… I have always resented being dominated. I resent being dominated by a man, and I resent being dominated by white people, be they man or woman. I don’t know if that is being politicised. It is just trying to say, ‘I am human. I exist. I am a complete person.’

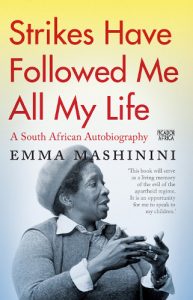

Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life: A South African Autobiography

Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life: A South African Autobiography

Emma Mashinini

Picador Africa, 2012

The inspirational trade unionist and political activist Emma Mashinini passed away at the age of 87 recently.

Mashinini was regarded as the doyenne of the trade union movement in South Africa. She served as a shop steward on the National Union of Clothing Workers (NUCW), was a founder of the South African Commercial, Catering and Allied Workers Union (SACCAWU), and was deeply involved in the establishment of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 1985. She was also an active member of the ANC from 1956.

Mashinini’s memoir, Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life, originally published by The Women’s Press UK in 1989 and republished by Picador Africa in South Africa in 2012, is a seminal work of South African autobiography. In it, Mashinini describes how she was detained without charge for six months in 1981, under section 6 of the 1967 Terrorism Act. She spent most of her detention in solitary confinement, and was released without being charged.

During her time in prison, Mashinini experienced the most harrowing torment of forgetting her own daughter’s name.

‘I struggled and struggled,’ she writes. ‘I would fall down and actually weep with the effort of remembering the name of my daughter. I’d try and sleep on it, wake up. I’d go without eating, because this pain of not being able to remember the name of my daughter was the greatest I’ve ever had.’

This excerpt from Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life illustrates the great sacrifices Mashinini made for her country.

~~~

I had the Bible to read, and the stories Tom had brought me, the radio, and the newspapers which I would have to destroy when I’d read them. It was so much more than at first, when it was only me. But somehow the one thing that should have brought me the most happiness instead brought me the most pain.

It was a picture of my grandchildren. I was excited to see it at first. It fell out of the books Tom had brought me. But afterwards, when I looked at the picture, it seemed as though those children were talking to me and saying, ‘Granny, what are you doing here?’ You know what it is to be a grandmother. It’s a very important thing. I became very anxious and I was ashamed to look at that picture. I put it beneath the blankets and slept on top of it, and when I did that it was as though I was squeezing the life out of my own grandchildren. I didn’t have anywhere to hide them. I didn’t want to destroy this picture, but at the same time I didn’t want to look at it because it hurt me. Their eyes were so pressing, as though asking me what I was doing there. And I was thinking about my family, day in, day out. I didn’t know what my children were doing or what they were thinking about this whole thing. They must be wishing for me to come home.

One day, thinking about my children – Molly, who was in Germany, my grandchildren and Dudu, who was in New York – thinking about their faces, and putting names to them, I could see my second-youngest daughter’s face and I wanted to call her by her name. I struggled to call out the name, the name that I always called her, and I just couldn’t recall what the name was. I struggled and struggled. I would fall down and actually weep with the effort of remembering the name of my daughter. I’d try and sleep on it, wake up. I’d go without eating, because this pain of not being able to remember the name of my daughter was the greatest I’ve ever had. And then, on the day when I actually did come across the name – this simple name Dudu or ‘Love’ – I immediately fell asleep, because it was such a great relief. But that was after days of killing myself to remember my own child’s name.

I didn’t know anything about the psychological effects of trauma. These are things I’ve only learned about since coming out of hospital. I thought instead that I was going mad, really going mad. And I was fighting very much against it because now I could read in the newspapers that people were going into psychiatric hospitals and I didn’t understand that you could go mad from being arrested. I just thought I was sick.

It’s only now, after years, that I feel I want to speak about this effect of being in detention. Not to talk about it is to deprive a number of people who will come up against it for the first time without knowing what their expectations should be. This is what the system

wants. The day I was released I was told, ‘You mustn’t discuss your detention with anybody,’ and I was obedient. I was afraid to speak about it in case it would leak. I did not want to go back to where I had been.

After visits from my family or friends I felt restored. It gave me more strength than ever before. So you can imagine what happens to people who do not have anyone to visit them. I think this was why I went so wild and excited to see those two young ladies who had come to visit Sisa. But with that there was the guilt. There was a song that was sung on the radio: ‘Every time you go away, you take a little bit of me with you …’ something like that. And I thought: I’ve been going away all my life. I’m a traveller. I’m always going away and now here I am in prison. It means that I have again found myself to be a nuisance in my family. I’m always causing them pain by going away. All I could hope for was that they understood that I had not committed any crime. I hoped I had not done anything to offend them. I worried about my friends. I thought: are they going to receive me when I come back?

In prison you are anxious and concerned about everything. You kill yourself about being there and what’s going to happen tomorrow, and all that, and you look forward to your outings – to the doctor, to visitors and to the interrogations.

And then, one day, bang – the interrogations just stopped. That was it, no word, nothing about why. And I missed them. I thought once again that I was going to be sitting in that room all by myself. I didn’t think I knew myself any longer. There was no mirror. It’s odd what happens when you don’t see yourself in a mirror for such a long time. You don’t recognise yourself. You think: who am I? All I had to recognise was a jersey that had been sent to me by a friend. But I didn’t know any longer how to recognise myself.

Ema Mashinini from Afravision on Vimeo.

2 thoughts on “In honour of Emma Mashinini: An excerpt from Strikes Have Followed Me All My Life”