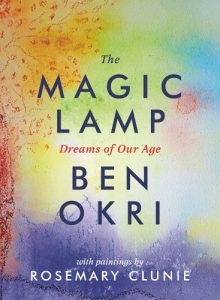

Wamuwi Mbao reviews The Magic Lamp, a new collection of meditations and stories by Ben Okri, illustrated by Rosemary Clunie.

The Magic Lamp: Dreams of Our Age

Ben Okri, illustrated by Rosemary Clunie

Head of Zeus, 2017

What is the use of stories in an age of malaise? In The Magic Lamp, Ben Okri suggests that they are not simply necessary, but urgently so. Stories encourage us to think through our predicament, to question our hubris and to uncouple ourselves from the entrapment of false imperatives. Written over five years, this slim collection is almost a primer for reading the world in a more expansive way.

Okri is a writer to whom the term ‘magical realism’ is often lazily appended (ditto ‘Booker Prize winner’). The literature that clusters under this broad umbrella can often sound rather pleased with itself for being so awfully, sprawlingly clever. Many people are daunted by the idea of tackling a traditional magical realist novel, which may feature forty diffuse characters with implausible names and strange habits, relying greatly on detail for its vivid ingenuity.

The Magic Lamp avoids this kind of genre entrapment because it is more receptive to allowing detail to suggest itself. Okri is venturing into an area where meaning occurs, rather than being conjured into being. Were I pushed to find a term for it, I might call it ‘ambient literature’. The book is a collaborative dream theatre in which twenty-five stories interact with twenty-five paintings, by the artist Rosemary Clunie, and the result is a beautiful, multicoloured adult’s storybook: a defence of magic as the vital energy behind life, an energy that cannot be summoned at will, but which instead appears in introspection. Like much of Okri’s back catalogue, The Magic Lamp concerns itself with creative possibility in the midst of change, especially when that change disrupts the seemingly well-ordered universe we inhabit, revealing the chaos behind the curtain.

Composed of drifting, ethereal wanderings, The Magic Lamp is occasioned by a sense that we are teetering between our private calamities and those of the times in which we find ourselves. Characters become estranged from their values. Others are trapped by the awareness of what they do not know, lurking beyond the threshold. The stories locate their politics in the realm of feeling: some characters express longings for worlds that have vanished, but a different set of characters in a different story are just as likely to remake a world that seems on the brink of annihilation.

The stories have a hallucinogenic quality about them, an acid-trip fantasy where the boundaries between the waking world and the land of dreams seems to melt away. And yet the collection manages the trick of being both abstract and concise. None of the segments lasts past five pages. Several are over in barely three turns. They tell eccentric, incantatory stories that unspool over pages daubed in Clunie’s waxy artworks.

These contemplatively lush, colour-washed paintings submit themselves to Okri’s improvisational writing, and they lend the book a conceptual intrigue that is refreshing. The art—in which juggernaut heads and squiggly figures (at a squint, some of them look like someone has coloured in a Quentin Blake illustration)—is not arranged alongside the text: this is not a coffee table book. Rather, they sit hospitably on the page, sometimes separating one story from the next, and so interrupting the and-then-what flow normal reading instils. They are both strange and known, and they defy easy interpreting, which makes them ideal companion pieces for stories that are variously about what dreams do for us, what dreams enable us to feel, and what we might learn from them.

In Okri’s writing, dreams often figure as the antidote to a ramshackle world. In The Magic Lamp, the temptation is to look for clues to the overall project in the makeup of the text and its background imagery. While some of the stories infer political or ecological criticism, most of the text is too abstract to sustain such an interpretation. The two art forms maintain an agreeably organic spaciousness, where paths backtrack, ideas reverse, and darkness and disillusionment may descend or lift suddenly. Okri’s moodscapes here have a folkloric timbre, but they ultimately have more in common with Brian Eno or Sufjan Stevens than they do with any traditional form of narrative. One character, observing his father’s dotage, remarks that ‘the stick on which he leaned writhed with stories’. The word and the image coalesce most agreeably.

If Okri’s writing ever falters slightly, it is because it cannot always sustain the daytripping eclecticism over the course of so many tales. Overburdened by all this ambience, he tends to fall back on easy inversions. Some of these are lovely:

The way we saw the world determined how the world revealed itself to us. The world had all along mirrored our seeing.

This is a lucid way to express the limits of language. But then, a little later, we have the idea occurring once more, less successfully:

We acquired more knowledge of the world and less knowledge of ourselves. We knew more, but somehow we knew less.

Too many of these in short succession start to feel silly, explaining the magic rather than relaying the experience of it. And note the false modesty of that ‘somehow’, more rhetorical add-on than actual doubt. The repetitiousness weakens the reader’s inclination to follow the narrative. At moments like these, one feels the lag of interpretation making its presence felt.

But then, this is a storybook, and storybooks are not meant to be read in one sitting. The book rewards measured, attentive reading in much the same way that looking at a painting draws out subtle nuances of meaning previously unglimpsed. Okri’s writing, especially in stories like ‘Return to the City of Dreams’, is engaging, drawing the reader in and encouraging us to linger over the words. Read the story again and you notice how Okri has taken the conventional narrative structure and used it to show precisely how meaning always overflows the edges of the dreaming world.

The Magic Lamp is idiosyncratic and uneven, but deeply affecting in its call for us to remember what is most salient in dreaming. They are exercises in dealing with unsettlement, in finding the will to reconstruct ourselves in new and liberated ways. For a writer of Okri’s standing, The Magic Lamp is a minor work, but its slightness is its strength.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.