David van Schoor responds to Sarah Ruden’s letter, published in our December issue, addressing Van Schoor’s review of her translation of Augustine’s Confessions, ‘Translation as nuclear arms race’, published in our November issue.

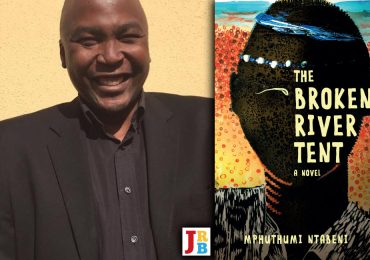

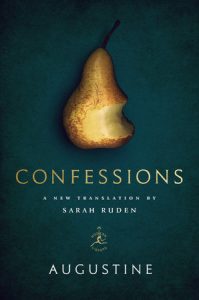

Confessions

Confessions

Sarah Ruden

Modern Library, 2017

From Ruden’s letter:

It is only in light of familiar gender politics that I can make sense of this rhetoric. This is the same male paranoia that bleats warnings of annihilation or castration—because a woman is daring to compete or achieve. I kid you not: Van Schoor is terrorised by my literary translation, with its impressiveness that he admits to: ‘Like escalation in the nuclear arms race, the proliferation of new, more powerful poetic ordinance may lead simply to all-round neutralisation.’ He can commend a woman translator, but only if she directs her efforts toward bowing to centuries of male mediocrity.

I am traduced. I feel I have been invited to a game of cards in which one is dealt an open hand, from a not-very-well-shuffled deck, and plays them in such a way as to score the most points against competitors dealt other, open cards.

I don’t stand a chance in this game, however, for Sarah Ruden has dealt her own hand. She holds the ‘trump card’, the card whose owner is never wrong, never has to consider criticism other than as vicious attack on herself, and is always a winner. People do not disagree with your ideas, if you hold the trump. They dislike you, probably because they are bitter, frustrated mediocrities, such as, we learn, I am. They don’t have their own principles, are only against your principles. They are the real victims.

I am surprised to be accused by Ruden of discouraging the study of languages and of ‘defending the glories of civilisation’ while only ‘really struggling to keep them wedged in [my] cramped little niche’. I remain stubbornly devoted to persuading South African students to study Latin and Greek and Classics and to dispense with the aestheticising posture that admire them for their ‘glories of civilisation’. I try to get them to situate themselves as inheritors of world culture, and participants in a constantly shifting tradition; to feel free to seize whatever they are willing to work for as their own.

Everyone at university—especially Anglophone ones, especially in polyglot Africa—should study language, ancient and modern, local and foreign, their own and someone else’s. Everyone should reject education as a system of intellectual patronage for the middle classes to preserve admission to the gardens of privilege. I do not think I am a gatekeeper and I do not feel it is for me to exclude anyone willing or that anything belongs to me to jealously guard. Too long have we fed culturally on a diet of worms in South Africa—how happy, then, that more institutions like The JRB are emerging. What an opportunity is ours, now that apartheid education, with its instrumentalisation of access to prop up hierarchy, and its mandates to civilise and conserve, has been consigned to the rubbish dump.

What I do expect of students is: do not take my word for anything. Learn the languages yourselves, go to the source. Work and play ceaselessly and critically, never stop reading, do not be put off by the inaccessible. Learning is a right, for which South African youth have heroically sacrificed.

Difficulty is often the point; the struggle to undo the sense of a text is indissociable as an act from tracing the meaningfulness of one’s own life. If, for instance, you are asked to review a new translation, do not judge it by the claims of the translator, but by standards you can account for, against other similar projects, and by transparent reasoning. Let it become an opportunity for reflecting on your premises and values. This is something like epistemic democracy at work; accountable and, at its best, respectful, with a strong sense of one’s own human folly. This, and not surrender to self-justification, is worth standing by.

I could offer, in reply to Ruden’s bid: I’ll see your ad hominem charges of sexism, killjoy elitism, and misogynistic abuse of scholarly authority and raise you, dog-whistle racism. But to lay this hand would make me the one stooping to ad hominem hyper-defensiveness. When a white American woman accuses a black African man, whom she doesn’t know, of laziness, incompetence and primitive sexism, is she playing her strong cards against tired, old, pathetic excuses for his native inferiority? Well, no matter, for she has the trump card.

To be clear, I do not think Ruden is racist (I have no evidence she is and if she were I would not care, it should be irrelevant here). I am trying to make a point about the ridiculousness of her rhetorical strategy. It is possible that I used the opportunity of a book review to try and hold back a woman; that I am a misogynist and do not think women should be translating Latin into American English. But then it is equally possible that I sincerely did not enjoy Ruden’s translation, that I found the claims she made of her maverick originality imprudent; possible that I thought that while her work had vigour it lacked subtlety, that the polemical character of her introductory essay was injudicious and its claims strong enough to invite special scrutiny. Just because I do not find her work in every way successful, does not mean that I find all the principles by which she explains her project to be wholly and terminally invalid. It is also possible that I preferred the work of Carolyn Hammond for the reasons I stated, and not because I like women to ‘bow to male mediocrity’, as alleged.

Ruden is right, Augustine did not go to Italy to study philosophy. I should have suggested that he went and participated in philosophical circles. Likewise, I did not review Ruden’s translation to offend her, but I reviewed it and offended her, which is a pity. As you see, I am no good at card games. But Sarah Ruden, if you are ever in the Eastern Cape, I hope you will look me up. I have laid aside a nice bottle of pear schnapps. I hope we can toast Augustine and have a good laugh at ourselves and these, our exaggerations, one day.

~ ~ ~

Publisher’s note: Van Schoor submitted a longer review essay of Ruden’s translation than the edited one that we published (the full-length version can be found here), which longer piece we sent to Ruden before she wrote her letter of reply.