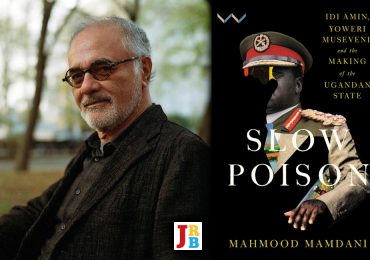

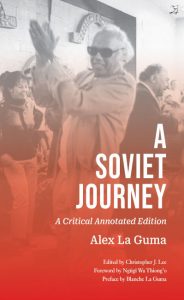

The JRB presents an excerpt from a new edition of A Soviet Journey by Alex La Guma: A Critical Annotated Edition, edited by Christopher J Lee, with a preface from the late Blanche La Guma, and a foreword by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

A Soviet Journey by Alex La Guma

A Critical Annotated Edition

Edited by Christopher J Lee

~~~

Foreword

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

He was not there in person—he was under house arrest back in apartheid South Africa—but Alex La Guma dominated the literary discussions at the 1962 Conference of African Writers of English Expression, held at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda. Among the attendants were some of the leading writers of the continent, and they included Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Christopher Okigbo from Nigeria, Kofi Awoonor of Ghana, and a group of exiled South African writers, among them Es’kia Mphahlele, Lewis Nkosi, Arthur Maimane, and Bloke Modisane. La Guma’s book A Walk in the Night had just been released by the Mbari Writers Club in Nigeria, founded by Ulli Beier among others. La Guma’s realism was often compared and contrasted with that of Chinua Achebe’s, whose novel Things Fall Apart had been published by Heinemann in 1958. It’s interesting that both novels had titles drawn from English literature—Shakespeare in the case of La Guma, and Yeats in the case of Chinua Achebe—reflecting the dominance of English literature in the education of the writers present. But the two texts were seen as mapping new directions in African literature in English, heralding the Africa emerging from colonial domination. Alex La Guma spoke to me and to this emergent Africa from the place of his house arrest through his words.

I met Alex La Guma in person for the very first time in Sweden at the 1967 Afro-Scandinavian Writers’ Conference held at Hässelby Castle, Stockholm. Those attending included Wole Soyinka (Nigeria), Albert Memmi (Tunisia), Kateb Yacine (Algeria), Tchicaya U Tam’si (Congo), and Dan Jacobson (South Africa). In the course of delivering the opening lecture ‘The Writer in Modern Africa,’ Soyinka made a reference to the African writer in some independent African country and who, in despair, was reduced to carrying guns and holding up radio stations.

It was of course a reference to himself, but it was Alex La Guma’s response that raised the whole question of the role of violence in revolutionary change. As a South African, he said he was prepared to run guns and hold up radio stations, because, whether as writers or common laborers, the situation called for fundamental change. I was struck by his coupling of writers and workers and by his speaking on behalf of the working class in apartheid South Africa. For him, the writer was a worker with a pen. In person, he dominated the discussion in Sweden much as his text A Walk in the Night had done at Makerere five years earlier.

La Guma was tall, serious, and focused, but once I did see another side of him. It was at a party held for us at some house in Stockholm. When some jazz music was put on, I saw Alex La Guma, on the floor, jiving. Yes, he could jive! He was free, the picture of one who loved life.

Six years later in September 1973, he and I would meet again, this time in Moscow on our way to the Fifth Conference of Afro-Asian Writers at Alma-Ata in Kazakhstan, then part of the Soviet Union. This meeting followed previous ones held in other capitals including New Delhi, Tashkent, and Cairo. Among those attending were Okot p’Bitek (Uganda), David Rubadiri (Malawi), and Lenrie Peters (Gambia). Our guide was the late Victor Ramzes who had done so much to translate African writing into Russian. It was during this visit that discussions began about La Guma returning to tour the Soviet Union and write whatever he wanted to write about it. I was also asked if I, too, would come back and do the same. The invitations were out there.

I never took up the offer, or rather, when eventually I did in 1975, it was not to tour the Soviet Union, but to go to Chekhov’s house in the Caucasus Mountains overlooking Yalta to complete my novel, Petals of Blood. That was also the last time I met Alex La Guma, but in a hospital in Moscow.

The last time I heard of him he was the ANC representative in Cuba, and then the loss, in October 1985. He never lived long enough to see post-apartheid South Africa, but he had no doubt that it would come to be, or rather he had seen and predicted it in his novel In the Fog of the Seasons’ End.

I felt his loss in a very personal way. I always felt him to be a kindred spirit. His spirit of hope lives on in the books he left us. He is a central figure alongside Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and others in the making and consolidation of modern African literature.

But I will always carry the image of the Alex La Guma whom I once saw jiving the night away in Stockholm, a year after his exile from the South Africa he loved. In his life and books, he struggled for a society in which all people could find their humanity. Joy in life was part of that humanity, and it comes through in his novels and memoir.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

June 2016

~~~

The Monday City

In the morning the sky suddenly became gray, and the mountains disappeared in mist. In the street below children in white shirts and red scarves were on their way to school. We did not have breakfast in the buffet because the morning queues were too long and took it in the restaurant of the night before, deserted now except for setting things out for the coming day. I settled for unexotic fried eggs and compensated with kefir boiled in the Ukrainian way. I had time to kill until eleven o’clock when I was to meet some writers at the local union, so my interpreter Larissa Borisovna and I went for a stroll.

Outside the hotel a sign announced that ‘season tickets for public transportation in Dushanbe will be available from March 1.’ In the square girls in cerise silk trousers passed, carrying briefcases. Colored trousers and traditional dresses in their multicolored patterns mingled with mini-skirts. Tyubeteikas, the embroidered skullcaps, made brilliant dots bobbing in the groups around the street kiosks.

On Lenin Prospekt the trolleybuses trundled past the pink-and-white apartment blocks, the elm and fir trees, heading toward Aini Square and the large Opera and Ballet Theater. In the square old men in turbans and long quilted coats dozed as the mist lifted and the sun came out and in the distance, behind the opera house, where they were advertising Madame Butterfly, the gray-brown hills came into view.

The offices of the railway workers’ Communist Party organization were located in a rectangular building fronted by a green lawn and elm trees, and from a window a young man stared with the usual curiosity at a visiting foreigner. A red-and-white billboard outside said: ‘Railway workers of this district pledge to increase output by 4.5 million rubles as their contribution to the current five-year plan.’

On a corner a group of muscular young girls in denim jeans waited to cross the road. They were members of a volleyball team arriving from an outlying village to take part in a tournament. They smiled rosily and explained that they were a mixture of workers and schoolgirls and then hurried to beat the lights, chattering and lugging their hold-alls, healthily nubile.

The veil associated with subjected Eastern women was nowhere to be seen, neither on old or young. The dark horsehair yashmak that covered the face and body has become a museum piece, but discarding it was a brave act in the early days of emancipation.

In old times women had been virtual slaves to their husbands, confined to their homes for most of their lives. All this had been sanctified by religion. Now they were equal citizens of the USSR and had the same rights as men in all spheres of economic, cultural, and socio-economic life.

In the 1920s, the counter-revolutionary, fanatical bands of basmachi, backed by feudal patrons, had often beheaded women who had thrown off the veil. Now the colorful national costumes prevailed, but the yashmak was gone forever.

Dushanbe lay in the Gishar Valley among the mountains in the long May morning. For many centuries the trade routes connecting Central Asia with India passed through here. Camel caravans, swaying heavy with goods for trade, set out from Bukhara on Friday and on the following Monday made their stopover here for the fair that would attract villagers from the surrounding hills. Those fairs were called ‘Djushambe‘ which is Tajik for Monday, and the name now designated the collection of adobe huts that made up the village that was to become this capital.

When Soviet power came to the Pamirs in 1922, the population of Djushambe Village had been about one hundred, occupying a scattering of huts surrounding the tea house and an opium den. In this place there are now the library of the Republic with two million books and ancient manuscripts, and all the buildings in traditional Tajik and Russian style. The population had grown to 436,000 with 40,000 students attending the university, the agricultural institute, the polytechnic and teachers’ training college, and the medical school. Another sixteen thousand young people went to twelve technical schools for specialized secondary education, and the city’s one hundred general educational schools were attended by ninety thousand children.

Here and there one came across one of the twenty research institutes where young and middle-aged in the embroidered skullcaps, traditional dresses, or modern casuals and suits studied astrophysics, seismology, chemistry, or Orientology among the rose beds and orderly parks. The textile-machine factory manufactured equipment for Europe, Tunisia, and Lebanon.

One thought of Alexander’s tired troops in the mountain valleys, the tinkle of camel bells, the mullahs who had been the few endowed with literacy, the raiding basmachi bands, all retreated now behind the veil of the dusty past.

When we got back to the hotel Massud was waiting with a car to drive us around. The driver was a young man in a blue denim suit in the style of American cowboys.

Writers

‘Many writers here devote their works to the history of Tajikistan,’ somebody said, ‘mostly, to the revolutionary and post-revolutionary period.’

Everybody needed to say something. In the company were comrades from the Afro-Asian Solidarity Committee and the Writers’ Union. I remember a poet named Mirsaid Mirshakar (Lenin in the Pamirs), comrades Karimov, Rakhim-zadeh, Ikrami, Mukhumali Rajad. The Turkic—or Arabian?—names lay romantically on the tongue: one thought of medieval Moors, Harun al-Rachid, Saladin. But this was Soviet Tajikistan, the camel trains had gone, and the Aeroflot flight from Moscow came in regularly; the railway through the mountains to Dushanbe had been constructed in 1929, but helicopters crossed the ranges too; the oranges came by ship and train from Morocco.

‘Also books about the Great Patriotic War.’

More than fifty thousand Tajik officers and men won orders and medals, and forty-nine became Heroes of the Soviet Union. The war had also brought large industrial enterprises. During those years collective and state farmers delivered over 507,000 tons of raw cotton to the state, along with grain, meat, and dairy produce. The Soviet government decorated 102,000 Tajik men and women for their contribution to the war effort. About 120 million rubles donated by the people went into building tanks and aircraft.

‘They also deal with modern topics,’ somebody else said against the clink of mineral water bottles, cups, and the rustle of the wrappings from the chocolates that came with the coffee. ‘Like the building of the hydroelectric station on the Vakhsh River. That forms the background to several works. But we haven’t produced any great books yet, a lot of poems and novelettes, but no great books. The problem might be that when a writer visits some great project for material he becomes the slave of only what he sees and so he can’t perceive everything.’

Tajiks have a great tradition of folk dancing, instrumental music, solo singing, and poetry. Prose, drama, children’s literature only came with the Soviet era, as did cinema, symphony music, and the professional theater.

‘At first it was difficult to reconcile traditional ideas with modern achievements,’ a woman in the company said. ‘That applied to almost everything. There was a time when people were afraid of electricity, of the radio. Now there are even TV sets in the mosques.’ She laughed, ‘Old people are no longer afraid of planes—they prefer flying to trains.’

Both Tajik and Russian are used in schools. The children can go to a Russian first-language school or a Tajik first-language one, the choice belongs to the children and parents. At official functions Tajik, Russian, and Uzbek are used with simultaneous translation: this is provided by the constitution. The difficulty is to find teachers who speak and teach all the languages, as well as additional foreign languages like English, French, and Arabic.

The conversation inevitably drifted back to the emancipation of women; nowadays it was unavoidable, and after all this was International Women’s Year. In Tajikistan’s parliament there were 33 percent of women and 50 percent in local Soviets. Two comrades present mentioned with pride that each had a daughter at the State Art Academy, studying to be composers of music.

Even among the writing fraternity the politeness and ceremony of Soviet society had not been forgotten. I was presented with a fiftieth anniversary commemorative medal, and everybody shook my hand, bidding me welcome back at any time.

Against the background of the hazy mountains the monument to Rudagi, turbaned, bearded, and robed like a figure from Mosaic times, gestured with a stone hand as if he were reciting. But at my hotel I had only a volume of a later work by another from across the border, the Kazakh Abai, and the 1000 B.C. Sanskrit epic, the Ramayana, in a condensed English version. The stone face did not seem to mind: they were, after all, of the same profession.

The mist had lifted, and we were shaking hands by the rose beds, and the chinar trees were bright green in the sun opposite the Friendship House. We were joined by a Tajik war veteran, who had fought on the Byelorussian front. His jacket hung with medals.

~~~

- Alex La Guma (1925–1985) was a prominent South African writer and activist.

- Christopher J Lee is Associate Professor of History at Lafayette College.

~~~

Publisher information

In 1978, acclaimed activist and novelist Alex La Guma (1925—1985) published A Soviet Journey, a memoir of his travels in the Soviet Union. This work remains one of the most comprehensive first-hand accounts of the USSR by an African writer, offering a unique African perspective on the Soviet system and its implications for South Africa’s future.

La Guma’s book, a valuable document from the anti-apartheid and Cold War eras, presents the Soviet Union as a symbol of justice through socialism—a vision that evolved with the USSR’s collapse. This new edition, the first since 1978, revives this perspective, showcasing how La Guma and other activist-intellectuals viewed the Soviet Union as a model for self-determination, decolonization, and development.

Christopher J Lee’s introduction contextualises La Guma’s work within the broader Black Atlantic and Third World frameworks, offering insights into African literature and global intellectual exchanges.

A Soviet Journey will engage readers interested in African fiction and non-fiction, South African history, postcolonial studies, and radical political thought.