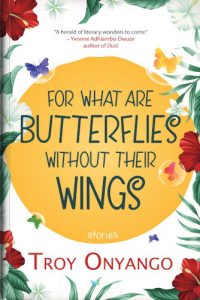

The JRB presents an excerpt from For What Are Butterflies Without Their Wings, the debut short story collection from Troy Onyango.

For What Are Butterflies Without Their Wings

Troy Onyango

Masobe Books, 2022

Whirlwind

Only after nineteen years have gone by does Nikesh think of going back to Kisumu, the city of his birth, whose name tastes like bile in his mouth and whose existence he banished from memory. When Tara, his sister, asks him on Skype if he remembers Sam, and he says of course he does, she informs him that Sam is no more. He moves his face away from the camera, blinks away the tears that have started to gather in his eyes, and asks Tara when the burial will be. She tells him she is not certain, but it might be over the weekend. He tells her he will be coming for the funeral. He does not tell her that he is sorry he cannot come because he is busy with his work at the Telecommunications Corporation like he said when his father died of a heart attack three years ago, or when his mother died of a heart full of sadness a year later.

He wakes up the next morning before his alarm goes off and turns to his wife who is fast asleep with her arm tucked under her beautiful, oval face and her elbow protruding towards him. Cautious not to wake her, he kisses her on the forehead, inhaling her scent from the lavender and chamomile soap she uses, and he slowly gets out of bed. He packs a small bag containing two shirts, a pair of jeans, toothbrush, underwear and cologne. He heads for the airport, ignoring the sounds of the streets of Mumbai that seem to be urging him to stay.

On the plane, he sends an email to his boss informing her that he will not be able to come to work for the next few days; he does not give any reason. He looks outside the window as the plane taxis on the tarmac. He ignores the burly woman with a swollen lower lip asking him if he is also Kenyan–Indian. He closes his eyes and falls into a deep, tranquil sleep like someone on a large dosage of anaesthetics. He dreams of nothing; only black all around him.

Eight hours later, he emerges on the other side—the connecting flight from Nairobi to Kisumu having been nothing but a blur—and he pushes through the throng of people waiting for their loved ones. He finds the taxi driver, a middle-aged man with bushy eyebrows and a noticeable shorter left leg, holding a cardboard with the name NIKI written on it in neat block letters. No one has called him that in a long time.

In the backseat of the taxi, he rests his head on the old worn-out leather, feeling both exhausted from the flight and exhilarated to be back. He closes his eyes, but he is unable to sleep, so he looks outside through the window of the car and notices that the city still has the low buildings covered in thick layers of dust, still the same even after all these years. He is happy and disappointed at the same time. He remembers having seen cities that shed their skins and became new ones in less than six months. He tries to forget the ones that get buried in a day from war or deserted by their inhabitants. He sees children of school age playing football by the roadside, the ball made from old newspapers held together with used drinking straws bouncing off the dust. When the children spot him, they pause their game to wave their hands caked with dirt at the car and shout, ‘Mzungu!’

He wishes he could stop the car, walk over to the playground and tell the children, ‘I am not a white man. I was born here, like you. I grew up here.’ But it is too late, and the car is going past the flyover, the large concrete slab casting a shadow over them. He registers the slight darkness in the car and remembers that there was no flyover at this same place when he left, no darkness in his father’s blue-and-white Toyota that took him away. He knows things have changed.

His phone rings, and when he takes it out of the breast pocket of his coat, he looks at the screen and covers it with the palm of his hand as if to stop it from ringing. It rings again and he notices the driver’s furrowed eyebrows as he looks at him through the rear-view mirror. Eventually, he slides his index finger on the green button, and his wife’s face, alongside those of their three children, appear on the screen. She tells him she has been trying to reach him since this morning and asks him where he is, and why does he look like he is in a kidnapper’s car, but also is he okay because his boss called to ask if everything was fine at home, but she did not even know what to tell her. He waits for her to ramble on, knowing so well that this is how she speaks when anxious or agitated. When she is quiet but still breathing loudly, he tells her, ‘I’m in Kenya.’

She is quiet for a while before she says, ‘Nikesh, what are you doing there?’

‘Baba is in Kenya?’ Rajesh, the oldest child asks.

‘Shh Davish, let me talk to your father,’ she snaps. ‘Kenya? Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I’m visiting an old friend.’

‘You told me you haven’t been there in so many years. Not even when … Is everything okay? Is your sister okay? When did you plan this?’

‘Yes, everything is okay. I did not plan it. I bought the tickets last night. I’ll explain when I get back.’

He can tell she is restraining herself when she stays silent, smiles and asks if he carried everything he needs, and tells him that oh, he should take good care of himself. He listens with a false sense of interest and exhales loudly then tells her that he is tired and promises the children that he will call back when he gets to the house, before they go to bed. The youngest girl’s oval face—just like her mother’s—fills his screen, and in a voice so shrill and sharp like a cricket’s she says, ‘Baba, we love you.’

Nikesh does not respond.

The car comes to a sudden stop. He sees that he is outside his childhood home, and the memories start flooding back as if keen to overwhelm him, but he shoves them to the side as he has done every day for the past nineteen years. He gets out of the car, stretches his arms wide and yawns. He walks towards the unlocked gate, pushes it wide open and gets inside. A dog barks viciously as if to remind him of the fact that he is an intruder, and he wonders when his parents (before their death) or sister decided to get a dog. He raps his knuckles on the steel door and hears the jingling of keys and the screeching of the ungreased hinges as the door swings open. Tara appears in the frame. She stands there—eyes and mouth wide open, motionless—in disbelief that it is really him. He hugs her, and she bawls on his shoulders, her cries sounding to him like a distant muffled scream.

‘Niki, brother, welcome home,’ she says, but all those words sound alien to him, as the dog’s barking swallows them.

The taxi driver honks from outside the gate, and Nikesh remembers he still has not paid the fare. He tells Tara about it and informs her that he forgot his bag in the car. They both laugh in a dry crackling sound that attempts to reach through the space left by time but fails. He walks back outside, apologises profusely to the impatient driver as he hands him a folded five hundred shillings note from the money he changed at the airport. He reaches back into his pockets again and tips him an additional two hundred shillings. He apologises again and the driver hands him his bag, assures him that everything is okay and drives away. He holds his waist, with his bag dangling on one arm, and watches the cloud of dust at the tail of the car as the wind blows through his well-oiled hair. Still smiling, he turns to face the house and realises that the champagne-pink paint his mother once insisted on has peeled off the walls, and the tiled roof his father always wanted is almost sinking.

~~~

Three hours pass and they have talked about almost everything there is. At dinner, Tara puts before him a plate with goat curry and naan, and they eat in a deafening silence. The monochrome photos of their dead parents watch over them, everything unmoving apart from the eyes that animate when light from the fluorescent bulb strikes them. He wonders if both of them are judging him for not showing up at their funerals. He feels a lump in his stomach and tells Tara that he will eat the rest of his food the following day. She asks him to try to eat some more to regain the strength from his long journey. When he declines, she sighs the way their mother used to when they refused to eat her food. She calls the maid to take the plates away.

The maid appears at the door and asks him whether he is done eating, and he nods and thanks her. He watches her walk away and remembers her from his childhood when she was a young girl around his age and her mother was working in this house. He wonders why he did not recognise her. Tara moves closer to him and whispers, ‘Surely you remember Josephine, right? Her mother was our maid.’

‘Yes, I do. She’s grown but hasn’t changed much,’ he says.

‘Ah, she is Sam’s wife.’

He feels the punch in his stomach where the lump formed, and the pain spreads all over his body, intending to consume him from within. He drinks a glass of water, tells Tara goodnight and goes to his bedroom. There, he finds his things intact as if he never left, as if he has always been in that room. He does not find even a thin film of dust on the books he loved to read as a child, and he knows that both his sister and mother worked hard to keep his memory intact. The absence of change, supposed to make him happy, instead saddens him, and he lies on the bed, which creaks slightly with his weight. For the first time since getting back, he feels a heaviness in his soul and wonders if the universe conspires to preserve the things that cause so much hurt.

He cups his face in his palm and cries.

When the whole house is dark, he hears the dragging of feet in the hallway and wonders what Tara, who has always been scared of darkness, is doing outside his room. The footsteps grow louder and louder then stop right in front of his door. He stays still and waits. He can tell that it is not Tara but the maid, Josephine. The knock on the door terrifies him even though there is nothing to be afraid of, and he clears his throat and asks her what she wants.

‘Bwana, karibu nyumbani,’ she says, but something about the way her voice is hoarse and scaly when she welcomes him back home makes it sound like she is telling him to go far away, back where he’s come from.

He does not respond, and the footsteps are audible again, growing loud then faint as the kitchen door squeaks when it closes. He stares at the ceiling in the dark and hears nothing. The world is completely silent, and it makes him realise how his life in Mumbai has never been this silent, not even for a single moment. He closes his eyes.

~~~

In the morning, he wakes up and takes a few minutes to register his new environment. He listens to the sounds of the house. From the clanking of plates, cups and spoons, he knows that his sister is making breakfast, and the sound of water gushing from the tap outside his bedroom tells him that the maid is washing the dirty laundry. The sun pours in through the louvres and he pulls the covers over his toffee-coloured torso. He hears the birds sing as if they too are part of an entourage to welcome him back home. He deliberately blocks out the sounds of the cars passing right outside the gate and the ohangla music from the new café built next to their house.

Nikesh gets out of bed, walks down the corridor, into the bathroom where he leans on the wall and watches the steam rise from the half-filled tub. He gets inside, the tub filling up with the space occupied by his body, and the water spills on the linoleum floor. He paddles the water slightly with his hands, spreading his palms open so the water can slip though, and the memory of how he used to pretend to swim in this same tub comes back to him. He laughs at how ridiculous it is that he is not able to fit in the same tub.

He steps out of the bathtub, the water pooling into a puddle at his feet. He ties a towel around his waist and heads back to his room to change into fresh clothes—a purple shirt and khaki pants. Then, he walks out of his bedroom and sits at the dining table where breakfast of roti and lentils is ready. There are also pancakes and sausages, which he chooses to eat. While eating, he notices that the table is wobbly with one leg slanting as if it wants to fall. Suddenly, he remembers a time when his father was around, always walking with a hammer in his hands and nails in the shirt pocket, fixing everything including people’s lives.

For most of the day, he sits in front of the television watching the news and he wonders when the country’s political landscape changed so much. He laughs at the foolishness of the politicians inciting their supporters to violence and tells his sister, ‘Back home, they are just as stupid! Always inciting people against the Pakistanis.’

Back home.

He only catches it after he has said it, and he remembers that the past nineteen years have been spent always thinking of this same house as ‘back home’.

The maid—he has to learn to tell himself not to call her by her name, Josephine—appears at the door as if summoned and asks, ‘Mnahitaji chochote?’

He turns to look at Tara, and they both shake their heads saying they don’t need anything. Josephine still stands there, waiting. Tara asks her what she wants, and Josephine reminds her that she had asked for permission to go to the morgue. Tara tells her she can go. Nikesh stirs in his seat and remembers that it is the reason he has also come all the way. He offers to drive Josephine in Tara’s car—the blue-and-white Toyota—that belonged to their father—but Josephine declines politely and says, ‘It’s so close, I can walk there.’

‘Then let me walk with you,’ he pleads.

‘I have to walk really fast …’

‘Ah, I’ll try not to slow you down then.’

~~~

The scorching sun is perched high in the sky, and the wind is howling when they walk out of the house together. They take the route that cuts through the old police barracks and both of them walk in silence, their heads bowed as if in shame. Their steps match as if rehearsed, and soon enough they are on the road that cuts through the unfinished hospital building. Nikesh is absorbed in memory so he does not observe Josephine’s face when she tells him, ‘The last person he asked for before he died was you.’

‘Me?’ he asks distractedly, and turns to face her.

‘Yes, you. After all these years, you are all that occupied his mind,’ she says.

The bitterness in her voice makes the sun feel hotter against the nape of his neck, and he takes one long stride, putting him before her, as if he wants to get away from her.

‘He is dead now, Josephine,’ he turns to look at her and says, ‘It doesn’t matter anymore.’

‘But it does. I was his wife. I stayed with him all these years.’ Her voice sounds as if it is about to break, but she says, ‘You wrecked him.’

‘Josephine, we were young. You can’t hold that against us—against me—forever.’

‘When your father … when he made me promise never to tell anyone else what I had seen, I thought I would go insane with that secret … I thought I would burst from it or it would eat away at my insides, but I kept it. I never even told your mother.’

‘You found us and we begged you not to tell anyone but you told my father, why?’

‘It had to stop. That madness had to end.’

‘And he sent me to India. A place I had never been to in my life. Somewhere I knew no one. I loved Sam, and it turned out to be a curse.’

‘If you loved him so much, why didn’t you try to reach him after your father died? You could have asked Tara for his number …’

‘I was scared.’

‘Of your dead father?’

‘Of him … of Sam. I didn’t know if he still remembered me.’

‘You are all he talked about.’

There is silence between them as two old women dressed in marching kitenge dresses walk past them. The silence persists long after the women have disappeared.

‘Tell me, Josephine, why did you marry him even though you knew?’ he asks, turning to face her. When she does not respond, he asks again, the anger and impatience in his voice reminds him of all the times his wife has told him that he could burn the world with his hot temper. He breathes through his mouth and counts from ten backwards just as the therapist instructed him. His head spins and the world around him spins with it.

‘Your father made me. He doubled my salary, paid for my mother’s treatment when she had tuberculosis until the day she died, and he told me he didn’t want Sam to get lost since he considered him a son.’

‘My father?’

The wind blows against his face and a few metres away, a whirlwind rises and churns, carrying with it dust and plastic and broken things—like forgotten love and everything else that is lost and has ceased to matter. It spins on the ground, past a rock, to a grass patch and then it dies down.

If you cover a kalausi with a basin, you will find a snake underneath. He thinks back to Sam’s voice telling him that the day he taught him the Luo word for whirlwind, teaching him that if one suppressed something as strong as an emotion, they would end up with something venomous and spiteful. He remembers struggling to pronounce the word, and Sam laughing at him. He can see clearly the happiness on Sam’s face that day. He wonders if there were any traces in Sam’s face after he left.

‘Tell me Josephine, did you love him at least?’

~~~

At the morgue, the tall and dark security guard with the voice of a bullfrog tells Nikesh that he cannot go inside, and he has to wait under the tree towards the gate since he is not a family member. Josephine pauses at the door and looks back at him as if to say, I have won this time.

Nikesh watches her disappear into the mouth of the dark hall. He waits until he can no longer see her back before taking five long strides towards the entrance; he hands the attendant a crisp one-thousand-shilling note and walks in a few paces behind her. He notices her startled face crunch up and her mouth twists with what he knows is disgust but he tells himself that, in fact, he has won—a more significant win.

Sam’s body, naked and partly covered with a moss-coloured sheet, lies on the concrete slab. It looks like life left it ages ago, and he wonders if Sam really died of coronary heart disease —after all, he was still too young for that—or of a heartbreak left to fester for too long. He instantly has a premonition of what will kill him too. He stands beside Josephine, and both of them look over Sam’s lifeless body. They say nothing to each other, silent as if only now realising the gravity of Sam’s death, as if only now realising that this is no longer a game.

They stay that way until the guard comes in and tells them their visiting time is up. Nikesh pulls him to the side and asks for a bit of time with the body—alone. He watches the attendant escort Josephine out of the building, and something about the way she limps while swaying with grief fills him with an unbearable kind of sadness, he feels as if he has taken everything from her. Even now.

Left alone with Sam, he runs his index finger on his hairless torso, resting his palm on the ashen bulging chest. It is no longer as warm like it was when they were young and were sneaking around at any opportunity they got in the back of his father’s shop. He thinks back to everything—the love, the sex, the separation, especially the separation.

‘Sam, why did it have to turn out this way?’

Apart from the continuous, prolonged humming of the mortuary freezer, the whole place is silent, and he feels stupid for wanting a response from a dead body. He now feels foolish for having flown all the way, having left his wife and children just to see a dead man. His lower lip starts to tremble and his teeth chatter and the muscles of his legs become taut. Afraid that he might topple and fall over, he props himself on the slab and curses vehemently. Spittle jumps out of his open mouth and lands on Sam’s body. Nikesh closes his eyes and breathes while counting back from ten to one. He counts over and over again until he can no longer hear anything but his own voice. After a few minutes, he feels he is back to himself, and he uses the sheet to wipe the spit off while apologising for being such a wreck. He kisses Sam on the forehead, his lips leaving a smudge of saliva on the skin. He says goodbye.

Briskly, he walks out of the morgue and finds Josephine waiting by the door, her arms wrapped around her as if to ward off the sadness, and her round, unattractive face openly brimming with sorrow and anguish. He stretches his arm towards her to hug her, but she has her arms crossed over her breasts, poking his chest when he leans in further. He pulls out from the awkwardness of the hug, stares into her large, motionless eyes and tells her, ‘I’m sorry.’

He does not wait for her to say anything back to him. With tears in his eyes, he walks away, through the gate about to fall off its hinges and down the dusty road with a puddle of brown water in the middle. He turns right at the junction. He takes the route that leads him away from the morgue, away from his parents’ home—he cannot face Tara with what he feels is her silent condemnation of his decision to stay away from their parents’ funeral and his refusal to have their ashes sent to him—past the playground where there are no children running after a ball, beyond the rows of shops with walls eaten away by time, all the way to where it all began; the back of his father’s shop. Once there, he sits down at the steps of the small door that leads to the loading zone. Only now does he allow the memories to come. As water bursts from the broken wall of the dam, they push through.

~~~

It begins with their first meeting, that afternoon when his father walked in with a lacklustre-looking, scrawny boy with uncombed hair into the shop and told them that he would be the new loading boy.

‘Nikesh, this is Sam,’ his father said as he pointed to the boy who appeared timid and shy.

The boy’s eyes gleamed as if they were the only things in the entire world that belonged to him; the only thing that he could claim with pride. Nikesh repeated the name in his head, and although it was such a simple, ordinary name, the taste it left on the tip of his tongue as he turned it in his mouth felt like something sweet that one never wants to finish.

In the days that followed Sam’s arrival at the shop, Nikesh watched him with the curiosity of a child who had found a new pet or a plaything. Slowly, as more days passed, the curiosity morphed into something else, a newfound friendship that had them glance and smile at each other with an understanding that escaped words altogether. He started moving closer to Sam, handing him a bottle of water when he saw him dripping with sweat, helping him offload the bags of rice or flour when he saw him struggling with the weight.

One day, his father saw him help Sam with the loading and unloading and called him, ‘Nikesh, come here. You need to learn what goes on in front of the shop instead of what goes on at the back. That is the foreman’s job.’

‘Baba, I was just helping,’ he said, grumbling.

‘You don’t help those people with the work I pay them to do.’

He turned to look at Sam who was at the door with cartons of powdered milk, coffee and spices hauled over his shoulder, his head tilted to the right by the strain of the load on his neck, and sweat dripping down his bare torso. In that moment, seeing the tar-black smooth skin and the taut muscles Nikesh struggled to fit Sam in the words ‘those people’ but failed, and he walked away from his father, towards the boy to help him offload the brown boxes and put them on the floor. His desire had welled him up with the impulse for defiance, filled him with the spirit of rebellion. The boy’s whisper to thank him, simple as it sounded then, forever stayed in his memory as if he handed him a lifeline.

‘Baba, he is just a boy like me. I bet we are the same age,’ he said when his father questioned his defiance. He shoved a spoonful of curry in his mouth, letting the chilli burn his palate.

‘Maybe that means you should be working as hard as him.’

‘It is child labour.’

‘You are sixteen, Nikesh. Not a child.’

‘Still …’

‘He needs a job. He told me he has no parents, said they died when he was still a child, and he needs money. Am I a monster for wanting to help him? Huh, Nikesh, should I have turned him away?’

‘Nikesh, listen to your father and finish your food.’ His mother’s voice cutting him before he could respond to his father and the sigh afterwards, ‘Why can’t you be like Tara who never argues?’

~~~

He remembers that conversation like it is happening while he is sitting on the steps of the shop. He gets up and checks under the stone where his father always kept the spare key. He knows Tara no longer operates the shop so he does not think the key will be there when he flips the rock over. He finds it, rust clinging to bow and shaft, and a fat pink earthworm crawls on top. He nudges the worm away, and picks up the key. He opens the door to the dark part of the back of the shop.

Once inside, he finds himself thinking back to how it happened the first time, and everything that followed. He allows himself to peel away the memories even though it is layers and layers of pain beneath. He recalls the feeling of completeness that came with being around Sam, of being so close their skin might as well have merged into one, the intensity of the kisses that left them yearning for more. Like an unwanted part of a song that you skip over, he rushes past the memory of the loud gasp from Josephine’s lips that day when she found them—Nikesh bent forwards, holding onto the cartons of Omo. He forces himself to remember the pleading, begging, and promises if only she did not tell his father.

Three days passed, that is how he remembers it now, and he thought she had been kind to him and not told anyone. The fear receded, and he stopped wondering when his father would rain brimstone on him. The fourth day comes back to him clearly because that was the day his father informed him that Sam was unwell and would not come to work. Back then, he saw nothing unusual in that.

On the fifth day, he overheard his father telling his mother, ‘That boy is becoming something else. We can’t continue having him here.’

The sixth day: ‘I have spoken to your Aunt Visha in Mumbai, and she has found you a good school near where she stays. You leave in three days.’

No room for negotiations.

Everything suddenly became a whirlwind before his eyes. Three days were not enough for goodbyes. Furthermore, his father forbade him from seeing Sam.

However, the memory that persists, the one that Nikesh chooses to hold close, is the one in which he sneaked out of the house one evening when his parents were not around. He walked all the way to the dimly lit single room Sam shared with two other workers. They lay in silence close to each other on the single bed with a razor-thin mattress, the contrast in their skin colour like two distinct worlds.

Sam turned to him, looked at him with eyes the colour of brown marbles and said, ‘Niki. My Niki, I like you so much. You know? But your father …’

Nikesh pushed his tongue into Sam’s mouth, interrupting the flow of words, and pinned him against the wall until their breathing merged into one, and they both ran out of breath. He wanted to let go but he could not, and his fingers groped Sam’s body. His palm pressed on Sam’s erection, rubbing it gently, and he gasped with pleasure, and the strange warm bubbles of air escaped from Sam’s throat into Nikesh’s mouth who said, ‘My father is sending me to India. I leave tomorrow morning.’

He does not remember Sam’s body tightening with that revelation. He does not remember both their eyes roaming in the low light, searching, seeking, wanting. He remembers the silence.

~~~

- Troy Onyango is a writer from Kisumu, Kenya. His work has been published in Prairie Schooner, Doek!, Wasafiri, Isele Magazine, The Johannesburg Review of Books, AFREADA, Nairobi Noir, Dgëku Magazine, Caine Prize Anthology (Redemption Song & Other Stories), and Transition, among others. The winner of the inaugural Nyanza Literary Festival Prize and first runner-up in the Black Letter Media Competition, he has also been shortlisted for the Caine Prize, the Short Story Day Africa Prize, the Brittle Paper Awards, the Miles Morland Foundation Writing Scholarship, and nominated for the Pushcart Prize. He is the founder and editor-in-chief of Lolwe.

~~~

Publisher information

Troy Onyango’s For What Are Butterflies Without Their Wings is a collection of twelve short stories that have a quickening pulse and pages crackling with sharp observations and gentle revelations about solitude, loneliness, connection, loss, love, and the infinite intricacies of daily human life.