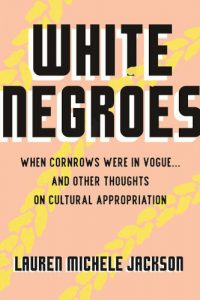

As part of our January Conversation Issue, Lauren Michele Jackson talks to Khanya Mtshali about her new book, White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue … and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation

White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue … and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation

Lauren Michele Jackson

Beacon Press, 2019

In White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue… and Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation, writer, critic and scholar Lauren Michele Jackson reframes the way we think and talk about cultural appropriation. From the moment Miley Cyrus twerked against Robin Thicke at the 2013 Video Music Awards in Brooklyn, New York, thinkpieces, essays and threads spun the term into something of an accusation—a convenient descriptor for a practice we shouldn’t like. For Jackson, however, that unlikable practice isn’t necessarily cultural transport or exchange (which we all partake in), but rather the ability of one group to profit off of black culture, aesthetics, modes and language in a way that black people cannot. Jackson goes on to explain how theft of black cultural production can often be a matter of ‘inattention more than intention’, yet embody systems of oppression like racism and global capitalism. At just under two-hundred pages, White Negroes is a smart, generous and witty investigation of America’s longstanding tradition of adopting ‘black aesthetics without black people’. For The JRB, Khanya Mtshali talks to Jackson about her book.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Khanya Mtshali: You’ve produced some of the most compelling essays on cultural appropriation in the last few years. This book is no different. I’m curious to know what prompted you to write about the theft, for profit, of black cultural production. Is this something you’ve been thinking about before ‘cultural appropriation’ became a thinkpiece-friendly buzzword?

Lauren Michele Jackson: I think it happened quite organically. I wasn’t really freelancing when ‘appropriation’ took off as a buzzword in 2013, around the time of the Miley Cyrus performance. I wasn’t doing much writing aside from my academic work. Appropriation wasn’t something I latched onto until I transitioned into writing for the media. I became fascinated by cross-racial aesthetics and cross-racial identification and pollination, which happened to coincide with what I thought were unrigorous debates, conversations and thinkpieces about appropriation. When it came time to write a book, the initial idea was much more modest—at least from a publisher’s point of view. I wanted to write a book about black aesthetics and the internet. I wanted to write about the internet as this super, super black place in terms of vernacular, culture, visuals and circulation, for better or worse. It wasn’t until working with my agent and editor that we decided the book should be about post-millennium culture at-large, not just digital culture.

Khanya Mtshali: One of the central themes of the book is the idea that when we’re talking about appropriation, what we’re actually talking about is power. Why was that so important for you to emphasise?

Lauren Michele Jackson: When appropriation turned into a buzzword, it got conflated with forms of cultural borrowing that we didn’t like, when really, appropriation happens all the time. We all do it, we’re all involved in it, we’re all picking up and transmitting things that get repurposed on other people’s bodies and other people’s language, art, music … The example I use in my book is about rap music and hip-hop culture. While it’s a global phenomenon, even in its black American or American iteration, it needed cross-pollination and appropriation to exist. It needed appropriation across cultures of blackness, not just from coast to coast but it also needed contributions from black immigrants and Latinx immigrants. Appropriation is not in and of itself a bad thing, but the way it’s invoked in the culture makes it seem like it is. I wanted to delineate what I thought was under-critiqued, which is a perceived imbalance of power. When we’re upset about Miley Cyrus twerking on stage at the VMAs, we’re not so much upset that this black cultural form can circulate or have legs. We’re upset that this white pop star is going to get some credibility, profit or cultural cachet off of it. She gets to be edgy and push the envelope in a way that black women who twerk don’t. Instead they get all the negative things that stick to black people when they express themselves.

Khanya Mtshali: As someone who still yearns for pop music from the two-thousands, it was a thrill to read the first essay of the book, ‘The Pop Star: Swinging and Singing’, which explores the varying degrees to which white pop stars co-opted, and in some cases devoured, black aesthetics and musical traditions. I appreciated the focus on Christina Aguilera, whose career trajectory and position as a white Latina deeply influenced by black female musicianship has been fairly overlooked in music criticism. How did you end up selecting her as a case study? I imagine there must have been other white pop stars who would have made for equally interesting subjects.

Lauren Michele Jackson: I don’t remember when I made the decision that Christina Aguilera would be my case subject, but I did think she was a good choice for a lot of reasons. For one, I too very much love that early-two-thousands, late-nineties moment, on the verge of fetishism! I was a preteen, almost teenager during that era so it was very formative for me in terms of my musical tastes, my love of pop culture and all of that. I can still remember vividly, but not too vividly, the moment when Christina Aguilera did her ‘Dirrty’ thing and when that was a big deal. It was fun to go back and read the interviews and profiles. I started to notice things about that area of her career that I wasn’t too cognizant of when I was eleven or whatever. She’s also one of those people who’s had, relatively speaking, a long career. In some ways, she had this clichéd arc as the pop star, who became the naughty girl, who then mellowed out to become the vocalist. I did end up writing a little bit about Miley Cyrus’s arc in that chapter as well, but I don’t think I could have done an entire chapter about her or the Kardashians, for example. Christina Aguilera gave me the opportunity to step back from the ‘essay industrial complex’ of it all, and write an original story of her career through my interest in racial aesthetics. She has this interesting dimension to her where she is Latina and she identifies that way, but she’s also leveraged that same identity to preserve a sense of exoticism in the American imagination.

Khanya Mtshali: The title of the book comes from the writer Norman Mailer’s 1957 essay ‘The White Negro’, published in Dissent Magazine. It describes how the near destruction of the planet during World War II compelled a certain type of white man to flock to black urban enclaves where he would supposedly adopt the black man’s codes to live more immediately with death. When I first read the piece at university, I found it frustrating and offensive, especially when Mailer got real pseudo-race science-y about black male sexuality. But he does provide a timeless diagnosis of bohemian white Americans who use black aesthetics as a way to break ties with their safe, suburban values. You discuss the exploits of the contemporary white negro in the form of those yearly lists in which white writers take it upon themselves to ‘ban’ words founded in mostly black contexts. Mailer’s white negro seemed to be driven to black culture by existential reasons, but the contemporary white negro seems to be driven to black culture by boredom, which seems not as intense, high-stakes or ‘deep’. What do you make of that?

Lauren Michele Jackson: I don’t think boredom is necessarily benign or a boring mode of living. Boredom can lead to a lot of destructive forces. Boredom can be an existential crisis or an identity crisis because you’re asking yourself—who are you and what is your place in the world. Boredom can be powerful. I can understand the desire to symptomatically read some sort of deeper crisis here, but I think boredom is enough. It’s not like all of these white kids are self-consciously refashioning or making themselves into something else. That’s part of what I mean when I say most appropriation happens without people realising it. And by the time they do, it’s belated. You don’t notice the appropriative act, you just notice the aftermath. So I think part of it is boredom and part of it is the churn of online culture. I also think appropriation involves looking for something new. There’s a long established tradition of white artists looking to ‘the ethnics’ for newness and inspiration for their work, and I think that happens in a much more banal sense for the average white American.

Khanya Mtshali: You cover a lot of internet history, which I presume must have been difficult given how quickly things move online and how quickly problematic ‘receipts’ get deleted and erased. Could you walk us through your process? Did you encounter any difficulties with finding and archiving material?

Lauren Michele Jackson: So, I archive like crazy. If I see anything that’s related to something I’ve thought about or researched, I’ll save the link or I’ll download the picture or screenshot it then save it in a folder. I might not look at it for months or ever again, but at least I have it and I have the record there. The internet does move really fast and people delete things all the time, or they change their accounts, get suspended or banned—especially within the whims of Twitter. As soon as I started the book, I created a bunch of folders for different chapters and I’d just dump stuff in there for when I needed it. For me, it’s all about archiving, but there’s also a point where you have to let your memory be the guide. The internet is also ‘coveraged’ now because publications have realised the things that happen on Twitter, for example, are of note. It makes things a little bit easier because you have places like The Guardian that are talking about #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen or something like that. Using that you can recall the course of things, but you also can’t just rely on media outlets, because there are certain ways the story gets told that can ignore the messier part of events. Altogether, it’s about having screenshots and keeping a record of things.

Khanya Mtshali: In the Introduction, you mention Langston Hughes’s ‘Note on Commercial Theatre’ (1940), in which he expresses concern over the presence of black art without any black people. This was in contrast to what he had seen in the nineteen-twenties during the Harlem Renaissance. In a similar vein, someone on my timeline tweeted it was unnerving how everyone on Twitter sounded black American. It got me thinking about whether black people who experience localised American imperialism are ever given the chance to mourn and grieve the theft of their artistry and genius for profit. Is this even possible, given how relentless and longstanding appropriation of black cultural production is in America?

Lauren Michele Jackson: Well, I think the Hughes poem is a form of mourning and that tweet [you mentioned] is a form of mourning. When people throw up their hands and say, man, that sucks—I guess that’s a form of mourning too. I think mourning can look like a lot of different things because appropriation has become this always-happening thing that there’s not going to be this specific moment where we all sit and mourn the way black culture has been appropriated. The very fact that black culture changes and moves so rapidly is a de facto acknowledgement of the conditions in which it survives, because it’s constantly surveilled and looked at. Even if you think of something like Sterling Stuckey’s Slave Culture: Nationalist Theory and the Foundations of Black America, a book published in the nineteen-eighties that looks at plantation culture and the ways in which culture mutated on a plantation. There are old traditions and documents that reveal how black people express themselves. I think mourning happens in an everyday space. I don’t think it has to be ceremonial.

Khanya Mtshali: The essay on food was particularly interesting to me because there are people who might disapprove of cultural appropriation except when it happens in the culinary arts. You write about the former Food Network star Paula Deen, describing her as ‘white Mammy, plumping America one fried delicacy at a time’. I had never thought of her that way. At the height of her popularity, you could argue that Deen was the safest Mammy, whom white liberals nostalgic for a sanitised version of the South and Southern cuisine could openly and enthusiastically love. Could you explain the concept of a white Mammy to a non-American audience, who might interpret that as an oxymoron?

Lauren Michele Jackson: If you think about the characterological history of Mammy, she’s comforting, she’s desexed, she has a large bosom for you to wrap her arms around. If you think about Mammy, you get the picture of how a black woman is presented in the American imagination. I plan to write about this in my next book but if you think about Mammy moving from a figure on the American plantation to now, Mammy is still a black American woman but increasingly, she’s also a black immigrant woman. I think that’s interesting to think about. It may not have a lot to do with Paula Deen, but Paula Deen is Mammy in whiteface. She gave America what it wants from Mammy, but she also got to be very rich from being Mammy.

Khanya Mtshali: There was a not-so-distant time where social media appeared to be a place where black activism could flourish. In the penultimate essay of the book, you give a rundown of social media activism and consciousness raising, mentioning the beloved site Tumblr where so many of us went for our early political education; the DIY blogs started by black female writers, activists and scholars; the hashtag movements like Black Lives Matter. You even found time to fit in #Kony2012. Eventually this leads to the Trump presidency. In my view, you produce the most damning description of the so-called Resistance that emerged after his election in 2016: ‘Anger, too, experienced a makeover. The most racialised emotion in American history was suddenly cool.’ How is it that even negative stereotypes of black people, such as the Mammy or angry black person, can be appropriated by white people? That seems so outrageous.

Lauren Michele Jackson: Jonathan Metzl, a professor of sociology and psychiatry at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, wrote this book that was really impactful to me, called The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease (it’s also worth checking out his most recent book, Dying of Whiteness). In that book, he essentially looks at how the cultural and medical understanding of schizophrenia, which used to be a condition associated with affluent white women, was considered very benign until it coincided with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement, when the condition became acquired by black men. At that point, it adopted the negative characteristics associated with black protest. In fact, the title of the book, The Protest Psychosis, takes its name from a published research study that actually called schizophrenia the ‘protest psychosis’.

So one of the takeaways from that book is thinking about the racialisation of anger from the time of the plantation, where the idea of fighting for freedom and running away becomes a malady in terms of what was supposedly wrong with the brains of enslaved persons wanting to fight against their masters. You can trace from there how certain forms of black expression and energy were pathologised in medical and cultural discourse. Anger was not something that was a white ideal until post-Trump election, where all of a sudden, it’s cool to be angry. It wasn’t cool to be angry when Obama was president because the argument was, ‘What do you have to be angry about?’ The idea is that if Hillary [Clinton] got elected, we’d still be going to brunch. We wouldn’t be angry, but now we’re angry. Anger is the most racialised emotion in American history and it has always been the pathology of blackness in America. It’s kind of wild how the pendulum swings at the whims of a certain affluent white liberal class.

Khanya Mtshali: Thank you for your time.

- Khanya Mtshali is a writer and critic based in Johannesburg. Follow her on Twitter.

2 thoughts on “[Conversation Issue] ‘Appropriation is not in and of itself a bad thing, but the way it’s invoked in the culture makes it seem like it is’—Lauren Michele Jackson talks to Khanya Mtshali about her book, White Negroes”