As part of our January Conversation Issue, Wamuwi Mbao chats to Nicole Dennis-Benn about her work, the process of writing believable characters, and what it means to write about marginalised people.

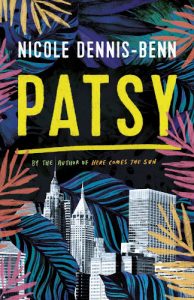

Dennis-Benn is the author of the acclaimed 2016 novel Here Comes the Sun. Her second novel, 2019’s bestselling Patsy, details the travails of its eponymous character as she leaves Jamaica to seek out a better life for herself in the USA.

Patsy

Nicole Dennis-Benn

Oneworld, 2019

Wamuwi Mbao: I’ve brought a stack of questions, Nicole.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Really? Oh Gosh.

Wamuwi Mbao: Yeah. Gotta be prepared.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: I’m prepared—I mean, I read your review. It was such a good review. but I read the part where you didn’t like Tru …

Wamuwi Mbao: The problem with writing reviews is that you’re always constrained by time, and I could have written a five-thousand word piece where I went into more detail. I loved Tru as a character—I actually wanted to ask you more about her—but it’s one of those things where I had to decide how to express a critique without giving away too much of the book …

Nicole Dennis-Benn: That’s true. I hate reviews that give away too much of the book …

Wamuwi Mbao: So I’m like, how can I build in enough detail here without giving away too much. As soon as I read the review I thought—I weighted this too much towards Patsy. If I could do it over, I’d give more attention to Tru’s story. She’s such an interesting character.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: I’m glad you think so—I really wanted to give Tru her own light—I know the story is mostly about Patsy and her mother, but I wanted to give Tru her shine as well.

Wamuwi Mbao: I think you did do that—you definitely gave her space. I was on a panel the other day and we were discussing how one builds believable characters, and I kept referring to your novels, because this is something you do well. You don’t make the characters one-dimensional: even when they’re people you don’t really like, you still think ‘oh, but this is a person’.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: At the end of the day, I really wanted to tap into the fact that Patsy ends up coming into herself. When Cicely shows up at the end, it’s more for Patsy to realise that ‘I’m more than this’. Her gravitation towards Cicely in the beginning is because of her complexion and Patsy’s internalised low self-worth, as a Black girl aspiring to be liked by the kind of light-skinned girl who looks like that.

Wamuwi Mbao: I know; when Cicely shows up again, I was sitting on the edge of my seat going ‘Oh no, she’s back again!’ It was a bit of a cliffhanger.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Exactly—I wanted Patsy to realise that she had to grow. So when Claudette tells her to go, she wanted to challenge Patsy to do better.

Wamuwi Mbao: I felt so bad for Claudette because she comes into Patsy’s life at this really low ebb, and she brings so much joy.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Right? I wanted them to work it out.

Wamuwi Mbao: Patsy is your second novel, following on from Here Comes the Sun. Would you say something about your journey from that novel to this one? What did it involve for you as a writer?

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Here Comes the Sun was that book I had to purge from my system to get everything else flowing. That book was such a part of me. Here Comes the Sun tackled the issues that I grew up with in Jamaica, and so it was a way to answer those questions myself, to talk about classism, colourism, the sexual violation of working-class Jamaican women, the way our tourism industry marginalises the disenfranchised while they’re building their big hotels … I wanted to write against this notion of ‘paradise’. It was a cathartic process.

Wamuwi Mbao: Yes. That comes across.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: And there was a time during the writing of Here Comes the Sun when Patsy started speaking to me—that was around 2012, when I was trying to get Here Comes the Sun to my agent. Patsy is a confessional about a woman who is an undocumented immigrant in the United States, who had so much to say about her experiences. But what the novel wasn’t revealing to me at that point was that she’d left her daughter behind in Jamaica. I grew so obsessed with this character that I kept writing these drafts of her voice. The book stayed with me for all that time, and I was starting to write it when Here Comes the Sun made a big splash, and somehow I knew I had to protect Patsy, because I had that crippling fear, you know? Like, ‘Can I do this again?’

Wamuwi Mbao: And that’s always the pressure that you’re faced with, because as soon as you have one success, people will say, ‘Alright, what’s next?’

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Exactly! And I’m sure other writers have that moment where you go—do I move forward, leave this story? What do I do? And Patsy still was persistent, and I spoke to my mother and my wife about how I was always fighting with Patsy, and my mother said, ‘It’s like having children. They’re going to each have their own lives, and you have to accept that.’

Wamuwi Mbao: That’s a lovely way of thinking about it.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Yeah, and because of that, I was able to finish Patsy and put the novel out into the world.

Wamuwi Mbao: I definitely enjoy your novels because of their depictions of ‘worlded women’—you have women in your stories who aren’t one thing or the other—they’re not necessarily likeable, or virtuous, but they’re truly human. I pick up an investment on your part in thinking about how to represent women more fully than they’ve tended to be.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: I write against these unexamined notions of womanhood and femininity—my writing asks who defines these categories. And so you see someone like Margot in Here Comes the Sun, was someone I wrote out of the box. She’s a highly sexual woman who’s not using her sexuality as a weapon. Patsy on the other hand is less articulate in how she feels about women claiming their identity before motherhood. I seek out these women who tend to make unpopular decisions in my writing because they’re more interesting to me. I’d rather write them than the church lady or the perfect wife.

Wamuwi Mbao: Patsy as a character is particularly interesting because she’s unapologetic about not wanting to be limited by her circumstances, but that places her in tricky situations that play out over the course of the novel: she has a daughter, but she also wants a better life than her very limited social circumstances provide for her, and so she’s caught in this conflict that speaks exactly to what you were saying, about the expectations of womanhood and about how she should be as a mother.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Exactly. Zora Neale Hurston talks about how we write to answer questions of our own. Patsy was my way of doing that. It helped me to make sense of my own biases where defining womanhood is concerned. I kind of explore through her experience, vicariously.

Wamuwi Mbao: I find it really interesting that, where the context for Here Comes the Sun was Jamaica and the kinds of internalised exploitation that goes on there, with Patsy you’re shifting that site of conflict, because you have this character travelling to America, and entering into those narratives about the land of opportunity. Of course, so many of us go there and we find that it’s not that and it becomes this totally different thing. So what does it mean to write a novel in this time where the role of the immigrant is so fraught, especially featuring a character trying to make her way in an America that is starting to become more hostile?

Nicole Dennis-Benn: The funny thing is that Patsy occurred to me in 2012, well before the current administration. No American administration has been friendly towards immigrants.

Wamuwi Mbao: Yes, she arrives at the tail-end of the Clinton era …

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Exactly. And that was something I wanted to document because I lived through it. My own father was an undocumented immigrant driving the taxis in New York City before he married an American woman, and that was how we were able to get there. So it was more important for me to tell that working-class immigrant story, because they’re not coming over as privileged. They’re starting from scratch. When I saw those lives depicted elsewhere, they often seemed so perfect, and I think that existing as a Black or Brown body, you almost need to be god-like to be accepted by white people or white readers, and I thought No! Let me put a Patsy on the page, who is a highly complex Black working-class mother, who refuses that role. I wanted to think about how such a person is received: is she still worthy of a place to fulfil her dream? And that’s where I was going with this novel.

Wamuwi Mbao: So what about Tru, the daughter who is left behind?

Nicole Dennis-Benn: I wanted to write Tru’s story because you usually hear the immigrant’s story, but the narrative of the child is equally important. You know, people will say ‘you ought to be grateful, you shouldn’t be missing that person’, and so on. I wanted to pour all of that into Tru. In her case, she was literally abandoned, and so I wanted to give her that yearning and longing for her mother, as she comes of age in her community without Patsy. It was really fun to write Tru, and also to create this character who lives outside of her gendered box—

Wamuwi Mbao: —Which is fantastic. The layers of truth you build into her character as she grows up and develops her sense of her place in the world is really compelling. I like that you resist immersing Tru in the tropes of rejection and discrimination.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: I wanted to put something different on the page. You know, back home we have what we call the Gully Queens, these LGBTQ youths on the streets of Kingston who are marginalised and threatened. I didn’t want that to take the story somewhere else. I wanted Tru to grow up in this community where she’s protected by her father, Roy.

Wamuwi Mbao: Who is also this conflicted character. The relationship between Tru and Roy is filled in by these surprising moments of intimacy. Roy is macho and patriarchal, but he’s also a caring father, even as Tru begins to develop her own identity, wearing her hair short and being more physical. You have that wonderful scene where the father and daughter are out running together, and there are very few words, but it’s fantastic.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: I was writing against a lot of tropes. People always ask me about the irony of Patsy and Tru living so far apart and both being queer, and while you were saying this I was thinking that Roy actually was the better parent for Tru. Patsy would have seen so much of herself in Tru, and maybe would have wanted to take that out of her.

Wamuwi Mbao: I have to ask. Your depictions of mothers are often conflicted or troubled. I sense that you’re keen on troubling the easy expectations of what motherhood should involve or what motherhood should look like.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Definitely. I mean, if you take Dolores in Here Comes the Sun, people thought, Oh my God what a cruel mother, but that was how she thought she could love. We tend to mother how we were mothered, and Dolores internalised so much of that postcolonial scarring, and she imparted that to her daughters, this idea that ‘nobody’s going to put you on a pedestal as a Black woman, so let me be the first to break you’. With Patsy, something similar happens. She feels Tru would be better off being raised by Roy, because she feels like she has nothing to offer. These characters allow me to explore intergenerational trauma—I feel like it’s important to see the patterns that repeat themselves over and over again, through those relationships.

Wamuwi Mbao: I think that definitely comes across with your older women characters. You’re not unsympathetic to them, whether they’re bible-thumpers who’ve immersed themselves in Christianity or other things. They’re wonderfully readable because you have this push-pull response to them.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: It’s really about giving them context. I work really hard to make sure that everybody has their share of good and bad.

Wamuwi Mbao: I want to talk about Jamaica as a setting and as an intertext. Obviously, in Patsy it functions as a more complex world than simply ‘the space one leaves’. For the people who are left behind, they have to negotiate this world and its diverse cast of characters.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: One of the things I wanted to capture with working-class Jamaica (which I tried to do in Here Comes the Sun too) is that, while it is a beautiful country, we’re still dealing with what it means to live in a space where upward mobility is almost impossible. You have characters looking to other countries like America, Canada or the UK, but if you can’t get there, if you can’t get a visa, then your refuge is the church. And that’s where a lot of the characters see their salvation—even the church becomes a way to be somewhere else. And that was why I felt that you had to tie immigration and religiosity hand-in-hand, because they work together.

Wamuwi Mbao: I want to think about Patsy’s growth towards self-worth as an important motif in this book. We start out with her as someone who doesn’t feel appreciated and isn’t in a society that is able to really appreciate her, but then travelling to America doesn’t bring the expected panacea. She undergoes many painful lessons to get to a point where she understands herself.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: It’s really about unpacking what home is. Patsy thinks that by leaving, she’ll find a better situation elsewhere, only to find herself enduring similar hardships abroad. I was playing around with the idea that for the Black female body home isn’t really anywhere, when her self-worth is so devalued, until she ultimately finds home within herself—that’s where the growth takes place. Because she’s on the margin wherever she goes, she realises that the happiness has to come from within. Not to sound clichéd, but it was important to me that Patsy, as a woman who didn’t have much choice when it came to motherhood, was able to grow and reach that point.

Wamuwi Mbao: Reading through Patsy, I was struck by this sense that you’re archiving a very particular time in America’s history—the late twentieth century—and what that time meant for a group of people who don’t often see representation. You go into those places in America where the immigrants make their lives, and you touch on gentrification and those other cultural happenings, as they are experienced by Patsy and the other characters. It’s a time that tends to be overshadowed by spectacle—stories like the Amadou Diallo murder and that sort of thing—and you bring attention to the ordinariness of life during that time.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Yeah, I really wanted to have the reader walk in Patsy’s shoes. When I first landed in America, it was the day-to-day loneliness that really impacted me. It was a painful adjustment, and I didn’t want to gloss over the fact that it’s really hard, especially if you’re sold this idea that the place will be a salvation. People ask me why Patsy didn’t just leave, and I think it’s important to realise that a lot of us can’t leave—it would be a great shame upon your family to see you coming back empty-handed.

Wamuwi Mbao: That’s something the story handles in a really successful way, the idea that there’s a success narrative that accompanies what being an immigrant means, and that places an immense burden on you.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Exactly!

Wamuwi Mbao: There’s a wonderfully awkward moment where Patsy walks into a grocery store and she comes across someone who’s supposed to be a bank manager—

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Ducky!

Wamuwi Mbao: Yes, and they recognise each other, but he’s packing the shelves and she’s with her queer lover, so then they have this I-won’t-tell-if-you-don’t moment.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: The lies we tell ourselves as immigrants, and the lies we tell each other … I remember those letters coming in the mail, and it would be pictures of people posing in front of mansions or Mercedes-Benzes. And you think, ‘Wow! If America gives them that, I want to be there too!’ It was a fun scene to write, but a sad one too.

Wamuwi Mbao: So in closing off, I want to ask you about the public life of your novel. I follow you across various social media fields, and it’s quite life-giving—especially when you enjoy a novel—to see other people wanting to share that experience with you. The community of readership that is building around your books is great to see.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: [Laughing joyfully] Thank you!

Wamuwi Mbao: I mean it. You give your novels space for people to appreciate them, and when I reviewed Patsy, I had so many people coming up and wanting to talk to me about the book …

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Really? I love that.

Wamuwi Mbao: Yes, it shows that you’ve sparked some kind of joy with people.

Nicole Dennis-Benn: You know, there’s that ever-present anxiety we have as writers, where it’s just you and the page. And Here Comes the Sun did exceptionally well, but then I was left feeling like I had to protect Patsy in this bubble where I wasn’t thinking about the positive or the negative reviews, and being true to those characters. I really hope that what people take away from these novels is a greater sense of empathy—that they can connect with what I’ve written.

Wamuwi Mbao: And my final question is a selfish one, but I’m always interested in what people answer. So who are you reading at the moment?

Nicole Dennis-Benn: Warsan Shire’s Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth is a bible for me at the moment. I also read a lot of memoirs—I’m reading Jeanette Winterson’s Why Be Happy When You Can Be Normal? When I’m not writing, I read a lot, or if I don’t read, I go to museums. They feed into each other.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.