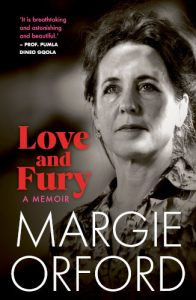

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from Love and Fury: A Memoir by Editorial Advisory Panel member Margie Orford.

Margie Orford

Love and Fury: A Memoir

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2024

The murdered girl from Walvis Bay, who I called Constance, haunted me because her murder had pierced a protective illusion of mine—and that of many other women too, I think. She was my doppelganger. She was beaten to death, but it could just as easily have been me, which is one step away from thinking if it had been me, then she might still be alive.

I was burdened with the feeling that she had gone in my place, a form of survivor’s guilt. We had done the same things, after all, gone to the same places, walked the same streets. There is no reason why one girl is murdered, and another is not. It’s a matter of wrong place, wrong time, and the bad luck of running into a bad man.

I entwined Constance into my fiction to honour her ghost and manage my fear, my misplaced guilt. Fiction gave me an imaginative power over the lives and deaths of women that journalism did not. I dealt with the haunting effect of Constance’s murder (and my not-murder) by changing the ending of her life. To do this, I made Constance the twin sister of my heroine, Clare Hart. Though neither sophisticated nor original, this literary gambit gave me a way to examine how violence divides women from themselves.

My cerebral and impenetrable heroine, Clare Hart, could walk by herself at night with impunity, and as a schoolgirl she does this. But her twin, Constance, cannot. Clare, who, one evening, was returning to boarding school from an illicit tryst, comes across her battered, left-for-dead twin, who had tried to follow her, and she ends up saving her sister’s life. Constance is her other self, or her body-self. Clare’s determination to bring male perpetrators to justice determines her career as a journalist and profiler. My fictional character’s resolve reflected my own.

But fiction only goes so far. I could bring Constance back to life, but only as a reclusive Lady Lazarus. The damage and the scars women carry cannot be erased, but they can be understood and avenged. And so, the resolution of my first novel, a serial rape-femicide thriller, is achieved through the actions of a character who survives a brutal assault and seeks redress at Rape Crisis—a Cape Town organisation to which I personally had referred several women and girls.

I knew the centre well. It was in Observatory, round the corner from where I’d lived as an undergraduate, and for which, in my student days, I had done fund- and awareness-raising. I met with the director, who had been a fellow student. She was as thoughtful and steadfast as I remembered her to be. I found her informed belief that a woman’s life, if interrupted by an assault, could and would go on, restorative. She and the women working with her did their best for the rape survivors who came for counselling and then, with varying degrees of success, pieced their lives together again.

This talking cure, this reshaping of an obliterating experience by means of a story that could be told—certain elements foregrounded, others left out—seemed to me to return a sense of agency and control over an experience that had stolen a woman from herself. Was it this telling and reshaping, I wondered, that helped alleviate the sense of shame that took up residence in the victim, seemingly at a cellular level? As if shame was somehow a psychic virus transmitted by the perpetrator. I came to know the divide, experienced as a rupture in time, between a woman’s sense of who she is prior to the attack and afterwards: the shattering of that self.

That break in time is at the heart of the traumatic experience, as is the compulsive return to the experience. The psyche tries to stitch together the tear in linear time and to restore the woman to herself, intact. But this is not possible. We cannot go back, we cannot make things unhappen. But we can go on, and that is what we, as women, try to do.

Male violence makes women police what we say and where we go, but to reclaim our streets, homes and bodies, we must break the silence. Speaking out is one aspect of this, legal redress another. Rape Crisis volunteers were available to accompany survivors to court, and I once accompanied a woman and sat beside her as the rapist’s lawyer shredded her account, her integrity and her reputation. The director was a proponent of pressing charges, even if the justice system—cops, prosecutors and judges—rarely believes women, and frequently blames them for the crimes committed against them.

Rape Crisis, with its solidarity, kindness and belief in women, found ways of converting hopelessness into resilience, and anger into action.

And I was angry. To survive as a woman in South Africa, I had to be angry; just being a woman means you’re afraid a lot of the time. Most of all, though, I needed to be a feminist to channel my fury and fear into a transformative politics.

I held poetry workshops with rape survivors, which helped me understand ways in which women are able to reject the shame of rape, returning it to its rightful place: the perpetrator. With the women’s permission, I wove much of this into my fiction, transforming their stories into a broad canvas of crime committed against girls and women in my country.

Two things struck me about rapists I’d encountered in my research—their ordinariness and their shamelessness, minimising their own crimes. One man rattled off a list of things he had done on the day of a rape: woke up, had cornflakes for breakfast, spoke to a friend on the phone, watched TV, ‘had sex with’ a girl, hung out with friends, watched more TV, went to bed. The rape—which he did not name as such—was no more or less consequential than anything else he had done that day. And so his sentence, several years in prison, seemed to him totally out of proportion to something that was, to him, as inconsequential as eating breakfast or having a beer. For the victim, however, it had been a day of trauma, forcing her, like so many others, to spend months or years or forever dealing with the fallout of a catastrophic event.

The shamelessness and the solipsism of that rapist transfixed me. It was as if, through the malignantly transfiguring power of his act, he was able to rid himself of his own shame and vulnerability—which, unable to integrate, he projected onto his victim. She, vulnerable at home and also outside of it, then absorbs and carries the perpetrator’s shame as if it were her own.

~~~

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Margie Orford is an internationally acclaimed writer. Her Clare Hart novels have been widely translated and led to her being described as South Africa’s ‘queen of crime’. She is also an award-winning journalist, and writes regularly about crime, gender violence, politics and freedom of expression, and literature. She was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship in 1999 and has Masters in Comparative Literature from the Graduate School of the City University of New York. Orford now lives in London and is an honorary fellow of St Hugh’s College at Oxford. She is the President Emerita of PEN South Africa, was on the board of PEN International, and is a co-author of the PEN International Women’s Manifesto. Follow her on Twitter/X.

~~~

Publisher information

‘This book kept me alive.’

Love and Fury is the compelling and intimate account of the life, loves and furies of Margie Orford. In this brave memoir, the renowned South African crime writer divulges some of the harrowing experiences that have shaped her life and influenced her writing.

Through sexual assault, divorce, depression and personal loss, Orford illuminates the trauma she has navigated. Tender and courageous chapters vividly recall memories of what she has been through as a woman, mother, wife, feminist and ambitious writer.

Love and Fury shows why trauma in our past can have such an enduring and debilitating effect on women’s lives. It also unpacks the healing power of love, creativity, courage and self-reflection, ultimately offering a profound message of hope and joy for any woman who has ever questioned themselves, their trauma and who they are in the world.

This book is every woman’s love and fury.