Swing Time

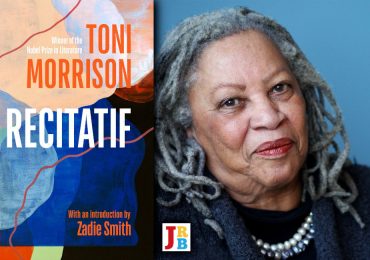

Zadie Smith

Penguin Books 2016

Behold the Dreamers

Imbolo Mbue

HarperCollins 2017

1.

Zadie Smith’s new novel, Swing Time, which takes its title from the 1936 film starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, is in many ways an ode to the tap dancing movies of Hollywood’s Golden Age. The novel takes place alternately in the 1980s and the mid-2000s, and is the story of two childhood friends whose lives twist apart. Smith deals thoughtfully with themes such as cultural appropriation, class, migration and inequality—but the main preoccupation is dance. And dance, in the novel, is an expression of joy.

In Imbolo Mbue’s debut Behold the Dreamers, on the other hand, which chronicles a Cameroonian family’s experience of America, dance does not—as it were—take centre stage, but it is nontheless a powerful if understated motif. The novel describes Manhattan in the spring as a time when ‘people seemed on the verge of a song or a dance’: New Yorkers dance in Times Square after the election of Barack Obama; and Cameroonian immigrants celebrate the birth of their children by gathering together and dancing. Both books feature brief vignettes of children dancing precociously to music videos in front of the television, to the wild delight of their parents.

As evidenced by the Hollywood stars that Swing Time’s narrator reveres—Fred Astaire, the Nicholas Brothers, Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson, Jeni LeGon—dance is a practiced performance; you need years of training to make it look effortless and natural. In dance, there are many unspoken rules governing the way bodies move through the world.

As evidenced by the Hollywood stars that Swing Time’s narrator reveres—Fred Astaire, the Nicholas Brothers, Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson, Jeni LeGon—dance is a practiced performance; you need years of training to make it look effortless and natural. In dance, there are many unspoken rules governing the way bodies move through the world.

In Behold the Dreamers, the Jonga family participate in the global choreography of migrancy, moving from Limbe, Cameroon, a small town on the Atlantic Ocean, to New York City. In doing so, they are forced to learn a whole new set of steps. But despite the precarious nature of their new life in a foreign space, the Jongas appear to settle quickly into New York’s rhythm. After almost two years as a dishwasher and cab driver, Jende Jonga manages—through the help of a connected cousin—to land a well-paid job as a chauffeur for Clark Edwards, a high powered Lehman Brothers executive. His wife, Neni, arrives in the country in 2006, two years after her husband, and works as a home health aide for senior citizens while studying chemistry at a community college, with the intention of ultimately becoming a pharmacist. Neni loves New York as soon as she arrives, and after a year and a half considers it home:

For the first time in much too long, she didn’t wake up in the morning with no plans except to clean the house, go to the market, cook for her parents and siblings, take care of Liomi, meet with her friends and listen to them bash their mothers-in-law, go to bed and look forward to more of the same the next day because her life was going neither forward nor backward. And for the very first time in her life, she had a dream besides marriage and motherhood […]

Neni is in the country on a student visa, their son Liomi on a visitor visa, but Jende has a temporary work visa, and is waiting for the political asylum status he has applied for on murky evidence to be confirmed. The process of earning asylum tends to take so long that immigrants are able to live for decades in the country, and in Jende’s case it takes longer than usual. But the day after their daughter, Timba, is born, Jende receives a letter informing him that he is subject to removal from the United States, and will have to appear before an immigration judge to defend his case. His unscrupulous lawyer assures him they can appeal a negative decision, many times if necessary, to buy him time in the country. Shortly afterwards Jende loses his job, and is forced to take two dishwashing jobs, working six days a week for less than half his previous salary. He begins to suffer from debilitating back pain.

Neni is so desperate to stay in the United States that she blackmails Cindy Edwards—Clark’s wife—for $10 000 in an attempt to make their position more secure. But when Jende’s father dies and he is unable to travel to Limbe to fulfil his duty as the firstborn son, he finally decides he wants to go home. Neni frantically considers giving Liomi up for adoption, to a couple they know, so that at least he can become a US citizen. She suggests to Jende that they divorce so that she can marry a friend’s cousin and become a citizen that way. Having reached breaking point, Jende, in the midst of a bout of severe back pain, slaps her:

‘Don’t you make me hit you again,’ he growled as he pushed her hands away and clenched his fist. ‘I’m warning you.’

‘Oh, no, please hit me,’ she said. ‘Raise your hand and hit me again! America has beaten you and you don’t know what to do and now you think hitting me will make it better. Please, go ahead and hit—’

So he did. He hit her hard. One vicious slap on her cheek. Then another. And another. And a deafening one right over her ear. They landed on her face even before she was done asking for them. She squealed, stunned and pained; she fell on the ground wailing.

In these moments Jende and Neni are acting completely out of character. The battle for survival in the United States changes them, and exposes their inner cruelty.

Swing Time presents us with a character similar to Neni: Tracey, the narrator’s childhood friend. The setting is London, 1982, and as the only two ‘brown girls’ in a dance class, Tracey and the narrator are drawn together. But the narrator’s passion for dancing pales in comparison to Tracey’s natural brilliance:

I really felt that if I could dance like Tracey I would never want for anything else in this world. Other girls had rhythm in their limbs, some had it in their hips or their little backsides but she had rhythm in individual ligaments, probably in individual cells. Every movement was as sharp and precise as any child could hope to make it, her body could align itself with any time signature, no matter how intricate. Maybe you could say she was overly precise sometimes, not especially creative, or lacking in soul. But no one sane could quarrel with her technique. I was—I am—in awe of Tracey’s technique. She knew the right time to do everything.

The girls are close throughout their childhood, despite very different family circumstances, the narrator’s mother being determinedly upwardly mobile, while Tracey’s mother is firmly lodged in the housing estate. The pair start to grow apart during their teenage years, and Tracey’s childhood unruliness begins to develop into more troubling behaviour. ‘When Tracey’s time came there was no one to guide her over the threshold, to advise her or even tell her that this was a threshold she was crossing,’ Smith writes. One night, the narrator and her mother rescue a 15-year-old Tracey from a drug overdose, delivering her to the emergency room in the middle of the night. A while later, she is suspected of stealing the ticket takings from a children’s dance concert. Yet she excels at stage school, and ends up landing a role in a West End show. But the two lose touch completely and, years later, when the narrator happens across her again, Tracey’s life has not continued on that trajectory. Her theatre biography is oddly short, and she has three young children, all with different fathers. She becomes an obsessive anonymous online commenter, and also begins harassing the narrator’s mother, now a local political representative, via email, refusing to stop even when the elderly woman is dying in a hospice.

Dancing on stage is one thing. All it takes is initial skill and hours of disciplined practice. But the possibilities for moving through the world as a success become precarious without something far more rare and unobtainable: luck.

In Swing Time, it is the narrator who is described almost exclusively as lucky. She considers herself lucky that she was not sexually abused as a child, as many of her women friends were—including, she surmises, Tracey. She is lucky that one of her teachers shares her love for Tin Pan Alley-era music, and encourages her interest. She is lucky to bag a job at a hip television show in her early twenties, where despite having no career direction she progresses quickly. She is lucky that, after a one-night stand, the results of an Aids test are negative. She is lucky to have had a father who loved her, as her mother points out when she tells her about Tracey’s increasingly abusive emails:

I felt her fingers pinching me, bony in their grip.

‘You were lucky, you had this wonderful father. She didn’t have that. You don’t know how that feels because you’re lucky, really you were born lucky—but I know.’

Similarly, in Behold the Dreamers, luck is what governs success or failure. When Jende informs his lawyer, Bubakar, that he has decided to opt for voluntary departure instead of fighting his case, Bubakar says: ‘America can be hell, I know. Man nova see suffer until the day ei enter America, make I tell you.’ But he adds that success is within everyone’s reach: ‘I am an example that with hard work and perseverance, anyone can do it.’ Jende discusses the conversation with his cousin Winston, the Wall Street lawyer, who calls Bubakar’s opinion ‘rubbish’, and points out that even if Jende did manage to get his papers, as a black African immigrant male without an education he would probably never be able to make enough money to support his family. However, even Winston seems reluctant to accept the part luck has played in his own success.

‘It’s people like you who are lucky,’ Jende said. ‘To have a good job and money.’

‘You think I’m lucky?’

‘Are you not luckier than the rest of us? If you don’t think you’re lucky, you can come live in this Harlem dumpster and I’ll live near Columbus Circle.’

‘I guess I’m lucky,’ Winston said after a chuckle. ‘I work like a donkey from morning to night for the people who are taking everything and leaving only a little for everyone else. But at the end of the day, I go home with pile of their dirty money, so—’

‘But how man go do?’

‘How man go do? I cannot do anything. And even if I could I probably wouldn’t, because I like the money, even if I hate how I make it.’

‘As the Americans would say, “Gotta do wha ya gotta do.”’

Behold the Dreamers convinces us that a return to Cameroon will be best for Jende—whose chronic stress-induced backache clears up on its own after his decision to do so—and the children, who will grow up surrounded by family in a comfortable environment, attending the best schools and retaining a connection with their culture. But it never resolves or attempts to resolve the fact that Neni will have her hope of a successful and fulfilling career dashed. With the blackmail money and the dollars they’ve saved, Jende tells her, ‘You will live like a queen.’ But Neni was in America legally—unlike Jende—and she was working towards a very fulfilling dream, again unlike Jende, who had no real career aspirations. Neni was also arguably working harder, as she had to take care of the children and the housework, work an unpleasant job, and then make time to study, often in the early hours of the morning. Jende may have believed there was more pressure on him, as a man and and the ‘head of the household’, but there was far more weight on Neni’s shoulders—a burden made all the heavier by a lack of power in her partnership with Jende, and a lack of social power as a black foreigner generally.

In leaving America, Neni has far more to lose. She is destined to become Cindy Clark’s Cameroonian carbon copy: a rich, lonely woman in a big, empty house. The night before the family are set to leave, Neni sits alone in the apartment, on the floor: ‘It seemed smaller and darker. It felt strange, like being in a faraway cave in a forest in a country she’d never been to. It felt as if she was in a dream about a home that had never been hers.’

The subtlety in this novel’s treatment of the American Dream is in its many strands and characters. What seems to have captured the public imagination, however, is Mbue’s own ‘rags-to-riches’ tale. The oft-repeated story centres on how she grew up—like her characters, in Limbe—in a house with no running water or electricity; came to America to study on the generosity of family; lost her job during the recession; and was out of work for some time before being given a million-dollar advance for her debut novel. Interviewers bring these facts up with barely disguised glee, as if delighted to point out that Mbue’s own experience disproves her fiction.

2.

Similar real-world circumstances pierce the fictional world of Swing Time, being the first novel Smith has written in the first person. In recent interviews, she has described viewing first person narration prior to writing the book as a ‘limitation’ and as too ‘inward facing’. She has also mentioned a desire to avoid igniting the ‘autobiographical instinct’ that compels readers to conflate author and narrator, and condemns authors to face irrelevant and boring personal questions for years afterwards in interviews.

As early as the Prologue, the narrator of Swing Time describes herself as ‘a kind of shadow’: ‘I had always tried to attach myself to the light of other people,’ she says. ‘I had never had any light of my own.’ She is almost a cypher, and is never named. Another subtle lacuna in the novel is the name of the African country the narrator travels to and which is the setting for a significant portion of the narrative. We are given quite a lot of information about the country: we know that it is in West Africa, and we are provided with the name of the capital city and a nearby town. However, these clues proved to be too obscure for a number of readers and even reviewers, who mistakenly assume the country is Ghana, and do not bother to reach for their phones to check. Smith has described this disinterest as ‘mind boggling’.

A clue, perhaps, to why Smith leaves these gaps appears in her essay ‘Rereading Barthes and Nabokov’, from her 2009 non-fiction collection Changing My Mind. In it, Smith mentions Roland Barthes’ ‘rather wonderful’ distinction between ‘readerly’ and ‘writerly’ texts, the former asking ‘little or nothing of their readers’, the latter ‘demanding a great effort from its reader, a creative engagement’. ‘In a writerly text,’ she writes, ‘the reader, through reading, is actually reconstructing the act of writing.’ In the essay Smith also describes being pulled, throughout her reading life, between Barthes’ insistence that the author is dead and the text free and Vladimir Nabokov’s insistence on the primacy of the author. She concludes that she has come to believe that the ‘free flow of literary meaning’ is not as essential to the reading experience as she once believed it was: ‘I’ve changed my mind,’ she writes:

The assumption that what a reader wants most is unfettered freedom, rather than limited, directed, play, or that one should automatically feel nostalgia for a bygone age of collective, anonymous authorship—none of this feels at all obvious to me anymore. The house rules of a novel, the laying down of the author’s peculiar terms—all of this is what interests me. This is where my pleasure is. […] Nowadays I know the true reason I read is to feel less alone, to make a connection with a consciousness other than my own. To this end I find myself placing a cautious faith in the difficult partnership between reader and writer, that discrete struggle to reveal an individual’s experience of the world through the unstable medium of language. Not a refusal of meaning, then, but a quest for it.

And so we discover that in Swing Time Smith is not only challenging us to create part of the story ourselves, but is also attempting to ‘make a connection’ with the reader, to make us realise that our vague, fuzzy impression of what The Gambia is in the book is echoed in real-world global power dynamics. Judging by the number of autobiographical questions she has been asked in interviews since Swing Time’s publication, and the number of times The Gambia has been misidentified, Smith is right to have no more than a ‘cautious’ faith in her partnership with her readers.

Jende and Neni suffer in pursuit of happiness, and their characters are damaged as a result. But there is an intricacy and an ambiguity in Behold the Dreamers, too, which demands a touch of Barthesian ‘creative engagement’. During the Jongas’ farewell party, Ivorian singer Meiway’s famous hit ‘200% Zoblazo’ comes on the sound system. Soon, everyone is on the dance floor, even Neni, whose ‘hips couldn’t help swaying to music this good’:

They jumped and skipped as they pumped their fists, singing together as loud as they could, Blazo, blazo, zoblazo, on a gagné! On a gagné! When one of Jende’s non-African friends from work asked him what the song meant, he shouted, without pausing to catch his breath, it means we have won, man. It means we have won!

Index

Books

- Changing my Mind by Zadie Smith

Essays

- ‘Rereading Barthes and Nabokov’ by Zadie Smith, collected in Changing My Mind

Music

- ‘200% Zoblazo’ by Frederic Desire Ehui / Meiway