The JRB presents an excerpt, in isiXhosa and English, from DDT Jabavu’s travelogue In India and East Africa / E-Indiya nase East Africa.

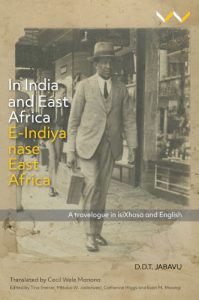

In India and East Africa / E-Indiya nase East Africa: A Travelogue in isiXhosa and English

Written by Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, translated by Cecil Wele Manona, and edited by Catherine Higgs, Evan M Mwangi, Mhlobo W Jadezweni, Tina Steiner

Wits Press, 2020

In November 1949 DDT Jabavu, South African politician and professor of African languages at Fort Hare University, set out on a four-month trip to attend the World Pacifist Meeting in India. Jabavu wrote an isiXhosa account of his journey, which was published in 1951 by Lovedale Press. This new edition republishes the travelogue in the original isiXhosa, with an English translation by the late anthropologist Cecil Wele Manona.

Read the excerpt, in isiXhosa and then English:

~~~

Ukutya kwasenqanaweni

Abelungu bathi inqanawa le yihotele edada emanzini, batsho benyanisile kuba ukutya kwasenqanaweni yeyona nto ilungele umntu ofuna iholide ephilisayo kumzimba odiniweyo, ngokukodwa kwaFirst Class, kanti nabakwaChisana (Third Class) bayalungelwa. Umntu ma kakhe azilingele akhwele eMonti aye eKapa, ayibone into yamehlo. Apha ke okoko sandulukayo eThekwini sivuswa kwakusasa ngo-6 ngekofu ehamba nekeki nama-apile. Kulandele iBreakfast ngo-8:30 ngothotho lwezi zinto: iziqhamo ezikhutshwa emkhenkceni sele zihlinziwe: ivatala, iphopho, puffed rice, corn flakes, oatmeal, intlanzi erhoqwe neetapile eziqhinwe ngamafutha, Broiled Bacon and eggs, Toast scones, rolls, marmalade, coffee, cocoa, tea, ubize ngokuthanda; phandle ngentlazane ice-creams; emini emaqanda yiLunch: soup, eggs, curry and rice, steak and onions, Oxford bran, roast lamb, vegetables, jam tart and sauce, cheese, biscuits, coffee, fruit. Lakujika igala emveni kokuba besilele ubuthongo ikhenkceze intsimbi ebizela kwitea enohlantlalala lweekeki, baye abanye bezongeza ngobhelu lomsele enkantini ekwalapha, bambanguze. Ngo-6 ibethe intsimbi yokuba siye ezibhafini ezithulula iziphango phezu kwentloko (sibe ke sivukele kuzo nakusasa) ukulungiselela idinala 7:30 ngokuhlwa emasiyihombele ngemithika emnyama neengaga ezimhlophe nookrukrindlathi, sifane noojobela namahlungulu, idinala engaphezulu kunaleya yasemini ngobuninzi bokutya, ibe isekho isopholo elandela umdlalo weBioscope. Nguloo mgidi ke le mihla, into etsho umntu aphume emhle elithengethenge ukutyeba mhla wehla enqanaweni ngokukodwa xa evela ezweni elibalele ilanga eyothuka indyebo engumdliva ongaka, kuba abelungu bona abothuki nto kule ndyebo noko benqinile. Thina sisuke sibe zizambuntsutsu, kube nzima nokuphakama etafileni. Into yona endivusela umona yinja yomlungukazi othile ongumhambi kunye nathi, etyiswa ngokolu didi lwethu. Bafondini! Ihlutha ibe likiyokiyo imbinambineke nokuhamba, ndive ndicinga izilambi zakowethu. Phaya ngasekhitshini leThird Class ndibone kukhulekwe ibhokhwe enetakane. YeyamaMoslem la aya eIndiya, kuba isiko lawo kukutya inyama azixheleleyo ngokwawo.

Le nto ucingo yinto, kuba ndifikelwe lucingo lomoya (wireless) olubethwe ngezolo eLondon yintombi yam enkulu indinqwenelela uhambo oluhle. Luze ngendlela ethi, ‘Marconigram from ship to ship’ ukunduluka eLondon, ludlule eKapa kunikelwana ngalo ziinqanawa, lwaza kugaxeleka kule, kuba zona ziyazana. Injalo imfundo yamagwangqa.

Mombasa

Ngoku sigqithele eMombasa idolophu (100 000) enganeno kancinci kwiBhayi (150 000). Intle isimanga ngenxa yemithi emide (60 feet) ethe shinyi imithi yeCocoanut, neeMango, neeCachoanuts, neebhanana, nesundu, nemibaba, ekhumbuza iPort St. Johns emaMpondweni. Mininzi imithi yeBaobab, imixanduva yona. Omnye ndiwujikelezile ndawufumana ungama-20 eeyadi wanganeno kakhulu kulowa ndawubona eTransvaal (Louis Trichardt) ngokuya ndandisemjikelweni (1947) wekomiti karhulumente yokuphicotha izivukavuka zeesinala; wona wawudlule kwi-150 unokwanela ukugqojozwa uhambe inqwelo neenkabi zayo njengaseCalifornia (USA). ETransvaal imbalwa, yimingqandende apha naphaya. EMombasa yintlaninge engenakho ukubalwa, kuba isezweni lobushushu ethanda bona ibe iMombasa ikufuphi neEquator (300 miles) yayamene neAbyssinia neJiphethe nelabaGanda nelamaSomalia. Kaloku amaSomalia ngawo ekuphunywa kuwo ziintlanga zamaLawu, namaNamaqua, namaDamara, namaHerero, esiphithikezwe ngawo sikhanya nje thina boMzantsi, kuba bakhweza iKhongo behla ngonxweme lwaseNtshonalanga emfudukweni (migration) yabo yafamlibe baza kuwa eNamaqualand bathi saa ukuya ngaseKimberley naseKokstad naseGeorge naseBhofolo naseMpofu naseXesi nasemaMpondweni baxubana nathi. He!

Isikhephe sime iintsuku zontathu eMombasa ndaza ndaxhamla iimbeko ezinkulu ngenxa yokuba lihlakani likaManilal Gandhi kuba le dolophu ikholise (90 per cent) ukuba yeyamaIndiya kobo bungako bayo xa siyithelekisa nezi sivela kuzo: Zanzibar (50 000), Dar es Salaam (60 000), Mozambique (9 000), Beira (13 000) neLourenço Marques (70 000). Siqale samenyelwa kwimbutho esebhomeni (garden party) lomzi wesityebi esiphambili seIndiya ukuze siwise iintetho kumanyano lwawo. Zalapho zonke izinonophu zawo: amagqirha, amagqwetha, neentloko zamashishini. Ngosuku olulandelayo simenyelwe ezidinaleni neesopholo kumakhaya ngamakhaya azo, amazulwana emhlabeni atsho koyikeke nokungena ngenxa yenkazimlo yezibane zeletrikhi eludongeni kwa usangena ngesango leemoto, kunge ziinkwenkwezi entungo, nobuhofohofo bezitulo, nobutofotofo beekhaphethi phantsi. Bafondini buyatyiwa ubukumkani ngabanye abantu! Abasalikhathalele izulu eli silinqwenelayo emva kokufa. Nam ndiphantse ndaphelelwa libhongo. Omnye wabo undisube ngomhalatushe wemoto yakhe imini yonke wandihambisa endibonisa imizi eyakhiwe sisiPalato (Municipality) ukuhlalisa abaNtsundu abaqeshiweyo, neholo entsha yeentlanganiso, nezikolo, nemarike, nemikhalambela yezindlu zezikhulu zamaIndiya neehotele eziqeshwe kuwo ngamaNgesi, adlulela emaphandleni apho kuhlala amaAfrika, amaSwahili, namaNyamwezi apho kufuywe iinkomo ezimalunda neembuzi. Ngokuhlwa sibonele ibhayaskophu silihlokondiba lamadoda neentsapho zawo.

Izindlu ezakhelwe abaNtsundu kwidolophu le zintle ngokwezaseMacNamee Village eBhayi, kodwa inkankane isekubeni ayisoze ibe yeyakho indlu; umniniyo yidolophu; phuma wena mhla waluphala, ushenxele osemtsha, ugodukele emaXhoseni. Yinqojela ke leyo. Ziphele iintsuku zethu eMombasa siyolelwe ngenyani, sabuyela kwiKaranja ethe apha yakhwelisa inyambalala yabantu ekubaluleke kubo uhlanga lwamaIndiya olungamaShiki (Sheiks Sikhs) oludume ngamandla ezigalo nokhalipho ezimfazweni. Bonke bade, yimiximondulo empantsha iiqhiya ezinkulu ezimhlophe, engachebiyo, ebuso busisamfumfu ziindevu, amaxhonti.

NgeCawa 20 kweyeNkanga 1949 sibe namangcwaba amabini: usana olunyanga zilishumi olufe lihlaba (pneumonia), nexhego (70) laseKapa ebe lifuna ukuya kufela ekhaya sisifo sentliziyo. Akubanga kho nkonzo nasaziso sani. Izidumbu zithandelwe ngeseyile zathungelwa kuyo ngokomqwayito wehagu kushiywa iimfingwane mancamini omabini, kwabotshelelwa iintsimbi ezinkulu zobunzima zokwenza zizike, zajulelwa elwandle ingemanga nenqanawa, ayibi nto yakoonto loo nto, kangangokuba uninzi lwabantu alwazanga nokuba kufe mntu. Nam ndiyive ngencoko yegqirha lenqanawa endihlala kunye nalo etafileni, ndaqonda ukuba le nto ukufa ayisenavuso kwezi mini.

Ngenye imini ndibe nethamsanqa lokumenywa ngumphathi (Commander) ukuba ndinyuke naye ndivelele iqonga lakhe (bridge) phezulu encotsheni apho lubonakala lonke ulwandle nendlela esiya kuyo. Undibonise apha yonke intsimbi ebubuchopho obulawula inkqubo yokuhamba. Alapha amajelo abonisa indawo esikuyo elwandle, namaqhagana ekucinezelwa wona ukuvala iintoyinto nokulawula into emayenzeke. Kumhla ndiyibonayo le ndawo. Ilapha indlu yakhe yokutya, nokulala, nokubala, nokubutha—ubunewunewu neemfamfam zodwa, khwetha. Yinkinga le, umfo onesithozela, iNgesi lohlobo ebendingazi ukuba lusekho, ngobubele. Ndithe yinto ukunonelelwa ngongaka. Kudala ndizikhwela izikhephe, kodwa intsha le into yokukrotyiswa ingcwele ngumniniyo. Phofu namanye amaNgesi ongameleyo enqanaweni apha kundawo zawo ndiwafumene enje ukuba nobuntu. Ayikho kuwo ingqondo yokurhanela umntu oNtsundu okokuba uyingozi. Naphaya eMombasa ndifumene amaNgesi enikele oololiwe kumaAfrika kwa kubaqhubi beeinjini de kube kwiigadi nooNomatikiti, nabashanti abangawuhombele nganto lo msebenzi wabo; owofika behamba ngeenyawo, bengenaminqwazi, benxibe iihentshana zangaphantsi (vests) zodwa bebetha imilozi namakhwelo bonwabile oonkabi ngokwasemaXhoseni.

Esi sikhephe side sazala ngoku ngabantu oko bengena bengenile kula mazibuko. Ngathi bangayilingana idolophana engangeKhobonqaba, kuba thina bahambi sili-1 400 ngaphandle kwabaqeshwa abakwasewakeni nabo. Thina baNtsundu kwiFirst Class singaphezulu kubelungu ngenani, into leyo endonwabisileyo ukuba sesinyakanyakeni sabantu endaweni yokuba ndibe mphoko njengakwinqanawa zecala leKapa-England apho ndasoloko ndingumtshonyane osethafeni nekheswa phakathi kwabelungu. Kuxinene kwaSecond Class nakwaThird, kanti abona bantu baninzi ngabakhwele phandle (deck passengers) ebandezini lelanga eliyionti, nasezimvuleni, kumgando wengxinano eyoyikekayo bengenayo nendawo yokuhambahamba, kuphela kukuhlala nokungqengqa nokuma ubomi abakubo. Bahleli phakathi kwemifufulo yempahla yabo esezingxoweni neebhokisi; ilapha imibhalo yokulala, zilapha iibhayisekile, zilapha izitovu zabo zokupheka kuba batya ngokuzibonela, bahlambele kwalapha; kanti obona bubi busekuseni ngo-4 xa oomatiloshe behlamba inqanawa yonke ngemibhobhokazi emikhulu yamanzi atsalwa elwandle, kube yimikhwazo engapheliyo ukuvuswa kwabo ngetshoba, kulumeze ukugalelwa kwaloo manzi ngobubhukru obungenanceba kukhala abantwana, ube ngumbhodamo wengxovu le mihla.

Ukuchitha isithukuthezi oko ndakhwelayo ndizenzele isiko lokubetha ipiyano iyure yonke kusasa, kanti ndiyazinceda ukolula iminwe eseyaqothola, nokuvuselela iingoma namaculo ebesele elele izigcawu entloko, kuba okoko ndaphulaphula ukubethelwa ngabantwana bam ndayityeshela into yokuzibethela, njengoko ndandisenza ngowe-1921 ndisaphethe iFort Hare Choir. Kaloku ndandigqadaza ngoko ndinganqene ndoda kwiMusic. Apha ke ndizivuthulule uthuli yada yanokuvakala into endiyibethayo nakubaphulaphuli. NgoMvulo 21 kweyeNkanga 1949 sigqibe iimayile ezili-1 012 ukusuka eMombasa semisa kwiziqithi ezininzi kakhulu zaseSeychelles ezingathi ngamatye amakhulu athe thu emanzini, koyikeke xa inqanawa ipotapota ukufuna indlela phakathi kwawo. Kuluhlaza apha ziimvula ekubonakala ukuba ziluncedo kwabaphila ziziqhamo; sibone kulayishwa iiPineapple ezisimanga ubukhulu, saza ekudluleni sayishiya ngasekhohlo iCape Guardafni eyincam yeAfrika nekungenwa ngayo eGulf of Aden kulwandle oluBomvu (endandiluwele entla 1928). Ngoku sicanda iArabian Sea entla kweeMaldive neLaccadive Islands. Onke la magama ayaziwa yimpi yeRoyal Readers. Sinyuke, sanyuka, sawuwela umda weEquator, sada salibona izwe laseIndiya 26 kweyeNkanga 1949 kwizibuko ekuthiwa yiGoa (Marmugao) elisaphethwe ngamaPhuthukezi. Sime imini yonke apha (ngoMgqibelo) sayijikeleza idolophu, sibuka izindlu ezakhiwa ngamabandla kaVasco da Gama kudala, sihamba phantsi kwemithi emide yeekhokhonathi, ndaba ndiyaqala ukulinyathela elamaIndiya, sesisondele eBombay ngekhulu elivayo leemayile.

Bombay

Sihambe usuku lwalunye, kwasa singena eBombay ngeCawa 27/11/49. Le nqanawa ngokwesiko ikhawulelwe kwakude ligosa (Pilot) lokuyikhokela nokuyingenisa echwebeni, ekuqheleke ukuba libe ngumlungu, kodwa namhla yaliIndiya, saba sigqibelisile ukubona umntu omhlophe emagunyeni naphaya ezibukweni kubahloli beempahla (customs officers) nabeencwadi zemvume (immigration passports) safika ingabantu abanobubele ezindwendweni, apho thina siqhele amagadalala afinge iintshiyi ngenxa yokucaphukela umXhosa naxa engonanga nto. Ndonwaba ke namhla ngesi sizathu kulo lonke uhambo lwam eIndiya apho ilizwe lilawulwa ngabaninilo.

Elwandle le dolophu iBombay iqala ithi thu ngesangcunge sesakhiwo samatye esilisango elibanzi elilelona lokungenisa umntu eIndiya (Gateway of India) ngokukodwa izinqununu zoburhulumente neekumkani zamaNgesi ngokuya ayesaphethe. Lo ngumbono otsalayo kumfiki kuba ucaca kwa kumgama omde. Ekufikeni sidluliswe kamsinyane ngabahloli safika sesihlangatyeziwe yikomiti, sakhawulelwa ngemincili kwa sisehla, yasigangxa entanyeni ngeentambo ezintle (garlands) eziphothwe ngeentyatyambo ezibomvu saya kukhweliswa kwizivetyuma zeemoto zezikhulu saba siya yisungula loo dolophu inkulu (5 000 000) ekuthiwa ilandela iCalcutta neLondon ngobukhulu kwezasemaNgesini. Ukuze umfundi abunakane ubukhulu bayo mandithi abafundi bayo abaphumelela iMatriculation ngonyaka omnye ngama-62 000. Qonda ukuba eKapa mnye uloliwe ngemini ophuma acande izwe elingangokuya eRhodesia (Main Line Train), kodwa eBombay ngama-21 ngemini iitreni zolo didi zibe ezisekhaya (Local) zikuma-300.

Imibono ngemibono

Siyityhutyhile le dolophu ngesitalato esikhulu sesazulu sayo iMahatma Gandhi Road, igama eliguqulwe bumini kwelangaphambili lesiNgesi, umtyululu ophahlwe yimihohoma yamabhotwe abukekayo, ekuthe silapho seemandla ibala elikhulu, ithafa lokudlalela ikrikethi, isixaxabesha esiginya abantu abakuma-200 000 elona bala likhulu lemidlalo kuyo yonke iAsia. Ewe nakubeni bekuyiCawa sibone inyakanyaka yabadlali abavethe ezimaweza, bedlala nkqi, ibethwa ibhola iye kuwa ele komda ziinkintsela zeendlali ezindikhumbuze inzwana yakudala engasekhoyo uRanjitsinji endandiqhele ukumbona (1905) eNgilani ndisalidlala iqakamba ndingumfana.

Kaloku eIndiya umhla weCawa yinto yamaKrestu odwa; abona bantu baninzi banqula uBuddha, noMahomete, noConfucius, noKrishna, noLaotse, nezinye iingcwele eziqalisela kude phambi kwexesha likaYesu benezabo iintsuku zokuthandaza evekini le. Ngoko ke imisebenzi yorhwebo, nemidlalo, noololiwe, neenkundla zamatyala, nokwakhiwa kwezindlu, nolimo, zonke izinto azinamini yakuma. Izitalato noko zibanzi zixinene ngokoyikekayo ziintlobo zonke zeenqwelo: ootram, izikhotshi ezitsalwa ziinkabi zeenyathi (kuba bendiqala ukuyibona inyathi, ingxukuma mfondini engangeenkabi ezimbini iyodwa) neeriksha zabantu ezifana nezaseNatal koko endaweni yokutsalwa ngumntu zirhuqwa ngebhayisikili; namagemfana (gigs) ehashe elinye, neekhebhu zamahashe zohlobo lwakudala (1913) olwagqityelwa mzuzu (1923) eKapa, neendidi zonke zeemoto, zaye zibalekiswa ngohlobo olulumezayo kuloo ngxinano yeenkomo ezisengwayo, neebhokhwe ezingaluswayo, namathole anqumla naphi na naninina. Sisimanga esi kuba akukho nto igilwayo. Umqhubi uyigibisela njalo imoto, evuthela ixilongo po-po-po-po ephephaphepha le nto naleya kodwa enganyatheli nto; kuqhuba namaxhego anezimvi antshebe zimhlophe ohlanga lwamaSiki (Sikhs), amarhasha wona ampantsha iidukhwe ezingathi zizidlokolo.

Amahashi wona andidanisile, kuba asuke ayimigqutsubana noko etsaliswa imithwalo emikhulu.

Ilanga

Ilanga laseBombay litsho ndadamba igugu; sisifuthufuthu esingathi kuvulwe isiciko selaa ziko likaNebukadenetsare ethafeni leDure, isivuthevuthe esikwenza ubile ube lichebencu uhleli emthunzini, ubone ngamaluluwe elandelelana. Ngenxa yesi sizathu ndibone kusasa nje umlingane wam uManilal Gandhi, xa sinxibela ukuyishiya inqanawa, ezifumbelela etyesini zonke izinxibo zakhe zesiNgesi abekade esebenzisa zona, efaka ezimaweza zodwa, imithika emhlophe, iifaskoti zekeleko, nemibhinqo emifutshane yesiIndiya ebizwa ngokuthi yi ‘doti’ into ebulokhwe-bhulukhwe emilenze ivuliweyo ngemva ukungenisa umoya ezintungweni. Ndive ndinqwenela xa ezam iibhatyi zobusika neendulubhatyi zazo neekhala neebhulukhwe ezibutsotsi zitshisa oku kwesitovu!

Ikomiti isabele ukuba sifikele kumzi wegqirha elihlala kwiopstezi yesihlanu, kubantu abanobubele abasinqake kwangoko ngeziselo ezibandayo, kwayintswahla yencoko engezinto zonke, ikakhulu ngeAfrika.

~~~

Food on the ship

Whites say a ship is a hotel that floats in the sea. That is true because the food suits one who wants to rest, especially in first class, though the position is not bad even in third class. Try and test this by travelling by sea from East London to Cape Town. Since we left our country, we are woken up at 6 a.m. with coffee, cake and apples. Breakfast is at 8:30 a.m. and comprises several items: fruit from the ice chests, watermelon, paw paw, puffed rice, cornflakes, oatmeal, fish with chips, broiled bacon and eggs, toast, scones, rolls, marmalade, coffee, cocoa, tea, and you can eat as much as you like. Outside in the morning they serve ice cream. There is lunch at noon: soup, eggs, curry and rice, steak and onions, Oxford bran, roast lamb, vegetables, jam and sauce, cheese, biscuits, coffee, fruit. In the afternoon, a bell is rung and reminds us to get cakes, while some drink in the bars and get drunk. At 6 p.m. a bell reminds us to go and shower (we shower in the morning as well) to get ready for supper at 7:30 p.m., where we wear dinner attire. The food in the evening is more plentiful than the food served at noon, and after the film show there is food again. We feast like this every day, something that leads one to become very fat until disembarking, especially if one is from a country which does not have plenty. But whites are used to these big meals and remain thin. We eat too much and it is a struggle to get up from the table. But I was annoyed to see a white woman feeding her dog with the same food we were eating. Folks! This dog eats so much it cannot walk. This made me think of the many poor people in my country. Near the kitchen of the third class, I saw a goat tied up and it had a kid. It belongs to the Muslims travelling to India because according to their custom they must eat meat they have slaughtered themselves.

Communications are important. I received a telegram sent by wireless by my daughter in London, wishing me a safe journey. It came by ‘Marconigram from ship to ship’ from London via Cape Town, and it was passed on from ship to ship. That is how the education of white people is.

Mombasa

We arrived in Mombasa, a city with 100 000 people, which is slightly smaller than Port Elizabeth (150 000). It is very beautiful because of its tall trees (about 60 feet), such as coconut, mango, cacaonuts, bananas, palm trees, which remind one of Port St. Johns in Pondoland. There are many baobab trees which are very big. One was 20 yards in circumference, and was smaller than the one I saw in the Transvaal in Louis Trichardt when I was there on a tour in 1947 with a commission which was investigating college unrest. That one is so big that an ox span could pass through it, like in California in the United States of America. These trees are few in the Transvaal whilst in Mombasa they are frequent, because of the humid warm climate—this city is near the equator (300 miles). Mombasa is close to Abyssinia, Egypt, Uganda and Somalia. The Somali are the origin of the Khoi, Namaqua, Damara and Herero who introduced the lighter complexion to us in the south, because they moved along the Congo down the western coast in their migration long ago to Namaqualand, and spread out to Kimberley, Kokstad, George, Fort Beaufort and Balfour, Middledrift and Pondoland where they mixed with us. He!

The ship stopped for three days in Mombasa and I was honoured in being with Manilal Gandhi, because 90 per cent of the inhabitants of this town are Indians compared to the towns we had already passed whose Indian population stood at: Zanzibar 50 000, Dar es Salaam 60 000, Mozambique 9 000, Beira 13 000 and Lourenço Marques 70 000. We were first invited to a garden party at the home of a rich Indian and we had to say a few words to their association. Dignitaries there included doctors, lawyers and leading businessmen. On the following day, we were invited to lunch and dinner at various homes, and these were like small heavens on earth that made you fear to enter because of the electric lights on the walls, the comfortable seats and the thick carpets. Good people! Some people are enjoying the kingdom, they do not care for in the hereafter which we desire. One of them took me by car and showed me the municipal residential area where blacks live, a new community hall, schools, markets, big Indian houses and hotels which are leased from them by the English. We also went to the countryside where we saw Africans who are Swahili and Nyamwezi. They rear oxen with humps on the neck and keep sheep. In the evening, our hosts showed us a film and we spent time together with their families.

The houses which have been built for blacks here are as good as those for blacks at MacNamee Village in Port Elizabeth, but the trouble is that they can never own the houses, they belong to the municipality. You must leave once you become old, give way to a younger person and go to the country. That poses a great problem. At the end of our stay there we were very happy and returned to the Karanja, and many people joined us. Among them were Indian Sikhs, who are well known for their bravery and the wars they have fought. They are tall, strong and wear large white headgear. They do not cut their hair and have long beards. On Sunday, 20 November 1949 we had two funerals: one of a 10-month-old baby who had died of pneumonia and of a 70-year-old man from Cape Town, who had wanted to die at home because he had a heart disease. There was no service of any sort. The bodies were wrapped in a sail into which heavy iron bars were placed and then they were thrown into the sea without the ship stopping. And that was that. Some people did not even note that there were people who had died. I got to know about it from a doctor who shares a table with me and I realised that people these days take death with ease.

One day I was fortunate to be invited by the Commander of the ship to visit his platform so that we could see the sea and where we were going. He showed me how the ship is steered. There are instruments which show where we are and many other gadgets. I saw his dining room, bedroom, office and resting room. This is a great man, he is dignified, one of those kind Englishmen who are now rare. I felt greatly honoured. I have boarded many ships but this is the first time that I am entertained by the Commander himself. Those are the people who do not treat a black man with suspicion. Even in Mombasa I noted that the English had employed blacks as train drivers, firemen, ticket officers and shunters. They walk barefooted, do not wear hats, they wear only vests, whistle and are as happy as the Xhosa at home.

There were more and more people who boarded the ship as we moved on. The people on the ship may number as many as the inhabitants of Bedford because there are 1 400 passengers and about 1 000 crewmen. There are more blacks in first class than whites and this pleased me, because on the Cape Town–England route I have always been the only black on each ship. Second and third classes are by now very crowded and most passengers are deck passengers who are exposed to the hot sun and the rain, and they are fearfully crowded because they can only stand or lie down. They sit in the midst of their baggage, beds, bicycles and stoves because they must cook for themselves. They wash here too. And you must see how bad their situation is in the morning. At 4 a.m. the ship must be cleaned and water from the sea is sucked and pumped onto the deck. This causes such commotion and makes the children cry.

To while away my time, I made it a point to play the piano for an hour in the morning and this helped my fingers to remember the songs I had forgotten. My music became stale when my children began to play the piano for me at home. Yet in 1921 I was playing the piano regularly when I was in charge of the Fort Hare Choir. I was active then and I feared no one in music. The passengers appreciated my music on the ship. On Monday 21 November 1949, we completed 1 012 miles from Mombasa and stopped at several islands of the Seychelles which look like large stones in the sea. You would be amazed to see the ship steering its way through those islands. The islands are green and people live on fruit, and very large pineapples were loaded onto the ship. As we went on, we passed Cape Guardafni on the left, which is the tip of Africa and the entry to the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea (which I crossed in 1928). Now we are crossing the Arabian Sea north of the Maldives and Laccadive Islands. All these names are known by people who were educated through the Royal Readers. We eventually crossed the Equator and on 26 November 1949 we saw India, arriving at Goa harbour (Marugoa) which is ruled by the Portuguese. We stopped for a day, on a Saturday and toured the city, seeing the buildings which were built by the people of Vasco da Gama. We were walking under tall coconut trees. This was my first time to set foot in the land of the Indians about 100 miles from Bombay.

Bombay

We travelled for a day and entered Bombay on Sunday 27 November 1949. When this ship enters a harbour, it is led by the pilot who is usually a white man but today it is an Indian. From here on we never saw a white man in a position of authority, not in the customs office, nor in immigration and passports. The officers were gentle to visitors, unlike the officers at home who always sulk when they see a black person. From that day, I became happy in a land which is ruled by its own people.

As you approach Bombay from the sea you see a big stone structure known as the Gateway of India. This was the route taken by important British people who were visiting India when the English were in power here. You see this structure from a distance and it looks impressive. The officers quickly dealt with their business, and members of the committee welcomed us warmly and garlands were placed around our necks. We were led to big cars and started seeing that immense city with its five million people, which is only smaller than Calcutta and London in the British Empire. To gauge its size, take into account the fact that each year 62 000 pupils complete their matric. Understand that in Cape Town, each day there is only one train that travels the distance equal to travelling to Rhodesia (on the main train line) but in Bombay there are 21 such trains per day and 300 local trains.

Various sights

We travelled through the main street, the Mahatma Gandhi Road, a name which has superseded an earlier English name. In a large street lined with impressive buildings, we saw a huge cricket field which can seat 200 000 people. It is the biggest field in Asia. Although it was Sunday, the people were playing and playing well. This reminded me of an accomplished cricketer, the late Ranjintsinji whom I saw in England in 1905 when I also played cricket.

In India Sunday is observed by Christians only. Most people worship Buddha, Mohamed, Confucius, Krishna, Laotse and many other saints who lived before the birth of Christ and they observe their own days in the week. Therefore, there is no stoppage for business, sport, railways, courts, building of houses and cultivation. Although the streets are wide, they are fearfully crowded by various means of transport, trams, carts drawn by buffalo which I saw for the first time, rickshaws which are like those in Natal but are drawn by bicycles. There are gigs which are drawn by one horse and horse carriages of the older type (1913) which were last seen in Cape Town in 1923. There are also various sorts of cars which go fast. There are cows and goats, which roam around in the streets all the time. But what is surprising is that there are no accidents. Drivers travel fast, hooting as they go. These cars are driven even by old men with grey hair, and by Sikhs who wear heavy headgear. I was sad to see thin horses which draw heavy loads.

The heat

In Bombay, the sun was unbelievably hot. It feels as if one has opened the lid of the fire of Nebuchadnezzar on the Plain of Dura: you sweat, even if you are in the shade. In the morning, I had seen my friend Manilal Gandhi packing away all his warm clothing and putting on white clothing: a white jacket, calico apron, shorts with big bottoms which are worn in India and are known as doti. I envied him, because I wore very warm clothing and I was as hot as a stone. The committee accommodated us at the home of a doctor, whose quarters were on the fifth floor. These were kind people, who warmly welcomed us with cold drinks. We conversed mostly about Africa.

~~~

About the book

In November 1949 DDT Jabavu, the South African politician and professor of African languages at Fort Hare University, set out on a four-month trip to attend the World Pacifist Meeting in India.

He wrote an isiXhosa account of his journey which was published in 1951 by Lovedale Press.

This new edition republishes the travelogue in the original isiXhosa, with an English translation by the late anthropologist Cecil Wele Manona.

The travelogue contains reflections on Jabavu’s social interactions during his travels, and on the conference itself, where he considered what lessons Gandhian principles might yield for South Africans engaged in struggles for freedom and dignity. His commentary on non-violent resistance, and on the dangers of nationalism and racism, enriches the existing archive of intellectual exchanges between Africa and India from a Black South African perspective.

The volume includes chapters by the editors that examine the networks of international solidarity—from post-independence India to the anti-colonial struggle in East Africa and the American civil rights movement—which Jabavu helped to strengthen, biographical sketches of Jabavu and of Manona, and an afterword that reflects on the historical and political significance of making African-language texts available to readers across Africa.

Publication support for this project was generously awarded by the AW Mellon Foundation in collaboration with Northwestern University and the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Grant from the University of British Columbia, Okanagan.

‘A remarkable travelogue by one of South Africa’s greatest intellectuals, DDT Jabavu, this book opens new vistas on Indian Ocean histories. Available for the first time in isiXhosa and English, this historical gem enriches our sense of the scope and scale of South African letters.’

—Isabel Hofmeyr, Global Distinguished Professor, New York University and Professor of African Literature, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg‘A significant figure in Cape African politics at that time, and a renowned academic from Fort Hare University, Jabavu’s expressive account of this trip weaves together a myriad of encounters with people he already knew, and those he would meet on his journey from the Eastern Cape to India, via the East African coast. One can only marvel at how the editors have re-enlivened Jabavu’s account of his epic 1949 journey—a rousing read!’

—Luvuyo Wotshela, Professor and Head of the National Heritage and Cultural Studies Centre, University of Fort Hare