The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec sat down with Margie Orford to talk about the challenges of writing about sexual violence, the politics of shame, and her new novel The Eye of the Beholder.

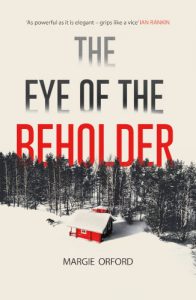

The Eye of the Beholder

Margie Orford

Canongate, 2022

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: I’d like to say, before we begin, congratulations on your recent nuptials—

Margie Orford: Ha! My gratuitous wedding.

The JRB: But also my condolences for the sudden loss of your sister. It’s been quite a tumultuous couple of months for you. But how are you enjoying being back in South Africa?

Margie Orford: Oh, it’s so nice to be back. Covid interrupted my being here and being there, and it just so nice to get back and see that everyone seems so happy that there’s another book out. And actually Jonathan Ball are republishing the Clare Hart books with beautiful new jackets and shouts, so that’s been great. And Open Book is always fantastic.

The JRB: Catching up with everyone.

Margie Orford: Yeah, catching up with everyone, and here in South Africa, one’s writing, literature is meaningful to people. It might not translate into huge book sales necessarily but it means a lot to people, the conversations that a book can open up, and that’s always fantastic.

The JRB: I’ve never been to a book festival overseas, but I get the impression that the questions you get in South Africa are quite different to the ones you get over there.

Margie Orford: Very different. I’ve just been at the Edinburgh Festival, and I find how it’s curated around intellectual questions and questions of social and political meaning, that’s a fantastic festival. Scotland, with its engagement with postcolonialism and independence, I love going to that one. But the questions are very different. Here, it’s like books have a real meaning to people. There are such pressing issues, such political issues, and even if it’s fiction, people don’t reduce it down to a story of yourself necessarily, but storytelling and the fashioning of the world is of great importance here. I mean I’ve been interviewed by some great people, but it’s much more literature as entertainment. Do you know what I mean? But the festival here brings it right up close, how it really means something in people’s lives. People can think through things politically through a book, which is fantastic. And it’s a creative politics, you know, I don’t find it reductionist. And this is a country where books were banned until nineteen-ninety. I’ve worked with Russian writers, writers from the Eastern Bloc, and if books have been threatened and taken away from people it takes a long time to lose that memory that these things have power.

The JRB: I think people in South Africa are reading for slightly different reasons, almost. I don’t want to claim South African exceptionalism, we’re not special, but—

Margie Orford: You’re quite special.

The JRB: We seem to connect literature and creative writing with our social and political reality.

Margie Orford: That’s true. I do as well. And sometimes I think where it’s tricky for me in an English setting is, I take my work seriously, and other people’s work seriously. I’ve kind of used and abused genre, but with the intention, it seemed to me the best way to get under the skin of this society. Actually when I get back I’m going to teach a master’s class at Norwich about writing about violence and especially writing violence against women, and I take it seriously. I think even if you’re writing entertaining books you’ve got an ethical responsibility about what you do.

The JRB: Let’s get down to this book. This is your first standalone (or not? I’ll ask you about that later) and it comes after a break of nine years. So why did you decide to write something different? How did it feel to return to fiction? Did you miss Clare, writing this book?

Margie Orford: I do miss Clare, she sort of nags me now and again, I have to say. I had drafted and written a Clare Hart novel, a sixth one, which had been titled Teacher’s Pet. I think two things happened. One, I was absolutely burnt out from writing those books. I wrote them back-to-back, one after the other. And basically for seven years I didn’t have even a weekend off because I did all the Clare books and I did lots of other books and I was completely burnt out, if I look back on it now.

The JRB: You were prolific. The publication schedule was very regular.

Margie Orford: Ja. It was relentless. And the material, what I was trying to write about South Africa, was harrowing. And at the time I’d used that sort of journalist sensibility, which is just like, put on the emotional equivalent of a flak jacket and keep going. I think I exhausted myself. Then in 2015, as part of the gap, I had these three residencies, one was at York, one in Scotland and one in Italy. And I suppose it gave me a bit of a rest. And then I had a fellowship at Oxford, and there was a kind of a drift. But I’d written the Clare Hart which was an investigation of the production of child pornography and pornography in general in Cape Town, which I had come across in research that I’d been doing with the police and various organisations that I worked with, and I found that with the investigative genre, Clare with her investigative eye, I was just reproducing the same gaze, this male gaze that both desires and demands and then creates one of the most invisible and pernicious forms of crime, especially against young children, or women who are vulnerable. So I just scrapped that book and I cancelled my book deals and said I can’t do this, it’s unethical. But I still wanted to do this book because I’d been through the five Clare Hart novels which are a kind of portrait of organised misogyny, and for me what I was writing about in The Eye of the Beholder, this gaze, the thing that turns women into an object, it caught me that—What is it if you are a thing, what does it mean? It’s a cliche that we just brush over because we’re so used to it, but I stayed with it. What happens when the way someone looks at you and the power that that gaze brings with it turns you into a thing? This battle of how to be human, which is an old one, Aristotle doesn’t think women had souls, there are lots of religious phases that have said we’re not fully human. So I wanted to write a book about images and the creation of images in which you never see the images. You don’t discover them, all I was trying to give was what it feels like for the person.

The other thing that informed this book, many years ago, I did investigative piece in the early 2000s and I investigated a man who had set himself up as a photographer, and then he advertised for young models, and then he duped or drugged the five young women who I interviewed. It was long before revenge porn had started, it was really the beginning of this stuff. Anyway, we did the piece and it was heartbreaking. A couple of the girls were addicts, the others were coerced, and I saw some of this footage, it was terrible. And this one girl said to me, it’s never finished, what he did to me is never over, I can be asleep and that crime will be happening again.

The JRB: Because of the psychological aspect of it and because of the digital aspect?

Margie Orford: Literally, they’re going online and each time it is a crime scene, again. So my other question was—What happens when you have a crime or a sin committed against a person that never ever comes to an end? Because the fantasy of therapy or police sentencing is that then it’s over and it’s all tied it up, and we know it doesn’t work. So that idea of a crime that never ends, I found that fascinating because how do you escape from that gaze? It holds you forever. And it chimed with what I know about the abuse of children and sexual trauma, it stays with people, it resurfaces. That didn’t work with a procedural. I needed to go into the psyche of these three protagonists, these three women, Cora Berger, who’s about fifty, I guess, and her daughter Freya, who’s living with a mother who has a trauma she’s dissociated from, and then Angel Lamar, who’s not her actual daughter but in a way is her daughter in terms of the shared experience they have. And they just go off with different reactions, Cora has turned hers inwards into shame and a kind of splitting off and a form of creativity, it fuels her, she’s a painter. Whereas Angel turns it into sheer rage, she turns her fury out onto the world rather than in onto herself.

The JRB: I loved Angel. But that ethics of representing violence against women or children that you grappled with in the writing is then mirrored in the book in Cora’s art. She paints a series of self-portraits of herself as a pubescent child, ‘her child’s body budding with womanhood and the way men had started to look at her’, but then comes to see them as ‘miniature obscenities that drew the viewer so close that they made all complicit’. Did you see your own inner dialogue echoed in Cora’s?

Margie Orford: Yes, very much so. First, Cora is not me. But we are very closely related, let me put it like that. So, one of the ideas of feminism, of equality, is the guys do this, the girls can do this, that sort of ladder in feminism which has never been mine. I am much more interested in the thinking that comes from Luce Irigaray and Monique Wittig, the sort of French feminist idea of difference, and that if you produce a spectacle of violence, for instance, or obscenity, it will function in the world, it doesn’t matter whether you’re a man or woman who does it, it will be out there in the world and will affect people in the same sort of way. But it’s a complicated thing, because on the other side, one of the questions that I always had through the Clare Hart novels was, if I don’t write down what I’ve witnessed, who will? We can easily say we can’t look at this stuff, we can’t record it because it’s too shocking, but then what happens is there’s this silence, there’s this lacuna around it and it disappears.

The JRB: So you almost have a responsibility.

Margie Orford: Yes, to bear witness to the pain of others, as Susan Sontag put it. That book of Sontag’s called Regarding the Pain of Others is something that has framed me and I think there is no easy moral ground. There is no place where you can say, oh this is the simple solution. We’ll hide everything, we’ll show everything. So in Cora’s work she’s doing two things. She’s South African originally and she’s trying to work through that intimate political fracture, the intimacy of racial politics that we all are initiated into and made part of, and the shame of sexuality, and she does it through representation. And there’s this big furore because she does these things about herself as a young woman, and there’s all this drama and saga attached to her daughter Freya, and ‘she’s harmed her daughter’. So it’s part of this current debate, like where can you rest? What do you do? What risks can you take and not take? And there have been some very interesting parallels, the example I think of is Sally Mann, an American photographer who did an incredible body of work around her children and her family, and they’re all these naked pictures of the kids, somewhere lush and Southern with lots of trees, but these gorgeous little children, always naked, as they grow up and into adolescence, and then suddenly there was this furore that this was somehow pornographic. And that’s where I think The Eye of the Beholder, which is the title of the book, is so important in how one receives the look, how one receives the gaze, because if you just look at naked kids as gorgeous little feral free creatures it’s harmless, if you look at them in another way, it’s not. So the location of the sin is not with the person who’s looked at, it very often is the person who looks, who then objectifies. There isn’t an easy resting place, as Cora finds out.

The JRB: The artist I had in the back of my mind was Marlene Dumas.

Margie Orford: Oh, yes. She’s been such an influence.

The JRB: A South African who’s ‘made it big’ in Europe. In an interview you gave a few years ago (to Africa in Words) you mentioned a quotation from Dumas about how ‘painters avoid completely representations of sex and death, whereas in literature people do write about it more’, and she asked whether writers make things worse or collude when writing about certain subjects. Was Dumas an inspiration for the character of Cora?

Margie Orford: Of course she paints so much about pornography, and she has a whole series of paintings of a woman PLO fighter who was shot in the head, and pictures of her body. Marlene Dumas has really been an influence on me, how she creates scenes, the positioning of her gaze when she creates, because I think very visually when I’m writing. There’s such an emotional valence about whether you’re far or near or right up close.

The JRB: I think the gaze that comes from her work is so powerful.

Margie Orford: So, so, so powerful. There’s a whole series she did from porn paintings, and she manages, with her sheer genius of empathy, I suppose, or observation, to capture … what always struck me about those paintings is how these women who were posing, and the girls, were both there and absent. So something I can explore in writing is how people disassociate, and Cora does. And the compulsive part of her painting, which maybe is the compulsive part of my writing, is that you return to the repressed, that’s Freud’s idea of trauma, the return of the repressed, but you also return to it to try and resolve it, try and resolve it, try and resolve it.

The JRB: Which is what Cora does with Yves I suppose.

Margie Orford: Ja. Ooh, he’s so horrible.

The JRB: After the exhibition in which Cora shows her self-portraits there’s a media uproar and public backlash, I guess you could say she’s almost ‘cancelled’, not quite cancelled as she does continue working. As someone passionate about freedom of speech, I wanted to ask how you would have felt about this if you existed in the world of the novel.

Margie Orford: I did think about it a lot. These portraits that she does are these tiny little peepshow-sized postcards, they were produced a lot in the early nineteen-hundreds, the series is called ‘Forbidden Fruit’ and you go right up to them and get a shock, and it reproduces that transgression. So the mob of disapproval is led by the Daily Mail and these ghastly British tabloids—I was thinking of the polarity and stupidity of what are called the culture wars, everyone rushes over to this extreme and then over to the other extreme. And what Cora is trying to do is resolve something that many people suffer from, would only benefit from trying to get to some kind of understanding of, and that the middle ground and the places of healing and comprehension are complicated and nuanced. And you need time and slowness and proximity. The ease with which people are stoked up, often by the Tory right or people like Trump, you create enemies out of knowledge and understanding. But of course her work is counterbalanced by the ubiquity of pornography, because there isn’t a furore about that. I’ve changed my views twice on pornography. I used to be very much of the school of Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin that it’s like an assault, then I thought, no, no, you’re too prudish and you were brought up in a very puritanical country. But what I’ve seen with pornography and the way the vulnerable, which is ninety per cent women or children, and a few boys, is absolutely reductive and dangerous. And you see more and more these cases of strangling and choking and the sort of violence women are meant to enjoy and I think it’s harmful. So I’ve come around. And yet there’s no reaction about that.

The JRB: What I struggle with is the idea of coerced consent. When there’s a power imbalance.

Margie Orford: Yes, and again it’s a thing that requires complexity, people’s sexualities are very complex. There can be great desire in submission. It’s the image making and then the reduction of a full human response to this two-dimensional thing. I don’t have a solution. But I think it’s something we should interrogate. Well, I’m certainly interrogating it.

The JRB: In a very fascinating way. You get into the mind of Gen Z in this book, you’ve got two wonderful, complex younger women characters, Freya and Angel. Angel I found fascinating, even though she has less of an inner life than your other characters. Was that a conscious decision, to pare her inner monologue down, until later in the novel?

Margie Orford: Yes, I did that intentionally. So Angel is about eighteen or nineteen and Freya is the same age. They’re like the light and the dark daughters. Freya is Cora’s own daughter and has grown up protected and in a safe world, alongside the internalised trauma of her mother. I’m interested in that second generation, in our mothers, people who didn’t say anything and the idea of holding in and putting it aside. I thought very carefully about Angel and how we see her and how we know her. She’s very potent to me, she’s got great energy. I thought of Diana the Huntress and Tank Girl. But mainly what I thought of is what happens to a loving little girl whose life is radically interrupted by the death of her mother. And I gave her Nabokov’s Lolita’s backstory, her mother’s killed in a car accident and her stepfather steps in. And one of the effects I’ve seen with trauma, especially traumatic childhood stuff, is that it does interrupt and break one’s relationship with oneself. So you can go into Freya’s mind because she has a complicated life and an overprotective mother and maybe she needs to separate more, etcetera, but she’s a more regular kid. All Angel can do is act in the world in what one would call a masculine way, but which I think is a response of where the capacity for feeling has been destroyed in her. It comes out in her ability to connect with animals and also with little children, where there’s a non-threatening gaze at her, something that’s just accepting. But you get her in her moments of lull or quiet or on an aeroplane, and there are these overwhelming thoughts, like—What happened with her mother, did her mother abandon her, did her mother collude? And I was thinking a lot about what it’s like to live in a patriarchy in which we are all unmothered, the maternal is repressed, if we associate the maternal with care and growth and generative, which is what I do. So they were this yin and yang for me, these young women. Freya is also not unscathed. Negative weak father, and this mother who disappears. Physically or she disappears into herself. So what is it like to love someone who’s damaged but doesn’t know they’re damaged?

The JRB: I think what saves that relationship between Freya and Cora is that intense bond and love, and they’re fairly confident in that, both of them.

Margie Orford: Ja, no, they love each other. And Cora was interesting to me because her love for her daughter is not at all idealised or idealistic. She intently knows and loves that specific person who is Freya. And yet she carries on being herself.

The JRB: It may have ended up being cheesy, but I found myself hoping Dawid, Cora’s childhood friend on the farm in the Free State, the son of her nanny, who she was forced to let go of by her father, would return at some point. Did you ever consider that as a plot point?

Margie Orford: Dawid was so present to me all the time. There was a whole number of things going on there and realistically, in a South African economy of relations, he would never reappear.

The JRB: Exactly.

Margie Orford: And that was the tragedy. There was a big rash, I would call them, of memoirs and novels and books that came out in the nineties and early two-thousands by white writers who wrote about these idyllic childhoods on farms in particular and they would be friendly and then, whoa, they would discover apartheid and, bang, that would be the end of the book. I always had a political and creative issue with that because that’s the point, to me, where you start. So in that very complex moment with Dawid, which I borrowed—I wrote a piece in Granta which was published in an edition a couple of years ago, under ‘The Politics of Feeling’. When I was young, we visited a farm near Bloemfontein and I witnessed this boy being beaten by the farmer and it absolutely stayed with me. And of course, I’m perfectly well aware that to be beaten is ten million times worse, but it was that witnessing and then telling people that this had happened, and nothing was done. Everyone said to me, oh, he must have done something or, oh, you couldn’t have seen it. And in that moment, I felt this terrible shame of seeing something and not being able to do anything about it, which is that sort of impotence which Cora has. So in a way it was an experience I borrowed from myself because it was the moment in which suddenly the whole social structure of power and dominance and maleness revealed itself, because that is a scene of prominent masculinity asserting itself in the face of everything. So Dawid couldn’t come back. Where would he have gone? The falsity of those intense relationships, when in fact that boy would have gone with his mum back to a house without electricity. It’s that fall out of a completely false sense of paradise. But I used that incident to mark the moment in which the fracture starts in Cora, this feeling of shame and responsibility, and also an inurement to violence which I think made her susceptible in her later life to somebody like Yves. I do wonder what happens in the psyche that makes people not think, holy fuck, but that was wrong what you just did, and then leave. Something has conditioned them into having a feeling of, it feels like home, and if home contained this unquestioning violence or erasure how you act is distorted and peculiar, and that feeling of culpability and helplessness in a child plays out in complex ways in adulthood, where you become less helpless, you can do things but you’ve got all these breaks in yourself.

The JRB: So calling the farm Eden was kind of perfect. Loaded with meaning.

Margie Orford: I know, I think about how many farms there are today still called ‘Paradys’. But, you know, you’ve got to allow fiction writers a bit of heavy handedness.

The JRB: While I was reading I was very pleased that I wasn’t seeing the film of this book in my head, because I feel a lot of crime and thrillers are writing with the series or the film in mind and it’s starting to really get on my nerves.

Margie Orford: It’s interesting, it’s absolutely hopeless for cinema, because it’s interior and it’s memory, which doesn’t work in cinema. I think it’s a very visual book. But you can’t unfold TV series backwards unless you have corny flashbacks all the time, which is incredibly boring. In fiction you have the mind, the interiority of the person, and the action happening at the same time. But I agree with you, they’re such different forms. I’ve been working on a TV thing with the Clare Hart stuff endlessly and it’s different. It’s interesting. My work is very visual but it’s difficult to translate because it’s so much about why people do things, which is often rooted in long before the present moment.

The JRB: It was refreshing to read a new novel that makes no mention of the recent pandemic, it made me think that maybe it really is over. Was that a conscious decision on your part?

Margie Orford: Well, I wrote it before the pandemic. Part of the reason for the long gap is that I cancelled the last Clare Hart, and then I felt so chained to this production line and then I couldn’t sell the book. I was obsessed with writing the book, I just thought I have to write about this unbelievably difficult thing. Part of myself that’s in there is, you might have had this experience, so many women I know have had it, you’re running around just being your little girl child self and then somebody looks at you, just around the time of your first period, and it’s can often be someone you actually know, but they’re noticing you as a sexual being, and in that gaze you suddenly are yourself but you’re seeing yourself from this other gaze, and into each cell goes this little VHS of shame which plays for the rest of your life. Suddenly you realise people will predate on you somehow, they see you in a way in which you never imagine yourself. It was really that split, I think, which is certainly my experience of being female in a culture of a particular gaze. I don’t want to draw analogies to being queer or to being a person of colour, but where you are not the norm and you are a thing to be looked at. It’s a really strange rupture in the psyche and often it comes with violence and aggression. Then Me Too happened and, bang, this book just sold.

The JRB: Oh, really?

Margie Orford: So obviously I redrafted it and I found it a bit slow and I found it difficult, it was hard to write. Challenging. Because of the complexity of the material. And a lot of stuff got stripped away, there was more complex, procedural stuff and I just thought—No, chuck all of that stuff out. So that’s part of the long interruption. So the pandemic was not there. But, you so kindly mentioned my sister earlier, I had just started the copy edit when I got the call to come back to Namibia because she had this aneurysm, I got there and she was in a coma and we had to, you know, decide to put the life support off. There’s an intense feeling of isolation in that book. These characters are so isolated and so remote and cut off. So the main editing was done in the pandemic, and then me being in this intense, heightened state of isolation and grief, which came after, because my sister and I were like one person, we used to talk every day. So the pandemic is not there. The novel was drafted before, and then published after the pandemic. But I do think some of the loneliness, I mean, a number of interviewers have asked me about how isolated they all are. They are very unable to link up to the world, all three of those characters.

The JRB: Well, I’m very surprised you had trouble selling a novel.

Margie Orford: Me as well! Because editors loved it and then the marketing people were like, what is it? Is it literary? It’s not crime, it’s so extreme. And then it just sold, fantastic Ellah Wakatama.

The JRB: Right, I saw you thanked her in the Acknowledgments for ‘believing in the book from the beginning’.

Margie Orford: Ja, she knows my work and she bought it for Canongate. And then Jonathan Ball obviously took it up.

The JRB: That sense of isolation comes through in the setting as well. It’s a very frosty, icy book, which is quite unusual for you, obviously something you’ve been experiencing more recently, but you were formed in the heat.

Margie Orford: Yes, I was formed in the heat and formed by the heat, but I was also formed by very remote landscapes, growing up in Namibia, and the size and splendour of a huge landscape like the Namib, for instance. So when Cora escapes right at the beginning from that little skiing hut, I have spent some time in snow and ice, and for a southern African it’s utterly disorientating. Nothing you know helps you in this landscape you’re in, and it’s a lethal one.

The JRB: I found it truly bizarre, when I was in Switzerland, to be in a country where if you stayed outside for more than sort of twenty minutes, you could die.

Margie Orford: Yes, no, me too! We just have no idea how to be in this landscape.

The JRB: If you take your hand out of your glove, it could fall off.

Margie Orford: Yes! So I put Cora in a landscape where she absolutely has lost her bearings, psychologically, morally, emotionally, in all sorts of ways, and then she’s in this lethal storm. The other reason why I wanted to put her in that part of Canada was, you write about South Africa and you are looking at the familiar until it becomes strange, as a writer. For me, writing about other landscapes, it’s completely strange until I look at it long enough to find some familiarity. There’s a kind of reverse. But I did want to, and it’s acknowledged in the book, write about this massacre in Montreal, in 1989, of all these women students, which was the first explicitly misogynist massacre, mass murder, of women by a man because they were out in public. That case has stayed with me. And we’re seeing this more and more with these ‘incels’. It was when I realised—Okay, the misogyny and sexism is a political structure. We experience it intimately and as if it’s part of our breathing, but it’s a public politics that we internalise.

The JRB: Before you go, since writers tend to be readers, we like to ask writers what they’re reading. What have you been reading recently that you would recommend?

Margie Orford: Well, not new books, but Tim Winton’s memoir, it’s called Island Home: A Landscape Memoir, is just incredible. I’m reading Pumla Dineo Gqola’s Female Fear Factory and The Quality of Mercy by Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu, which I just picked up here in Cape Town.

The JRB: You should try to get Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu’s first two. She’s one of my favourites.

Margie Orford: I just have these space limits! But we were on a panel together and she’s such an interesting person. And then I’m totally late to the party but there’s an American writer called Elizabeth Strout who wrote Olive Kitteridge and then Oh, William! and just blew me away, her economy of emotion, and I just thought—Life goals, life goals.

The JRB: Olive Kitteridge is one of the best woman characters I think I’ve read.

Margie Orford: Oh, she’s just incredible, and I felt such an emotional landscape rapport. With Cora I tried so hard to create a character in which I didn’t judge her, she just did her life. And women edit themselves out, you know. And when I read Olive Kitteridge I thought, okay, we’re going to do it this way. Murderous and hopeless and hilarious at the same time. I’ve actually been reading a lot of nonfiction about women and violence and coercive control, plus I read the newspapers where the stories about women seem fictional and weird. Because I do want to bring Angel back.

The JRB: That’s just what I was going to say: and finally, will we be seeing Angel again? I hope so.

Margie Orford: I think you will see Angel. I mean, her plan is to kill every man who ever looked at her on the internet so she’s got millions of people, a sort of manicide, which I don’t think is possible. But I want to follow her and what I only realised at the end of this book is that I tried to bring her into Cora’s fold as like a daughter, you know, sort of adopted. But it didn’t work, she’s too angry still. But as Cora was defined all her life by these experiences of abuse as a young girl, so is Angel, but they’re both completely tied to these men who did evil to them. And I was thinking—How do I free her from being this vengeance principle? Because it’s kind of satisfying to take down the baddies, but all her creativity, her intelligence, her capacity for love, her generative ability is channelled into this unbearable anxiety, which she deals with by hunting men. She’s as much a slave and somebody who turns it inward. So my serious question in the next book is how do I liberate her from that? Is it possible? I don’t know. I really don’t know. I need to figure that out.

The JRB: You’ll have to read up on the philosophy of revenge or something.

Margie Orford: Maybe I just have a few more people I want to kill off, and then when I’m done with my list then Angel will be free. Oh, and I’ve been working on a memoir as well.

The JRB: I saw you mention that.

Margie Orford: I haven’t been able to go back to it since my sister died. And I don’t… I’m going to try, but I don’t know if it’s time. It’s not just writerly … literally my heart starts pounding when I go to it. So I have to see. Otherwise, I think Angel’s lurking around. I wanted to do something with her and those British Metropolitan Police and how racist and unbelievably sexist … there’s something going on. I want to write about cops, I think, or the wives of cops, I don’t know. We’ll see.

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor. Follow her on Twitter.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.