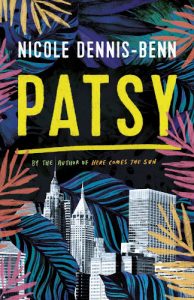

A novel of feminist radicalism, readable in the best sense of the word—Wamuwi Mbao reviews Patsy by Nicole Dennis-Benn, who will be at the Open Book Festival in Cape Town in September.

Patsy

Nicole Dennis-Benn

Oneworld, 2019

It may happen that when our descendants look back at our attempts to control, restrict and prevent the movement of our fellows between spaces, they will regard our ever-intensifying current efforts with the bemusement we reserve for the wrong-headed segregationists and imbecilic apartheid-ists of the twentieth century. How could they have got it so wrong, they might say?

More likely, they will have evolved newer and more complex methods of border policing and restriction that will be vaulted with greater determination by those whose imaginations propel them towards what they hope will be a better life. We will undoubtedly see more and more fiction that addresses the plight of the undocumented (a calumny we use to talk about those whose documents we deem not good enough for entry), and the vexing problems of immigration and inequality. The best of these works will be the ones that engage with the fullness of what it means to be a person in such a world.

On the strength of Nicole Dennis-Benn’s novel Patsy, that future literature will be full-bodied indeed. The Jamaican-born author’s sizeable second book is a large-canvas novel suffused with many of the same concerns that occupy her debut, the engrossing Here Comes the Sun, published in 2016. Dennis-Benn’s interest is in the torsions of society, and what stands out in both books is her deep moral commitment to the characters whose stories she is telling. For Dennis-Benn, to be human is to be capable of great love and truly awful behaviour. She finds reserves of truth in characters whose contradictions and ambiguities make them authentic.

Take Margot, the main character in Here Comes the Sun, who works in a hotel and dreams of becoming a manager and living with her lesbian lover away from the judgemental gaze of the community. Margot has sex with male guests to supplement her meagre income. She imagines that the unlikeable things she does will protect her sister Thandi from the harshness of the world. But her ambition sets into place a series of actions that culminate in Thandi entering the prostitution ring Margot has created, with the help of her corrupt, ‘high yellow’ benefactor. The novel poses questions about love and betrayal in a society whose impoverishments and brutalities throttle and choke all prospects of freedom.

The titular character of Patsy is a young Jamaican woman who struggles to keep her head above water. She provides for her daughter Tru, who is five when we meet her, as well as for her Bible-bashing mother, who does no work at all. Patsy is trying to find a way out of the suffocating poverty of Jamaica, and like many on the island, she dreams of winging her way to America and to opportunity. She is estranged from Tru’s father Roy, and though it would make life easier, she refuses to accept money from Pope, the neighbourhood kingpin.

Motivating her desire for escape further is Cicely, Patsy’s childhood friend and the love of her life, who has escaped to America, and who writes Patsy emotional letters filled with longing:

America is everything that we dreamed about. There is so much here. It’s cold and snows a lot in winter … I always pretend that you’re here too. I like to imagine us, free without your mother, my aunt, Pope, Roy, and everyone else in Pennyfield. Like I said, don’t tell a soul you heard from me. Now that I am here, my memory of you and our special friendship will live forever. You have always been my home in this world.

Patsy, who took the rap for helping Cicely cheat on a crucial maths exam, has aided her friend’s passage to better things. Cicely gets away with it because the teachers are more ready to believe that the beautiful, light-skinned girl is innocent. Patsy’s bright future is ruined. Now, years later, she pines for her friend while being deeply conscious that there is no possibility of their being together in a country where homophobia is so deeply ingrained. She has sex with an older insurance broker, who gives her the money to vouchsafe her way to America. Cicely, who has married a green-card-bearing man for the expediency of it, promises her a place to stay and a springboard into the American way of life.

Patsy is as complex a character as Margot, if less priggish and more hesitant in her self-realisation. She is aware that her life is one of thankless sacrifice, and she yearns to break away from the bonds that tie her to an environment that is unwelcoming and embittering. If that means breaking away from a status as mother that was undesired to the core, then so be it. As with Dennis-Benn’s first novel, Patsy thinks through how an oppressive social structure straitjackets those who live in it. Here, Patsy has to negotiate what it would mean to leave Tru behind: is she a bad mother for wanting her own happiness?

The question is left hanging as Patsy obtains a visa and leaves her daughter and her old life behind. Tru is sent to live with Roy, an overburdened policeman whose wife Marva has always wanted a daughter. From here, the stories of mother and daughter cleave apart, and we switch between Patsy’s and Tru’s divergent stories as each makes her own way in the world. The novel suspends us in the lurching chasm of their separation, as each painfully adjusts to her new life.

For Patsy, the beckoning promise of fulfilment makes the sacrifice worthwhile. However, the Cicely she finds waiting for her in America is ‘dressed in a manner as close to Scarlett O’Hara as Patsy has ever seen anyone pull off in real life’, and her mannerisms and way of speaking signal to us that America will not be the promised land. Patsy’s rising dismay crescendos when she realises that Cicely’s husband Marcus is a villainous brute for whom she is little more than a trophy. Patsy finds the situation untenable, and after witnessing Marcus beating Cicely, she begs her friend to leave the marriage and fulfil her fantasy. Cicely rebuffs her, telling Patsy that what they had belongs to the past and that she is unwilling to sever her lifeline for the speculative prospect of happiness with Patsy.

The story from here onwards is created by the progressive unlayering of historical violence. Patsy finds herself caught in the bind that traps many illegal immigrants, where going back means failure and humiliation, but staying means remaining in a treacly purgatory of menial jobs and alienation. She is lost in an America whose promises wash into a banal monotony of cheap fast food and inconsequential couplings devoid of emotion. Patsy learns soon enough that it isn’t enough simply to yearn for connection, and that being in America involves unimaginable sacrifice. Her co-worker and fellow immigrant Fionna tells her ‘we have to protect we self, an’ love small’, and the words resound throughout the novel. For Patsy, whose presence in the country is the result of a massive emotional gesture, loving small seems like the death of hope.

As Patsy struggles to find some sense of emotional order in her new life, the novel leans heavily on its dramaturgical furniture. We watch Patsy sink to lower and lower ebbs, and we expect that someone will finally arrive to love Patsy in the ways she needs to be loved. Someone does. We expect that Cicely will pop up again, and she does. Here, the author invests far too heavily in the foreshadow–flashback device, and I found myself just wishing the novel would get on with it and tell us what terrible and violent things bound Patsy and Cicely together.

Adding to the frustration is that the many moments of wonderful writing—a morning is ‘a merriment of blues, greens, and yellows’, the houses of Pennyfield are ‘weighted down by poverty and Mother Nature’, a look is described as ‘hidden and selfish, the way hagglers, men with erections, and loan sharks look at you’—share space with much weaker passages, and the latter begin to grate. Too often, the novel fails to resist making punctual appointments with the obvious, as in the following scene:

Patsy and Cicely take a seat on the padded chairs. There is a television mounted on a wall, playing the news on mute. President Bill Clinton is on the TV, talking to a journalist who seems to be challenging him on something. A photograph of a dark-haired woman keeps coming up, as do the words Case for Impeachment flashing across the screen as breaking news.

We know what purpose it serves (establishing a time and a national mood), but it is leaden exposition that betrays an authorial anxiety that would have been alleviated by placing greater faith in more prose carrying Patsy and Tru’s points of view. They are rendered strongly enough that they don’t require the heavy smudge of the context brush.

My sense that Dennis-Benn is a better writer than the low points in her novel reveals is heightened by the interleaving chapters that plot Tru’s growth toward adulthood. By comparison with her mother, Tru is an emotionally uninteresting character (story arcs in which children experience childhood as misery and self-awakening are tedious), but her love for the mother, who has chosen her own freedom over the relentless and demanding love of the child she did not want, creates the novel’s most resonant moment of psychological complexity. Tru spurns the affections of Roy’s much-put-upon wife, but flourishes under the watchful eye of her father, who allows her to be herself even when that self diverges from traditional expectations of how a girl should style or conduct herself.

The weave of the two narratives sometimes threatens to stretch its yarn, but the overall effect is a kinetic energy that impels the story forward with admirable pep. Sustaining that energy over the course of 420-odd pages was always going to be difficult, but Patsy almost accomplishes the feat. Tru’s story, particularly, is elastic enough to skip over some of the holes in the plot structure. And if the relationship between her and the cool girl from the rich side of town feels a little laboured, it is no less endearing for that.

Naturally, there is a moment of crisis for Tru, but it dissolves rather half-heartedly, almost as Dennis-Benn was afraid to steal the thunder from Patsy’s story. While her daughter’s story plays second fiddle to the cacophony that is Patsy’s emotional world, when we return to America, the long-promised grand reveal is also curiously muted. Patsy, whose lover has graciously and unrealistically let her go so that she can resolve her feelings, finds that her love for Cicely is now a thing of the past, freeing her up to love fully and vividly and expansively. The implication that this love will heal Patsy makes the climax feel as though it’s imported from a romance film.

The sense that the ending was rushed is only heightened by the final chapter, which shoves us hastily into the future, with an unsatisfyingly hurried scene that shows Tru as a successful athlete, well on her way to success, and every other narrative loose-end (of which there are rather too many) neatly cauterised. It feels like the sort of ending you’d write if the publisher demanded the manuscript two weeks before you were ready to turn it over, and it does the more careful work of previous chapters a disservice.

Its flaws notwithstanding, to be sure, this is a book whose affective force outstrips its technical sophistication. It feels compelling in its density, and while it rushes too eagerly towards the consolation of a tidy ending, it doesn’t ignore the social realities in which that ending takes place. To call a book ‘readable’ often sounds like ill-disguised damning with faint praise, but Patsy is readable in the best sense of the word. The feminist radicalism running through it carries the day, and the novel plays to its author’s capacity for drawing the world in prose whose honesty seems deeply necessary today.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.