks about the poetry of Paul Celan, modernism—as a term, a category—stands in our way like a tomb.

In the end I find myself staring at digital images of Paul Gauguin’s painting, ‘Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?’ (1897). Begun in Tahiti during a period of crushing tragedy and despair in Gauguin’s life (he had lost a daughter and, mired in debt, allegedly planned to commit suicide upon the painting’s completion) it seems to glow with more colour than seems possible. I have a particular affinity for Gauguin’s title, especially now, with my lecture-series expiring in the wake of a ‘decolonial’ moment—and the ongoing review of various curricula at South African institutions of higher education—that also seems typically and disorientingly modern. We are undertaking, in the immediacy of the here and now, our own Nietzschean ‘transvaluation of all values’.

But what are we doing? And where are we now?

‘Now’: a point at which things seem always to be falling apart.

- Simon van Schalkwyk is Academic Editor and lecturer in the English Department at Wits University

Index

Authors

- Peter Abrahams

- JM Coetzee

- The Dhlomo brothers

- Malcolm Lowry

- Thomas Mofolo

- Amos Tutuola

Art

- Sarah Bartmann by Willie Bester

- Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? by Paul Gauguin

- Baudelaire’s Mistress Reclining by Édouard Manet

- Olympia by Édouard Manet

- Portrait of Madame Matisse by Henri Matisse

- Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso

Artists

- Dennis Carabine

- André Derain

- Uche Okeke

- Maurice de Vlaminck

Books

- Les Fleurs du Mal by Charles Baudelaire

- The Painter of Modern Life by Charles Baudelaire

- Geographies of Modernism by Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

- The Casement Report by Roger Casement

- Writing in Limbo: Modernism and Caribbean Literature by Simon Gikandi

- Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

- The Lower Niger and its Tribes by Arthur Glyn Leonard

- The Darker Side of Western Modernity by Walter Mignolo

- The Dehumanisation of Art by José Ortega y Gasset

- Gitanjali by Rabindranath Tagore

- Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

Essays

- ‘Flat Style: Things Fall Apart and its Illustrations’ by Emily Hyde

- ‘Modernism and Imperialism’ by Fredric Jameson

- ‘The New Modernist Studies’ by Rebecca L Walkowitz and Douglas Mao

- ‘The Metropolis and the Emergence of Modernism’ by Raymond Williams

People

- Saartje Baartman

- Hendrik Cesars

- William Dunlop

- Jeanne Duval

- Leonard Woolf

Poems

- The Waste Land by TS Eliot

- ‘Exile’s Letter’ by Ezra Pound

Poets

- Paul Celan

- Li Po

- WB Yeats

Scholars

- Aijaz Ahmad

- Homi Bhabha

- Noam Chomsky

- Rita Felski

- Ernest Fenollosa

- Clement Greenberg

- Eric Hayot

Topics

- African literature

- Belgian Congo

- Colonialism

- Modernism

- Nietzsche

- Nigerian independence

- Tahiti

- Whorfianism

_____

Images: Fang Mask, Rowan University/Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Wikipedia Commons/Green Stripe, HenriMatisse.org