I don’t believe any biographer can be objective.

—Mark Gevisser

… I saw a sign over a door in café lettering … I went in; a rather dingy room, hospital green. Admission R10. I had already arrived in Johannesburg, but now I felt I was home.

—David Coplan

Non-fictional literature, at its best, is porous, irregular and abrasive. It may be a pleasure, but it is not comfort.

—Luc Sante

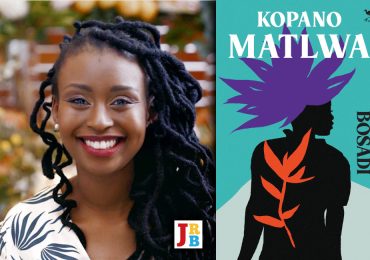

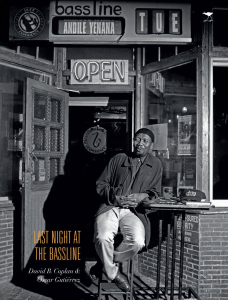

Last Night at the Bassline

David Coplan and Oscar Gutierrez

Jacana Media 2017

Late-1980s-early-1990s Johannesburg became the home of little jazz juke joints and blues cafés peopled by nocturnal crawlers. With the end of the rainbow that never was, the clubs went bust—their patrons either grew up, died or became world famous authors, musicians or crack-heads. One of the survivors, Bongani Madondo, reads a new book on the life and times of one such joint, the Bassline, and throws his bones

Jazz joints, historical and contemporary—juke joints and salons harking as back as far as the Harlem Renaissance; digs such as the Cotton Club in New York; Istanbul’s Jazz Age Pera Place; 1960s London’s Ronnie Scott’s; Jozi’s Kippies in its swing times—are, architecturally and metaphysically, existential worlds on their own.

They wear their singular attributes on their sleeves; they love their small-but-committed tribes. They demand devotion from both reveller and artist and, even more, a chunk of soul and flesh from the one inspirational fool who thinks he or she can take on the hazardous task of running one.

While there’s no such a thing as a typical jazz joint, there is a prototype at least of the people who inhabit them. David Coplan is one.

Coplan is a searcher, a seeker, a sniffer for the new blue note, the new players, new innovators and, of course, as a trained anthropologist and cultural archaeologist of the forgotten pasts and how they intersect with the bubbling new and hip presents, he is, in jazz speak, a digger.

He digs for a living. But he digs not out of intellectual obligation. Not unlike the late, great author Robert ‘Bob’ Palmer (see especially Deep Blues and Baby, That Was Rock and Roll), Coplan’s digging is not disembodied academic textual research—not that there’s anything sinister about that project.

Rather, Coplan is a player, a musician—well not quite a great one perhaps, but an interactive performer, a knowledge seeker, who has shared the stage with the likes of Philip ‘Dr Malombo’ Tabane and had some close, musical and personal encounters with the understudied and underappreciated 1960s-1980s guitar magic-man, the insouciant Allan Kwela, among others.

This is not to say these interactions purchase for Coplan, a white American transplant to South Africa, some kind of ghetto-pass. Cause they don’t—a fact he owns up to in his lively history of Bassline:

So did I learn […] why I had been put on this earth, and not just any earth: South Africa, though I would never be indoda yom’ hlaba lo (‘a son of the soil’).

Our collective letters are replete with witty, sardonic and wistful tales about the lives of jazz clubs, often shrouded in romance, which plays a key historical role in the narrating, re-narrating and ultimately the formal study of jazz and its commercial, artistic and spiritual offshoots: personalities, sartorial trends, and so on. No different here, for it is to romance—along with in-depth research and reliable (and unreliable!) oral retellings—that Coplan explicitly turns in this down-memory-lane project.

It is safe to suggest that historians and other academically-trained intellectuals generally have a hard time dealing with romance. It is looked down upon, discarded, left to the realm of fiction, or at best to maudlin memoir. But romance is, to be sure, at the heart of any biographical undertaking, and Coplan mines it, invokes it as one of his primary activating tools for research, and the results are instructive. Last Night at the Bassline is both a biographical sketch of a man and woman—Brad Holmes and the ‘uptown girl’ Paige Dawtrey, without whom Brad’s dreams would have evaporated into smoke, weed, or the omnipresent smog hanging over the city—and a place, Johannesburg.

It is also a period slice of optimistic climes long past by and, considering the racial and political state South Africa is in right now, perhaps never to be regained.

This is not to fall into the fiction held by my fellow liberal white South Africans and their black cohorts’ tendency to reminisce about ‘the good old days’. Post-1994 was only the ‘good old days’ for a specific people: Middle Classes across the racial strata. For the poor, the peasants, the shack dwellers, and those on twenty-year administrative queues for government’s rickety and roof-porous RDP houses; for those racially spat upon and those robbed stone-cold by the black African government, post-1994 was nothing but African Psycho redux (sies!).

Coplan seems to understand these polarities instinctively. But also, as romantics, he and his subjects remind us that life is neither linear nor lived in neat silos. They remind us that within the attendant blues and chaos of the country in the last quarter of a century, and within some glimmers of not-so-misplaced hope and joie de vivre, culture, the performing arts—music—have played key roles in keeping all of us sane, dreamful, and aspiring to a working ideal of what this country can and should be. (Not that we have had a serious conversation about that. Not that we would agree even if we dared to.)

It’d be false to look at the story of South Africa in the last quarter of a century and find only horror tales. This book is no horror tale. It is not only about Brad and his heroic squeeze, or Brad and his band of brothers, all from a Krugersdorp family that deserves its own biography, headed by salesman daddy ‘Dick’ Holmes (who loved hooch and whom hooch made crazy), and stoic Afrikaner mother Machel Barlow. Brothers bound together by not just the pathos that all families luxuriate in and are repulsed by, but also the Afrikaner dorp they grew up in, and the fraternal antics that got them out of being conscripted into the South African army. It is about a legion figures for whom the dingy Melville club served as a formative place for learning the tricky art of live performance; it is about a host of social unknowns who picked up the art of getting by in the fast and lippy arena that is Johannesburg’s greater, dimly-lit, semi-public parlour.

Bassline played an unforgettable cultural service as a home-away-from home for musicians and artists of all stripes: Slam poets such as the Thabo Mbeki Renaissance-era, all-female, ass-kicking troupe Feela Sistah! Spoken Word Collective, avant-gardists such as Zim Ngqawana, Lulu Gontsana and Carlo Mombelli, new-wave innovators such as Moses Taiwa Molelekwa, Paul Hanmer, McCoy Mrubata, returning exiles such as Bheki Mseleku and Tony Cedras, and artists pouring in from the neighbouring frontline states; Gito Baloi of Tananas, Simba Morri from Kenya, Rokia Traoré from Mali, and so many more game-changers I would need to refill my virtual inkwell just to recall them here.

Post-1994 new-wavers were not the only ones who kept and fed the ever-restless space and its omnivorous spirit and soul. Holmes made sure to create gigging work and help put a plate on the table for seasoned artists such as Pops Mohamed, ‘Big Voice’ Jack Lerole, Jan ‘Johnny’ Fourie and Afro-fusion acts such as Sipho Gumede and his former bandmate Khaya Mahlangu. They in return endowed the place with their tried and tested art—and brands.

The beauty and subversion of the Bassline lay in its multivalent approach to the performance arts: For me, one of the most sublime moments in the club’s history happened one Sunday late-summer afternoon in 2002.

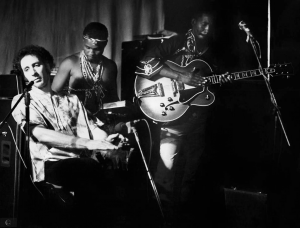

The performance poet and art critic Sandile Dikeni staged an adroit text and sound collaboration with the pianist Andile Yenana’s band. Audiences were treated to a blend of spoken bluesology, syncopated and arranged as jazz vocal stylings, undergirded by a tight piano-led trio—a performance so intense, so explosive, so challenging and so creatively cathartic it recalled 1960s Free Jazz collaborations in Manhattan lofts between the likes of Pharoah Sanders, Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler and Beat poets such as Bob Kaufman, Amiri Baraka, Ted Joans, Keorapetse Kgositsile and Larry Neal, among others, in and on the heart and periphery of the Black Arts Movement. Dikeni is to jazz what the Malian portrait master Seydou Keïta and South African photographers Alf Khumalo and Ernest Cole were to the visual arts in their time.

In Yenana, though, Dikeni met more than his match: he met his alter-negro. Calm, deeply reflective, bracing, searching … sniffing … digging, Yenana and his senior Ngqawana, as well as Molelekwa, quite simply revolutionised piano since Abdullah Ibrahim’s Water from an Ancient Well and (with Carlos Ward) Live at Sweet Basil Vol. 1.

While Dikeni made flights and leapt into abstract and magical-realist excursions, loose words and whole stanzas dancing off his tongue right into existential bebop and hip-hop, the Yenana Trio dug deep into the blues, with occasional trippings into classical … evoking both Igor Stravinsky and, closer to home, Sophiatown jazz greats such as the great Marabi originator Tebejane, down to ‘Zulu Boy’ Cele.

Just as with the Holmes family story, that performance too deserves its own book. And that’s the thing about this dingy club: Writing about it unlocks a torrent of memories and uneven, overblown emotions.

I am here guilty of that, and so is Coplan.

For example, he claims Melville was a Bohemian village. But was it? Or did he mean that the 7th Street strip, the suburb’s own Beale Street, was proto-boho, at best? He goes overboard more than once, and the familiar voices quoted like supporting acts in reminiscences of the ‘good punky ol’ days’ chorus with him. Like arts scribe Shaun de Waal, who knows the territory like the back of his hand … Jameson’s bar, The Yard of Ale, subversive punk types such as the Cherry-Faced Lurchers, Die Radiators, The Kerels, Khaki Monitors, Koos Kombuis and Johannes Kerkorrel, and my old colleague in journalism Bernoldus Niemand, Voëlvry’s own ‘Lizard King’.

To claim, though, as De Waal does, that Jameson’s U-shaped bar with the cramped stage at its far end was ‘the epicentre of a whole new South African youth culture …’, or that the party created at Jameson’s gave birth to the ‘unofficial soundtrack to the revolution’ is of course unadulterated bullshit. For if the jolly-good culture mix in the city was the epicentre of new South African culture, what then was happening in the townships, which have been creating tons of galvanising new jazz and pop sounds almost since Paris burned in 1968 and the Black Consciousness movement boomed into national consciousness?

‘Soundtrack of the revolution’—really? So what were Harari, Brenda Fassie, Chicco or Sakhile doing in the shacklanes outside the cities, if the sonic revolution was being brewed by the multi-culti white punks and their dreadlocked friends downtown?

Why does Coplan fall for that?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind: Coplan is a romantic. In romance not everything has to be remembered for what it was, it is the feverish climate in which those things happened that matters. And in that light De Waal doesn’t look so shabby after all.

Look, Bassline will be remembered for many things. I will remember it, sadly, as the place my long friendship with Moses Taiwa Molelekwa burst at the seams. Taiwa, who by then was fooling around with kwaito stars TKZee—a creative marriage I questioned—accused me of being a jazz snob and all sorts of things, not knowing this black rock negro knows pretty much fokol about jazz. But also I remember it for hanging out with good friends and regulars such as the late playwright and shit-hot columnist John Matshikiza, cultural scenesters such as Sifiso Ntuli, and the club’s—the era’s?—visual biographer, the inimitable Oscar ‘Cariño’ Gutierrez, mostly known as ‘Comrade Oscar’.

Gutierrez’s photographic meditations of the place and era provide not only a visual testament to the beauty and the beast that was Bassline, they also serve as a reminder that a place can never be free-frozen in time.

And yet, paradoxically, he achieves something like this: capturing and bottling up the joint’s thunder and lightning and the memories we are now gathered here to reminisce about. Gutierrez’s photos are pure raw-kin-roll. Perhaps because of rock’s umbilical connection to jazz’s vagabond, Beat-poetic mutual lover—poetry—we keep coming back to it to channel some imagery about jazz. Perhaps rock is the more animated stepson of jazz, thus more readily generous with its metaphors. Perhaps because it has not yet fully repaid its debt to the founding oracles of jazz and blues.

The heck? Consider this. One of the Afrikaner punk-poet-rocker James Phillips’ pals Carl Raubenheimer wrote of his mate after the tragedy and lousiness that was his death: ‘James was a saint who lived the life of a devil.’ Of course he was not. Of course it’s not meant to be taken literally. But within the man’s ribcage throbs the spirit of a well meaning, if idealist, soul. The same applies to Bassline. Its founding ethos and some of its operational pathos touched the soul … it was also, as is any decent jazz joint worth its name, a kind of hellish place to be. How hellish might best be shared by some of its patrons, some of whom actually died after the place moved home. Many great friendships were forged and many lost. Clearly, it did not manage to unite the country’s races, for that was not its task. It did, however, offer us a glimpse into what a space dedicated to the development of music, without major sponsorship or deep pockets, can achieve.

To Coplan, Paige, the irrepressible Holmes brothers, them molls and damn swells, artists and tall-tale-purveyors who—as per Bakithi Kumalo—’stepped on the bassline’ and lit this jazz digs its embracive spirit, we can only shout-out: Salute Soldados!

- Bongani Madondo is Contributing Editor and the author, most recently, of Sigh, the Beloved Country: Braai Talk, Rock ’n’ Roll & Other Stories.

Index

Authors

- Shaun de Waal, Mark Gevisser, John Matshikiza, Bernoldus Niemand, Carl Raubenheimer, Luc Sante

Artists

- Ernest Cole, Seydou Keïta, Alf Khumalo

Books

- Deep Blues, Baby, That Was Rock and Roll by Robert ‘Bobby’ Palmer

Music and Musicians

- Albert Ayler, Gito Baloi, Tony Cedras, Zulu Boy’ Cele, Cherry-Faced Lurchers, Chicco, Die Radiators, Brenda Fassie, Jan ‘Johnny’ Fourie, Lulu Gontsana, Sipho Gumede, Paul Hanmer, Harari, Abdullah Ibrahim, The Kerels, Johannes Kerkorrel, Moses Taiwa Molelekwa, Khaki Monitors, Koos Kombuis, Allan Kwela, ‘Big Voice’ Jack Lerole, Live at Sweet Basil Vol. 1, Khaya Mahlangu, Pops Mohamed, Moses Taiwa Molelekwa, Carlo Mombelli, Simba Morri, McCoy Mrubata, Bheki Mseleku, Zim Ngqawana, James Phillips, Pharoah Sanders, Sakhile, Igor Stravinsky, Philip ‘Dr Malombo’ Tabane, Tananas, Cecil Taylor, Tebejane, TKZee, Rokia Traoré, Carlos Ward, Water from an Ancient Well, Andile Yenana

People

- Machel Barlow, Paige Dawtrey, Brad Holmes, ‘Dick’ Holmes, Sifiso Ntuli

Photographers

- Oscar ‘Cariño’ Gutierrez

Places

- Kippies, 7th Street Melville, Beale Street<, Jameson’s bar, The Yard of Ale/li>

Poets

- Amiri Baraka, Sandile Dikeni, Feela Sistah! Spoken Word Collective, Ted Joans, Bob Kaufman, Keorapetse Kgositsile, Larry Neal

Topics

- Beat Poets, Black Arts Movement, Black Consciousness movement, jazz, rock ‘n roll, the blindness of romance, seedy jazz and juke joints and blues cafés peopled by nocturnal crawlers, Voëlvry, white American transplants to South Africa