All that is buried is not dead.

—Olive Schreiner, The Story of an African FarmAnt swarming City

City full of dreams

Where in broad day the spectre tugs your sleeve

—Charles Baudelaire

On a still, cool day in the east of a city by the sea, three sounds only: a bulldozer’s engine, a forgotten song, a canon that tells the time.

Behind the bulldozer, a sign: Luxury Mall Coming Soon …

—What Remains, Part 1

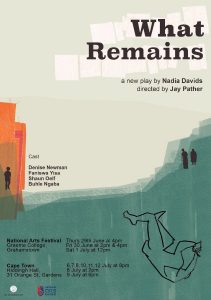

What Remains is a play about slavery and the haunted city, about ghosts and property developers, about archives and madness, about history, memory and magic, about paintings, protests and the now.

What Remains is a play about slavery and the haunted city, about ghosts and property developers, about archives and madness, about history, memory and magic, about paintings, protests and the now.

For the last few years I’ve been reading and thinking about slavery at the Cape. Neither the reading nor the thinking has been easy; it is a history full of unimaginable violence and unresolved sorrow. And unresolved histories have a way of making themselves known—‘the spectre tugs at your sleeve’, wrote Baudelaire, ‘in broad day’.

Cape Town’s dark beginning has cast a long and chilling shadow on its present: the morphing of slavery into colonialism and later apartheid has made it a city where, famously, natural beauty exists in stark contrast to deep and abiding disparity. And it’s a disparity that not only narrates a terrible history but also allows for a certain kind of protected ‘unknowingness’: it is possible to be of and from this place and not have to negotiate its past, not have to recognise its present. It is possible to do that until the past erupts and demands to be listened to.

The play is about an instance of rupture and reckoning and, though it grew to become about the moment we find ourselves in in South Africa now, it did not begin with a new generation of protests and protesters. It began, instead, with a generation long since passed. It began with a burial site.

I first began writing it at the end of 2014. At the time I thought I was working on a novella, a text about Cape slavery, loosely based on the uncovering of the graveyard at Prestwich Place in Cape Town where, in 2003, a corporate real estate development famously, unexpectedly, struck an eighteenth century burial ground—one of the largest ever to be unearthed in the Southern Hemisphere. Nearly 3000 bodies were accounted for, from babies who were a just few weeks old—the children of slave washerwomen—to men in their late sixties. It was, by any estimation, an astonishing turn of events.

The response in Cape Town was immediate and polarised: the property developers wanted to continue building, heritage managers and archaeologists prioritised a scientific examination of the remains (important data could be drawn from the bones, the material traces held answers, frustrating gaps in archival research could be closed) while an alliance of community activists claiming descendancy from those buried insisted on the immediate re-interment of the bones. They felt (understandably) that to examine the bones, to pick them over, would be to commit violence afresh on bodies that had in life been subjected to unforgivable cruelty. ‘Stop robbing the graves!’ cried someone at one of the first community meetings¹, and another, ‘I went to school at Prestwich Street Primary School. We grew up with haunted places; we lived on haunted ground. We knew there were burial grounds there. My question to the City is, how did this happen?’²

I was in Cape Town when the bones were discovered but I didn’t pay it as much attention as I might have. I’m not sure why, because it was an extraordinary drama in which battle-lines between competing values were drawn and insisted upon; lines between memory and history, the material and the immaterial, spirituality and science, the living and the dead. Over a decade later, I understand that moment as telling us not only about the faultlines of a post-apartheid city but also as a prophecy, a warning of just how deep our difficulties lie.

By 2014 I’d been living, for a decade, outside of South Africa. Each trip home (I returned frequently, sometimes several times a year, for work and family) was always made up in equal parts of nostalgia, longing, astonishment, love, anger and worry. Distance from home can be a strange thing: it intensifies the differences, the specificities of a place, it invites constant comparison, but it also blunts a deep, quick understanding of what is happening. I’m not sure anymore if anyone living outside of a place can ever really take its temperature; I missed certain things, certain developments, I noticed others … In a country like South Africa, where the national political life lurches with disorientating speed, it’s hard to keep track. When I left in 2004 I’d been working on and off at the District Six Museum for three years. It’s difficult to imagine now, but back then the conversation around land redistribution or compensation was not a matter of ‘if’ but ‘when’ and ‘how’. It wasn’t a radical conversation, it was a centrist one; it was understood as a reasonable series of steps that should be taken to rectify past criminality and ensure an equitable and functional future for the country. The dialogue between government and activists and NGOs around the issue may have been at times thorny, enmeshed in bureaucracy, and the distance between action and execution may have been frustratingly slow, but there appeared a broad moral and political agreement on what should happen. The gentrification of Woodstock and the Bo-Kaap had already begun, of course, but it wasn’t moving at the dizzying speed it is today: there was a sense then that a course correction was still possible; that an unravelling of the mess of past iniquity was within reach. There were instances of residents being driven from their homes, but those were unusual stories recited with horror, not resignation. There were no Temporary Relocation Areas like Blikkiesdorp, no reanimation of the old story of Forced Removals: You may have lived here for generations but this is not your home, leave now, here is a letter, we will move you to another place, far from here and what you know.

At some point that centrist conversation was moved irrevocably to the margins of the far left. I’m not a political analyst, I’m still not sure how this happened, but what I did know was that the city had re-choreographed an old dance and that we all knew the steps. A friend described that early noughties decade as containing all the foggy disassociation that comes after a night of euphoric celebration; ‘We were hazy,’ he said, ‘sleepwalking … no wonder these kids talk about wanting to wake us.’

As a writer, I wanted to circle in close to the city of my birth, write about its brokenness, its survival, but also I wanted to close one eye, obscure the location and create an unspecified landscape where each character’s voice borrowed from different times and places. It was to be both of and not-of Cape Town. The characters, The Healer, The Archaeologist, The Chairman (now Chairwoman), The Student and others came quickly, easily, but there was something about the form of the text that wasn’t quite working. I began to understand that it needed something else, required something else, and that something was live performance.

I’ve worked for a long time with the idea that performance and memory are intertwined, that they are each other’s echo and that no other art form is as uniquely placed to evoke memory, to represent it, to bring it into a conversation with the present. This is partly driven by the liveness of performance, by its capacity to disappear, but also because its very immateriality, its lack of durability, allows for a profound psychic interface between itself and memory. Both performance and memory are forms of storytelling that lend themselves to the communal. A play is not only collaborative in its making but in its viewing; the communal experience of watching a play is an important, ancient activity that binds us, that creates a fleeting community, that invites us all to bear witness at what is unfolding before us. In the staging of this work, Jay Pather places the audience in two rows, facing each other: in his director’s notes he explains the staging; ‘Looking across the room at a row of spectators watching like you, histories playing out, you may identify a perpetrator of catastrophe […] (or) on the opposite bank of spectators the possibility of an ally.’

This kind of precise thoughtfulness is of the (many) reasons I’ve always admired Jay Pather’s work. That and the seamless yet provocative way he forges connections and relationships between landscapes, the body, place and agency, the way he uses beauty to disrupt and challenge comfort. I approached him with the text, hoping that he would be interested in creating a performance piece from it. To my delight, he was. We decided early in our conversations that in addition to actors, the piece needed a dancer, a figure able to evoke the mysterious, the ghostly, a body that could hold history and tell its stories, narrate the unsaid, speak the unspeakable, that there were some histories—and slavery is one of them—where text is insufficient. It is only the body that knows, remembers, can tell.

During our initial workshops, I reworked the beginnings of the novella, dividing it into twelve-part performance text. (The twelve parts a nod both to the division of time in a year and day and to John Berger’s Economies of the Dead.) As the process unfolded, Pather transformed The Narrator, the figure who watches, observes, notices, tells, into The Student, creating a performative link with 2015’s student protests, one that suggested an intergenerational conversation and brought the play sharply into conversation with the now.

In watching this play being made, I was reminded of the collaborative nature of the theatre and how that collaboration shifts the primacy of a text and makes it just one of many components. The rest, the direction, the scenography, the choreography, the videography, the performers, each art form and artist brings their creativity, the weight of their experience, their own history of work, of life, to bear on what we are making, together. For a writer, this is thrilling, this is daunting: what was once on the page will spring, suddenly, into a different life. This is especially true when the cast takes up the text and the directorial vision and infuses it with new meanings: Denise Newman, Faniswa Yisa, Shaun Oelf, Buhle Ngaba move lightly, furiously, precisely, wildly, among the bones and the books of this story. They stand on burial grounds and talk on stoeps, they hear old songs and dance new steps, they argue about history and memory, they see the dead, they chastise the living even as they try to protect them, they speak, they reason until reason itself gives way, they enact archetypes even as they dig deep into the intensely personal dimensions of each character. It has been an immense privilege to watch them and Pather work together.

In early email correspondence, Pather wrote that the play is, at its core, ‘about “disruption”: the play understands disruption to be historic and deeply lodged in memory and in bone. When the bones are found, when they are disrupted, it is a topographic and geological disruption of earth that in turn becomes a metaphor for the necessity of breaking ground, of opening surfaces to allow truth to emerge. This energy of slippage and seepage connects with the student disruption and the taut, episodic structure—the twelve parts—as it tries to contain these impending disruptive moments until it too gives way.’ I would add that slavery itself is about extreme disruption; it is about rupture from place, it is about being snatched from one way of being and dragged into another. It is a radical remaking of time; the breaking of continuity and the construction of a terrible and eternal boundary between then, the life before, and now, the life after.

Towards the end of the piece, a group gather to lay claim to the bones, to rescue them from where they have been stored; they come with fire and dance and anger and chanting, and The Archaeologist says to The Healer ‘This cannot be the answer’. She replies, ‘It’s not an answer. It’s an old, old scream.’

There are no answers in this piece, only questions, only expressions about the relationship between then and now.

Postscript

As I write this, we are just a day away from leaving for the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown. It is Eid morning and I am sitting in my parents’ house while the smell of everything that is good in the world is floating up from the kitchen. It is the first Eid I have been home for in twelve years and it occurs to me this very Cape morning, as the rhythms of the day play out—a holiday celebrated on these shores for close to 400 years, that came here through slavery—that I cannot imagine What Remains holding quite the same meaning in any other city. I cannot imagine that strange mesh of feelings—sorrow, relief, rage, biting humour, disbelief, terror, wonder—present in the room as I watched the cast rehearse, manifesting in quite the same way anywhere else. I say this not because I want to speak of a people of one place laying possessive claim to the stories of that place (ownership between people and stories exist, but not the way we think: most of the time it is we who are in the grip of a story, not the other way around) but because there is something important about knowing the story that, from its first telling and at every retelling, has shaped the city you call home. There is something important about understanding what kind of place you come from, about being yanked from protected unknowingness, from the safety of sleep into being alive to the stories of your dead. It is, is in some sense, the least the living can do.

- What Remains played at the weekend at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown, and will play in Cape Town from 6 to 12 July; find more information on Facebook

- Nadia Davids is an award-winning writer who works across a range of forms: plays, articles, short stories and screenplays. Her theatre works, including the well-known At Her Feet and Cissie, have been staged in South Africa and abroad and her writing has appeared in various newspapers and anthologies. Her debut novel, An Imperfect Blessing, was published in 2015.

Footnotes:

1. Nick Shepherd, ‘Archaeology dreaming Post-apartheid urban imaginaries and the bones of the Prestwich Street dead’, Journal of Social Archaeology, 2007, p. 8.

2. Antonia Malan, 2003, p. 5 in Ibid.

References:

Henri, Yazir and Heidi Grunebaum, ‘Re-historicising Trauma: Reflections on Violence and Memory in Current-day Cape Town’, paper presented at the Direct Action Centre for Peace and Memory, Cape Town, South Africa, 2005. Available from: www.medico.de/download/report26/ps_henrigrunebaum_en.pdf (accessed 27 November 2011).

Jonker, Julian David, ‘Excavating the Legal Subject: The Unnamed Dead of Prestwich Place, Cape Town’, Griffith Law Review 14, 2, 2005, pp. 187–211.

Shepherd, Nick, ‘Archaeology dreaming Post-apartheid urban imaginaries and the bones of the Prestwich Street dead’, Journal of Social Archaeology, 2007.

THANKS FOR NEWS