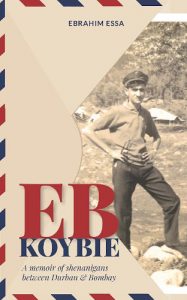

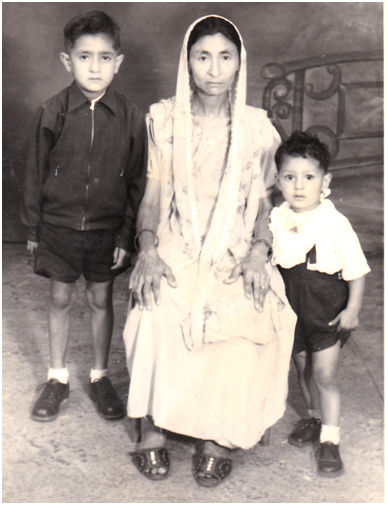

As part of our January Conversation Issue, journalist and author Azad Essa is in conversation with his father Ebrahim Essa, the author of a new book, EB Koybie: A Memoir of Shenanigans Between Durban and Bombay.

EB Koybie: A Memoir of Shenanigans Between Durban and Bombay

Ebrahim Essa

Social Bandit Media, 2019

Azad Essa: After editing your book for around five years, I can say I quite like how it turned out. But are you satisfied with the book, or do you think you should have given it to a professional to handle?

Ebrahim Essa: See, I gave you a manuscript of five hundred pages. You reduced it to around two hundred pages over five years. If you took three more years, the book would have probably been twenty pages long.

Azad Essa: So, you are not satisfied?

Ebrahim Essa: I don’t think a random professional would have understood the cultural references and nuances. All things considered, yes. I am quite satisfied. Thank you.

Azad Essa: Right. Great start. The book is called EB Koybie. And you will tell people it means ‘For that matter, him, too.’ But what is this book really about for you?

Ebrahim Essa: The stories came first. Then after I visited the waterfall in Mayville, that ran close to our old house, I remembered the strong connection to that spot and then felt that the book should be called ‘Waterfall’. The waterfall is somehow synonymous with my earliest years. It was as if I had been born there. But then book expanded. I wrote about the teenage years going on to pick on almost all members of my family. I realised that the book wasn’t just about me; it really was about everybody else, too.

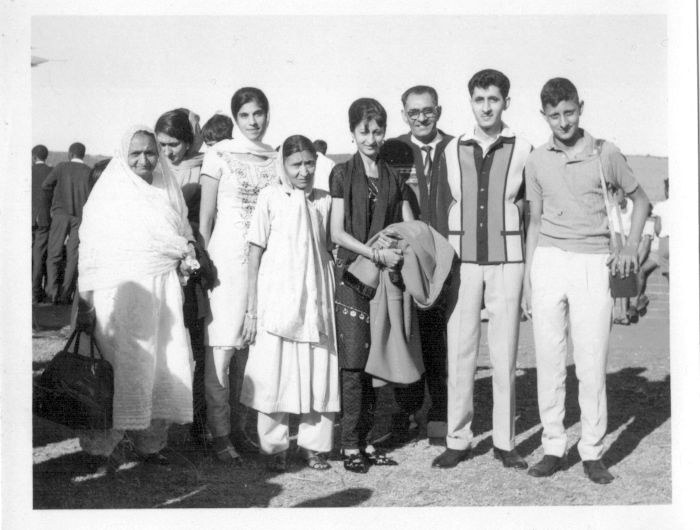

Azad Essa: EB Koybie is divided into two parts and five chapters. One part is in Durban and the other part is in Bombay. Do you feel split between these two places?

Ebrahim Essa: Leaving Durban around 1965 and landing in Bombay was mind blowing. Nothing resembled Durban. Firstly, there were only Indians in every direction. Secondly, it was massive. Millions of people trying to make it in this mad city. There was no continuity of any kind between the two cities and the two countries. When I returned to Durban in 1969, I faced the reverse problem. The city had changed so much on my return. My friends had moved on and vanished. So I returned to another lost city. I have been back to India a number of times, visiting family in smaller towns and villages. After a while you realise that life is not really different wherever you are.

Azad Essa: When we spoke about you writing a book, you were not completely sold on the idea. Then you jumped right into it. And the ideas and memories just flowed. How do you manage to remember such detail from sixty years ago?

Ebrahim Essa: I can’t explain that. I think I took my childhood seriously. I had lots of insecurities. My father wasn’t around. My sisters and mother used to terrify me with stories of devils and witches and ghosts. Then there was a lot of talk about the 1949 riots, which made us all feel insecure, especially given Father wasn’t around. I also had terrible asthma and struggled immensely with my breathing during the early days. I was almost always wheezing. I think I remember so much because it was a question of survival and it was all a struggle.

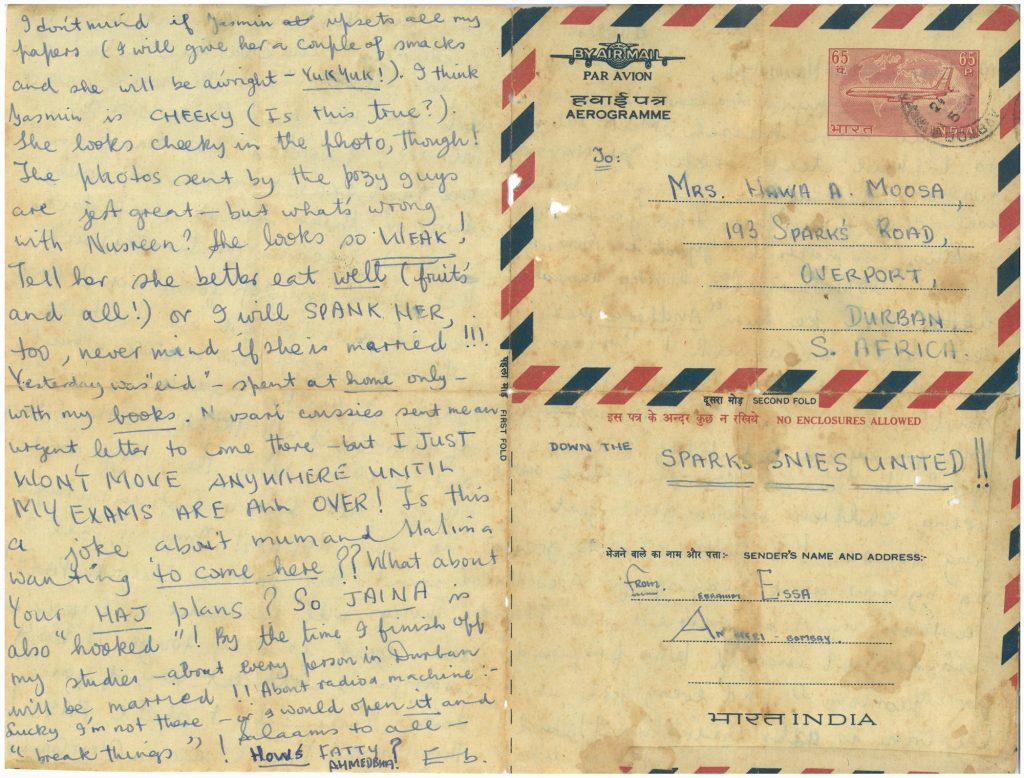

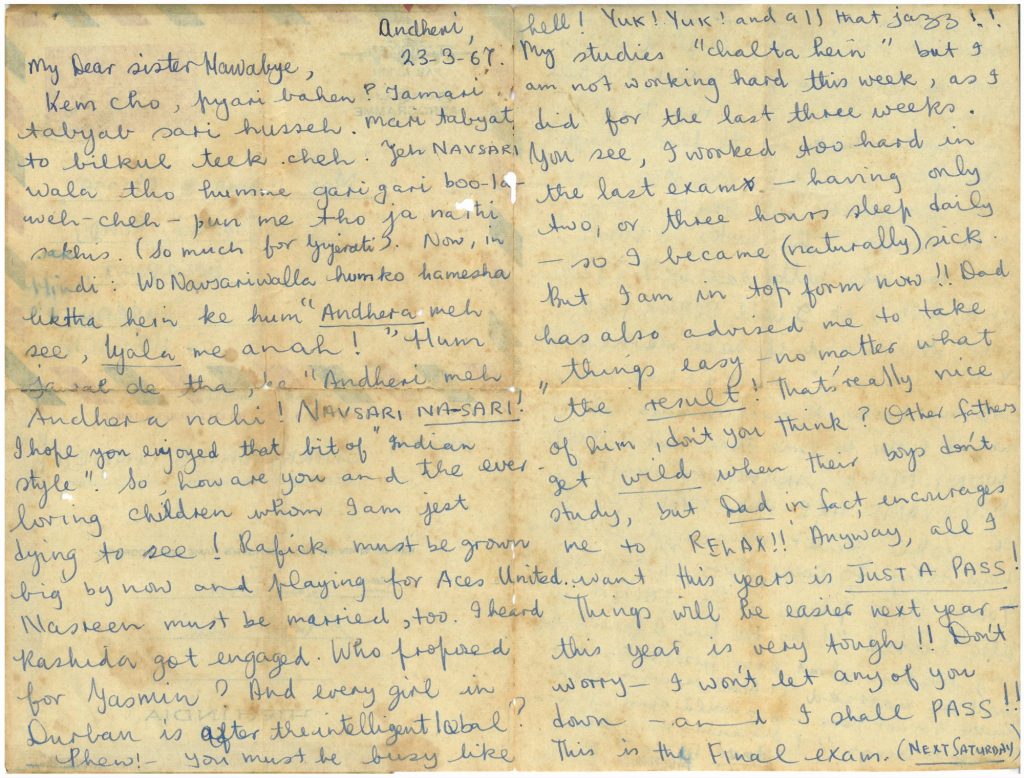

Azad Essa: The book took you two years to write. But this project began a long time ago. You actually wrote a short biography about your father in 1979. I also know you had diaries from school and student days and dusty comics that mapped out a previous life. Then one day, you mysteriously threw a lot of these away. Why did you do that?

Ebrahim Essa: It wasn’t really much of a mystery. I think it was part of my anti-clutter drive in the nineteen-nineties. Or maybe it was because I had more important things to think about. I was married and we had you and your sister Shenaaz. Priorities had changed. There was no time to think about the past and peep at diaries.

Azad Essa: For someone so attached to memories, I find that odd. Why would you give up on a few boxes?

Ebrahim Essa: To be honest, it is also possible some boxes got mixed up and I threw away more than I had meant to. Once it happened, I think I just let it go. I also found that some of my letters to newspapers were fading and no one seemed interested in them, so I just let it go.

Azad Essa: That is a pity. But in the spirit of moving on, you became a school teacher in the eighties and spent many years teaching physical science at high school. You still wrote letters to the newspaper, but I also remember you telling many stories in class. Was this your way of bringing in your love for storytelling into your daily life?

Ebrahim Essa: Yes, absolutely. I was interested in the lives of scientists and inventors. And given that maths and science are rigid subjects, I wanted to draw the interest of those who may not naturally be drawn to the subjects. So I would look for some eccentric details about these scientists and I would bring them into the classroom. Teaching Newton’s law involved maybe a story about his relationship with his family and how he left home to pursue his dreams, or locked himself up in a room and ‘discovered’ calculus. Many of my introductions to new modules or concepts would start off with a story. And it used to attract attention. Students used to ask me jokingly if this was a science class or a class on literature. And of course they loved it because students love everything but the syllabus. But I see it as getting them interested in the subject.

Azad Essa: That is nice. But did your students pass?

Ebrahim Essa: Yes, of course. I had excellent results, always.

Azad Essa: Let’s talk about religion. As a child, you embraced your Indian identity, but it is a little different when it comes to your Muslim identity. Here you struggled, especially in the classroom. You also resist dogma. Why is that?

Ebrahim Essa: You see, religion is primarily taught by parents. My mother read her prayers, but she didn’t force me to do anything when it came to religion. She was very ritualistic and superstitious; things she carried with her from India, I guess. To keep out the evil eye, she would take eggs and rotate them above your face and then throw them. This is something my father hated. And that is actually another thing. Fathers usually take their sons to the mosque. But in my case, my father was not staunch about religion. And in the early nineteen-fifties, I had no idea where he was. Later, I realised he was in India. So when I entered madressah and watched others, I felt out of place. Maybe I resisted because I didn’t have a background in it. You can say I am very happy about it.

Azad Essa: Religion is just one theme covered in the book. You also cover apartheid and the Group Areas Act, which saw the family kicked out of Mayville and forced to move to town. But you don’t spend much time talking politics. You don’t labour on the political context. You focus instead on the life that you lived. You write about Hindi cinema that gives you comfort, comics books that stimulate you and let you escape. Does it feel odd to be nostalgic about sad times?

Ebrahim Essa: I was accidentally introduced to Hindi music. We had one gramophone and maybe two records lying around. Most of the music I heard was from neighbours who could afford 78s. The sounds I remember or associate with that time came from neighbours and they form the background score of those trying times; of confusing domestic violence, bullying and the sheer loneliness of the time. This was around 1950 to 1953. I was alone with my Ma at home and the others were at school. I played with empty cans to pass time. Amid that silence, Indian music became intrinsic to my life.

Nostalgia is something that is very personal. And I doubt that any psychologist can fully explain it. I doubt that people who come from super affluent or stable homes recall things from their past. Nostalgia is a bittersweet event. We long for the good but deep down that past is surrounded by a sad event. The mind blocks out the sadness, and we try to focus on the nicer events.

Azad Essa: There are many people in the book who have now passed on. People died between the first draft and publication. You were upset with me for taking so long with the edits. I am sorry about that. Whom do you wish was still alive to see the book?

Ebrahim Essa: Notable persons to pass on before the book got published were my three uncles: Ahmed, Mohamed and Ismail. They each feature in the original manuscript quite prominently. My uncle Ismail introduced me to projecting home movies all those years ago. He also taught me how to operate an 8 mm camera. Uncle Mohamed was a reckless adventurer. And Uncle Ahmed was not only the resource centre to research the roots of the family, but he was also instrumental in encouraging me to read books. He made me read Jock of the Bushveld. Some school friends also passed away. One notable friend was Ebrahim Madari, who also features in one of the stories.

Azad Essa: What about your parents? Do you think your father would have enjoyed your book?

Ebrahim Essa: Of course, he would have. I regret a lot. I am seventy-four years old and my father passed away when he was only sixty-three. And like this, he missed so many things. He didn’t see me become an instrument technician and then a teacher. He didn’t see me get married and meet you and your sister. There was no VCRs or DVDs or memory sticks in those days. He would have loved home cinema.

Azad Essa: Speaking about your father, there is this incident in the nineteen-thirties. He smuggled gold under the chassis of a car to Madras. But then he got caught and deported. You hold him in very high esteem despite him being so absent from your life, especially during the early days.

Ebrahim Essa: About that smuggling episode, I don’t think he was after ‘wealth’. We were very poor. And I think he was just trying to uplift us and therefore took a chance. It didn’t work out. He didn’t have a bone of dishonesty in his body yet decided to challenge the Indian government by trying to take gold into the country.

My father was an enigma. If one reads the story of my father, which makes up the last chapter of the book, one would realise he was neither a father of a past, backward era nor was he a father of the present backward era. He was against all forms of dogma. Another thing I learnt from him was a love for India. His heroes were Nehru, Gandhi and Maulana Azad. He told us that they were not perfect, but meant to get the country on a better track. He also reminded us that we had descended from Hindus and we were not to look down on any race or religion. Religion was circumstantial, he said. He also only studied until grade 4. But he made sure his children received a good education. That is why I am in awe of him.

Azad Essa: But you know Gandhi was racist, right?

Ebrahim Essa: Probably. I told you that he said that these guys were not perfect!

Azad Essa: Moving on. How has the book been received? And are you accepting all the lies from friends and family that the book is ‘wonderful’ and ‘amazing’?

Ebrahim Essa: You can’t judge a book just after a launch. Most books purchased during launches remain sealed on the book shelf. But I have received some thoughtful feedback from people who say they read the book and enjoyed it. And I am receiving feedback from all corners. The book is doing okay, it seems.

Azad Essa: Are you surprised?

Ebrahim Essa: Yes, of course I am surprised. I thought just the immediate family would be interested in it. You told me that there was a gap for this type of book. I didn’t believe it. And I just went along with it. But it seems you might have been right, for once.

- Ebrahim Essa is a comic book and Hindi film aficionado based in Durban. He taught high school physical science for thirty years before retiring in 2016. He is a widely published letter writer to various newspapers across South Africa, the author of The Life Story of Suliman Essa Patel and was also a contributor to the anthology Undressing Durban (Madiba Press, 2007). EB Koybie is his first book.

- Azad Essa is senior reporter for Middle East Eye based between Johannesburg and New York City. He was previously based in Doha with Al Jazeera between 2010–2018. He is the author of Zuma’s Bastard (Two Dogs Books). Follow him on Twitter.

One thought on “[Conversation Issue] On writing about religion, childhood and insecurities: Azad Essa transcribes a conversation between father and son”