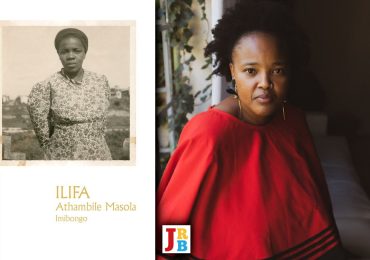

Recently published biographies of Pixley ka Seme and Charlotte Maxeke reveal how women’s histories become insignificant back roads in the geography of memory, writes Athambile Masola.

The Man Who Founded the ANC: A Biography Of Pixley ka Isaka Seme

Bongani Ngqulunga

Penguin Random House SA, 2017

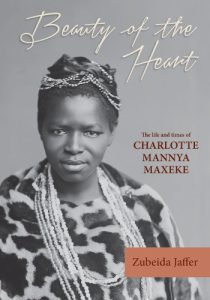

Beauty of the Heart: The Life and Times of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke

Zubeida Jaffer

Sun Media, 2016

Dr Pixley ka Seme Street—formerly West Street—is one of the major roads in the Durban central business district. Less than three kilometres away is Charlotte Maxeke Street, a tiny, obscure road tucked away from the bustle of the city. I didn’t even know there was a street named after Charlotte Maxeke until I discovered it on a recent trip to Durban; as it turns out, there are two more, in Bloemfontein and Pretoria, equally obscure.

Street names are a big deal in South Africa, and this is especially so in Durban, as it is the only one of South Africa’s prominent cities to have done a complete clean-out of colonial names. To the cynical eye, the streets named after Seme and Maxeke appear to be a deliberate representation of what their respective legacies mean, a metaphor for how their memory is valued in our national imagination. Dr Pixley ka Seme is busy and bustling, while Charlotte Maxeke is a back road one is only likely to stumble upon when lost. Even the geography of the city, then, mirrors how memory is constructed in South Africa’s historiography.

When Bongani Ngqulunga’s biography of Seme, The Man Who Founded the ANC, was launched recently, I was taken back to the streets of Durban. I started reading Seme’s story and began to ask myself questions. It seemed odd, for example, that Seme and Maxeke’s stories are presented as parallel narratives that only intersect in 1912, when Maxeke attends the launch of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC or Congress, the forbear of the ANC) as the only woman present. I would like to imagine that, as the founder of the SANNC, Seme would have crossed paths with a woman like Maxeke well before 1912. Even though Maxeke was older (there are disputes over her year of birth), they had both studied in the United States, which placed them in the unique network of the educated elite of their time, and they had both been influenced by the work of WEB Du Bois. Maxeke returned to South Africa in 1901; Seme returned, via Oxford, nine years later. Seme established the newspaper Abantu-Batho, while Maxeke married Marshall Maxeke, the editor of Umteteli waBantu, which she is known to have contributed to. Given the burgeoning nature of the black press at the time it is not impossible to imagine that the Maxekes and Seme would have interacted and crossed paths regularly. In short, while reading Seme’s story in The Man Who Founded the ANC, I began to insert Maxeke’s story within it. It seems odd to write about Seme as though he had never lived in proximity to her, politically and geographically.

By contrast, in Maxeke’s biography, Beauty of the Heart: The Life and Times of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke by Zubeida Jaffer, there’s an entire section dedicated to Seme. I had been quite delighted when Jaffer’s biography was published, a year before Ngqulunga’s. But it was an empty delight. It reminded me how its subject remains an obscure figure in South Africa’s memory, and how the history of women in our country generally remains consigned to the back roads.

Writing Seme’s story without a mention of Maxeke, as Ngqulunga does, raises suspicions about the current, general call for more, ‘decolonialised’ stories about our past. If all we are offered along these lines is a flattened narrative—one which, for example, does not show the full range of Seme’s contemporaries, who could have been both men and women—this would suggest there isn’t enough space for all of our stories in our history, no matter how decolonised it becomes. Ngqulunga writes about Seme and women by writing about Frances Xiniwe, Seme’s wife, who cuckolds him unceremoniously a year into their marriage, or Princess Lozinja Dlamini, who is suspected to be Seme’s lover because of a son, Zwangendaba George Seme, whose name, according to Seme’s daughter, was ‘because the first news [Seme] had of his birth was from others’. There is also Queen Labotsibeni Nxumalo, who supported Seme financially when he established Abantu-Batho.

What would it have meant for us to read that Seme may have also interacted with Maxeke, Sibusisiwe Makhanya, Adelaide Tantsi and Nokutela Dube—and as his contemporaries, rather than as his wives and lovers? It seems odd that despite the relationship Seme had with John Dube there’s no mention of him interacting with Nokutela Dube, who played significant role in establishing the Ohlange Institute, even travelling with her husband while fundraising for the school. What if women were included—even recognised as being present—when writing about South Africa’s foundational moments?

I choose Maxeke quite deliberately because, like Seme, she was the founder of a movement, the Bantu Women’s League (BWL), in 1918, as well as being instrumental in the establishment of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in South Africa. The relationship between the BWL and Congress was a fraught one, especially considering the fact that women could not be members of the latter, merely being called upon to provide hospitality for the men at gatherings. However, there is evidence from Nontsizi Mgwetho and Maxeke’s writing that during Sefako Makgatho’s tenure as president of Congress in 1920, its internal strife spilled over into the BWL’s affairs, which forced Maxeke to respond with a critique of Congress in a letter she wrote in Umteteli waBantu. In the letter she refers to the weak leadership under Makgatho:

uMongameli we Congress yase South Africa jikelele wayekala malunga nezenzo zenkokeli zase Johannesburg ekwenzeni kwazo izinto nezigqibo ezintweni ezinkulu ngapandle kwake engazazi yena, pofu enguMongameli (womlomo)?

(The national president of the ANC was complaining about the leaders in Johannesburg who made decisions about major issues without his knowledge as though he were just president by name.)

Being a man of the papers, Maxeke’s political work would not have gone unnoticed by Seme, even if, as Ngqulunga suggests, he withdrew from political life to focus on practicing law, and on establishing Abantu-Batho and the Native Farmers’ Association during the 1920s. The women were there; their organisations were interacting with the men’s organisations; their impact on our history is clear to see in the source texts; but they don’t make the authoritative secondary treatments, the histories and biographies that tell us who we are and where we come from.

In spite of the erasure of the women who could have been Seme’s contemporaries, Ngqulunga’s work is successful in painting a more nuanced picture of the hero of the ANC, who was ‘wrecked by the extravagance of his own genius’, as RV Selope Thema says of him. Upon discovering what a ‘hot mess’ Seme was, I am no longer surprised by the ANC’s loyalty to its current president. It’s not simply that the ANC is no stranger to scandal, it’s that scandal is its inheritance, the result of having a founder such as Seme, whose ethos lingers in its current incarnation.

Moreover, we need to regard the nostalgia that harks back to a ‘respectable’ ANC, to an organisation that ‘fought for the people’, with a greater degree of suspicion than we have in the past. Has such an ANC ever existed? Seme’s business exploits swindled poor black people out of their money; he was seen as an autocratic leader; he fell out spectacularly with his mentor and one-time guardian, John Dube; and he lied about getting honorary doctorates from Howard and Columbia Universities.

By contrast, Maxeke who seems to have been without fault. The image of her as a dutiful wife (who could not have children) who served her country without ever setting a foot wrong is unfortunate. Perhaps, I find myself imagining, she patronised women who were not in her class or as educated as she was. Or perhaps she was a bully or an alcoholic. I would rather a realistic image than one that suggests she was beyond reproach, because sainthood entails its own kind of erasures. But even SEK Mqhayi’s poem, ‘Umfikazi uCharlotte Manyhi Maxeke’, written upon Maxeke’s death, would have us believe that she was exceptional:

Stand up women

The scraper has shifted;

The one who removes refuse.

Gone is the one who has been building a home,

Removing the idle and the drunkards;

Sending home those who like to be away from home;

And those who travel without purpose come home.

The foundation stone of Ethiopia!

Stand up women!Shukumani bafazi

Ushenxil’ uMamarhixirhixi;

Ufinyis’ amagruxu.

Ushenxil’ okad’ esakh’ umzi,

Egutyul’ irhanga namanxila;

Egodus’ amahilihil’ agoduke;

Kubuy’ amadungudwan’ emazweni.

Itye lesiseko seTiyopiya!

Shukumani bafazi!

You can be a ‘foundation stone of Ethiopia’, and get an occasional mention around the various cities that your legacy helped liberate. Conversely, as a man, no matter how flawed and corrupt you are, not only will your misdeeds attract very little outrage, but your name will sing along a thoroughfare that runs from the hills to the sea. To put it bluntly, Seme’s prominence in relation to Maxeke’s illustrates how history and current discourse prefer the stories of men.

In reading Seme’s biography alongside Maxeke’s, I am reminded of feminist scholar Nomboniso Gasa’s words, which I feel it is necessary to quote at length:

Sometimes significance lies not in the absence/presence, silence/speech, but in the actual ways in which we read the historical documents, listen to the meta-narratives and pay attention to the details of history, including those which do not fit snugly into those long used, tried and apparently tested boxes that are our analytical tools. Most importantly, the question is how we read, reconstruct the archives and the texts, listen to the narratives and develop the analytical tools and framework we find of greatest analytical power.

While we unearth our historical narratives, and write our histories and biographies, we need to be aware of the silences and erasures that leave some of us with more questions than answers. Not finding the intersections so can only mean we’re following the wrong roads.

- Athambile Masola is writer, blogger and former Mandela Rhodes Scholar. She is currently working on a PhD on Noni Jabavu’s memoirs and teaching at the University of Pretoria. Follow her on Twitter.