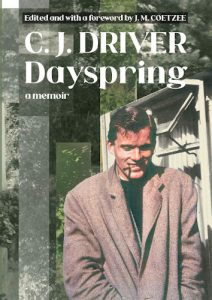

The JRB presents an excerpt from Dayspring, the forthcoming memoir by CJ Driver, edited and with a foreword by Nobel Prize-winning author JM Coetzee. Out in South Africa on 1 July 2024.

Dayspring

CJ Driver (Edited by JM Coetzee)

Karavan Press and uHlanga Press

I had given up residence in Smuts Hall in part because I thought it would be cheaper taking a room in Rondebosch. While I quite liked being on my own, my room was small and uncomfortable, stifling in summer and cold and damp in winter. I wasn’t meant to do any cooking, though in fact I did smuggle in a heating ring, and I had to share my landlady’s bathroom and lavatory upstairs. At first, I took my evening meal in an Italian restaurant in Rondebosch, which did a special deal whereby one got the plat du jour for relatively little. Then I discovered that the refectory at the Students’ Union did a special three-course lunch at a very low price—it was in fact one of the quiet subsidies meant to make life easier for students from the townships. So I had lunch on campus, and in the evening cooked myself a bowl of pasta with grated hard cheese.

But after the nasty experience of Bornholm disease, I decided I should try to find somewhere less damp to live. Adrian Leftwich, who had succeeded John Shingler as president of NUSAS and with whom I was friendly, asked if I would like to share the rent of the White Cottage with him. Although the presidency of NUSAS was a paid position, the pay was a pittance. The White Cottage was owned by an Indian family who lived unobtrusively in a quiet lane behind the cottage; one of its advantages was that it was as yet unaffected by the Group Areas Act, which designated certain areas for particular racial groups. That suited us politically. Leftwich was himself an interesting young man, literate, energetic, a committed liberal, deeply interested in politics, very popular on campus; he was charming, a good actor and a remarkable debater, even by the standards of stars like Rubin and Bromberger.

In my capacity as a member of the national executive, I had accompanied Adrian Leftwich on one of his presidential tours to the Eastern Cape, visiting Rhodes University in Grahamstown and the University College of Fort Hare in Alice. Fort Hare numbered among its ex-students some of the most famous politicians in Africa, not only in South Africa. NUSAS had in fact been banned from the Fort Hare campus by the principal, backed by the security police. The security police in Alice were led by an especially nasty and brutal officer named Hattingh, who was constantly on the lookout for political intruders.

The opposition of the college’s principal, and the ban on NUSAS, counted in favour of Leftwich and myself, since liberals were not well regarded among students at Fort Hare, ‘liberal’ being synonymous with ‘half-hearted’. We had excellent contacts there, two of whom became lifelong friends. Stephen Gawe, son of the Chaplain-General to the ANC, would later emerge from detention and then imprisonment to join me at Trinity College, Oxford. Winston Nagan, son of an Indian headwaiter from Port Elizabeth and an Afrikaner mother who were separated when the Immorality Act came into force in 1949, was at Brasenose College, Oxford, while I was at Trinity. Both had fine subsequent careers: Gawe became, post-apartheid, a senior member of the South African diplomatic corps; Nagan became professor of international law at the University of Florida.

A third friend, though perforce I was out of touch with him for many years, when I was in exile and he was a lawyer in the Transkei, was one of the more remarkable young men of those days: Templeton Mdlalana, a tall, powerfully built, brilliantly articulate man, strong in a crisis, unflinching under pressure.

The three were not just outstanding students at Fort Hare, but were typical of the range of talent, courage and intelligence to be found there.

Leftwich and I arrived in Alice after sunset, and were taken to the first meeting place, a slight declivity in the middle of the rugby pitch. When police cars tried to track us, we all lay flat. Their lights swept over the field and showed it as empty.

We discussed holding the meeting in the university itself, at midnight. One of the students had a spare set of keys and would open a lecture room for us. Because of informers, meetings were never announced beforehand. Five minutes before the starting time, word would go round the residences that there would be a meeting, and nearly everyone came. Indeed, suspicion fell on those who did not.

The Fort Hare students were almost without exception brilliant debaters: political debate was a favourite pastime. Moreover, many (though by no means all) were Xhosa-speaking. AmaXhosa culture (for men at least) had a strong emphasis on democratic debate within the tribal structures. Young men were encouraged to get to their feet among their elders to argue a case. Nonetheless, even in that formidably aware audience, Leftwich’s performance that night was the best I had ever seen: passionate, witty, sharp, spontaneous, fluent. He did get some help: when the questions started from the floor—many of them adversarial—a friend in the front row would occasionally write in big letters on a page of foolscap, and hold it up so that Leftwich could see it, a helpful bit of guidance as to the political affiliation of the questioner: NEUM—Non-European Unity Movement, basically Trotskyite—or PAC—or in one case AGENT PROVOCATEUR. A year later, when I was back in Fort Hare as Leftwich’s successor, and facing a similarly aware and politically tricky audience, one of the messages held up to help me deal with a dangerously provocative question about the use of armed force was INFORMER.

The PAC questioners were especially virulent. One launched a fierce, though witty, attack on NUSAS and on Leftwich personally. What right did he, a white man, have to come to Fort Hare to tell them what they should think? His job wasn’t to talk to black students; it was to talk to his ‘white fathers, Verwoerd and Vorster’ (at that time Prime Minister and Minister of Justice, respectively). Instead of defending himself, Leftwich attacked: let the questioner then deal with his own ‘black fathers, Matanzima and Sebe’ (two of the most hated and despised leaders in the Transkei, then in its guise as a Bantustan). The timing was perfect, the point brilliant, especially so as the questioner, for all the virulence of his views, had family connections with the despised leaders; the audience was duly appreciative.

I saw another side of Leftwich in his love of ‘schlentering’. ‘Slenter’ is a Dutch and Afrikaans word, meaning trickery or knavery; the ‘ch’ probably reflects the Yiddish presence among the diamond miners—the original application of the word was to fake diamonds. Its use in South African student politics was as a verb: to schlenter someone was to run rings around them politically, to outfox them, to fool them. Leftwich was a past master at schlentering; sometimes, watching him do it could be almost amusing, but to be on the receiving end was not pleasant.

Not a political innocent myself, a few months after I ceased sharing the White Cottage with him, I watched Leftwich schlenter me totally in an election to office of the SRC. I thought that a bid for the presidency of NUSAS—which I was beginning to contemplate—might be easier to mount if I were vice president of the SRC, not merely secretary. The unofficial liberal caucus held a meeting beforehand to sort out the nominations and how we would vote, to make sure we didn’t split our ranks, some of the liberals preferring sensible Jill Jessop to dangerously outspoken Jonty Driver. Consensus was that the president would be the popular and progressive Hertzel Melmed, vice president Jonty Driver, secretary Jill Jessop. Leftwich made a note of the decisions we had reached, decisions which he had certainly agreed to. Carefully—since I had learned not to trust him—I pocketed the list at the end of the discussion.

At the meeting itself, almost the reverse of what had been agreed by the liberal caucus occurred. Jill Jessop was nominated as vice president and elected. At that late stage of the proceedings there was no way in which I could summon up a nomination of myself, nor any support. I remained just secretary.

Though I had clearly been schlentered, I thought that for once I could prove Leftwich’s dishonesty. I produced the note with the list of officers that he had written in his own hand and passed it to him. He passed it back to me, grinning. There it was: ‘Pres HM. VP JJ. Sec JD.’

Adrian Leftwich had at one stage been very close to Neville Rubin, indeed was regarded as Rubin’s protégé. He was best man at the marriage of Neville Rubin and Muriel Lewsen, though later they fell out. His father was a gentle, white-haired GP, apparently much loved by his patients. His mother was altogether spikier and livelier. I already knew that the relationship between mother and son was awkward: Adrian refused to live at home, and paid his own way through university by teaching in a cram school. Just how awkward the relationship was I discovered when I shared the cottage with him. Mrs Leftwich called to see him when he wasn’t at home. I invited her in. Would she like to have a coffee, or to telephone Adrian? No, she said: she wouldn’t come in, she just wanted to see where he was living; Adrian wouldn’t want her to be there.

When I told Adrian that evening his mother had called, he was enraged, first with me, then with his mother. He accused me of encouraging her visit; he said she had no right to come—what did it matter to her where he lived? Reasonable responses were of no account.

I had come across difficult relationships between parents and children before (after all, one of my close friends was John Coetzee, though his way of dealing with his problems was silence), but never before had I come across such apparent loathing and anger of a child towards a parent.

It wasn’t as if the cottage was comfortable to share. It had only two rooms. Adrian took the bedroom, while I slept in the sitting-room. But since he didn’t like my sleeping there while he was at his desk, I couldn’t go to bed until he had gone to bed, and I had to be up as soon as he got up. There was no desk for me to work at. He suggested I could work in his bedroom while he worked in the sitting room, but the bedroom was very dark and did not have a table. I had no car, so getting to the university meant walking, unless Adrian would drop me en route to his office in the city; but I grew less and less happy about being dependent on him when he was so grudging. Only when he was away from Cape Town on NUSAS business was the White Cottage comfortable to live in.

When he came back from his travels, he asked me if Jann had been visiting me in his absence. Of course, I told him. He didn’t like her coming to the cottage, he informed me. Why? He couldn’t explain, he just didn’t like her visiting, whether he was present or not. I informed him she would come whether he liked it or not—after all, I was paying half the rent.

Quietly, I began to search for somewhere else to live. While I still had a degree of admiration for Adrian and his talents, his psychological frailties were beginning to seem irksome and possibly even dangerous—how dangerous neither Jann nor I had any idea yet.

I was offered a share of a small house by two of the members of the editorial board of Varsity, Roger Jowell and Rick Turner, both younger than me but great fun and very bright. Although he had made me feel unwelcome, Adrian was furious with me for ‘letting him down’. I could do nothing but shrug. What little remained of our friendship was never restored, even after I succeeded him as president of NUSAS.

Roger Jowell was the second son of a wealthy and hospitable Jewish family who lived in the prosperous southern suburbs of Cape Town. His elder brother had been president of the SRC and would become president of the Oxford Union too. I knew little about Richard Turner, though he was an interesting person, much given to political philosophy and arguing. He had red hair, which predisposed me illogically in his favour, since my brother Simon had red hair too. The main problem with the house was that it was due to be demolished to make way for a block of flats. It was also a little too far away from the university. However, the lease was regularly extended, and we stayed there happily for many months. All shape and size of friends were welcome there; since the house was to be demolished, one didn’t have to worry about the fabric too much; the landlords were invisible; and it was a good place for a party. We had some lovely parties there—we discovered that a cheese fondue with quantities of white wine was an easy way of entertaining hordes of people. Since Rick was the tidiest and had the nicest room, it was his bedroom that was used most often for parties, and his girlfriend Barbara, later to become his wife, was a cheerful hostess.

~~~

- CJ Driver, always known as Jonty, was born in Cape Town in 1939. He was the author of ten collections of poetry, five novels, and numerous works of non-fiction. President of the anti-apartheid National Union of South African Students in 1963–64, Jonty was detained in solitary confinement by the security police, subsequently fleeing to England. He became stateless and his writings were banned. His professional life was spent as a schoolmaster in Hong Kong and England. Driver died in England in 2023. Since then, he has been hailed as one of South Africa’s major modern poets.

- JM Coetzee was born in Cape Town in 1940 and studied at the University of Cape Town from 1957 to 1961. Between 1972 and 2000, he held a series of positions on the staff at UCT. His writings have won numerous awards, including the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2003. He currently lives in Adelaide, South Australia.

~~~

Publisher information

Dayspring is a recollection of CJ Driver’s South African youth—his childhood as a reverend’s son in Kroonstad and Grahamstown (now Makhanda) preceding his extraordinary student years at the University of Cape Town, during which he edited the student newspaper Varsity and became enmeshed in radical student politics.

As president of the anti-apartheid National Union of South African Students, Driver was detained by the security police, tortured and imprisoned in solitary confinement in Cape Town. Even after fleeing to England, Driver remained a bête-noire for the apartheid authorities, with ex-president BJ Vorster keeping personal notes on Driver’s activities.

But all that comes later in his life. Dayspring is a tender and deeply personal book, offering an intimate picture of a family coming to terms with the losses of the Second World War. It is the story of a father and son recognising their differing beliefs, and of a young man navigating the joys and pitfalls of romance. As a direct descendant of the 1820 Settlers, Driver examines the contradictory beliefs and institutions of the South Africa he grew up in—particularly its boarding schools—with unique insight and humour.

Throughout the reader discovers the moments of inspiration, failure and literary exchange that were crucial to the development of Driver’s fiction, celebrated internationally during his lifetime, as well as his poetry, which, even before his death in 2023, has been lauded as one of the most significant bodies of work by a modern South African poet.

In Dayspring, we are witness to the formation of a sensitive, incisive intellect; someone who did not simply engage with the world through literature, but faced up to it, too. This is an extraordinary book.

RSVP to your invitation to the Jonty Driver memoir: Lesley and Maeder Osler have much pleasure in accepting your invite. We will possibl also be bringing Gillian Vigne. Thankyou!

Neville and Muriel Rubin have great pleasure in accepting your invitation. We look forward to this event while sadly missing Jonty’s presence.