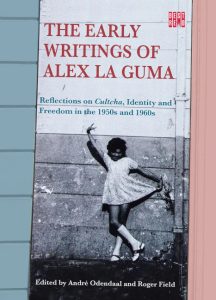

The JRB presents an excerpt from The Early Writings of Alex La Guma: Reflections on Cultcha, Identity and Freedom in the 1950s and 1960s.

The Early Writings of Alex La Guma: Reflections on Cultcha, Identity and Freedom in the 1950s and 1960s

Edited by André Odendaal and Roger Field

HSRC Press, 2025

The City of Gold

Long ago it was all rolling land which grim, stern, bearded men guarded with long guns and narrow-minded bigotry. They guarded the land from the people from whom they had taken it. They lived in isolation, one from the other, and their minds grew stunted and warped and murky with the disease of racial prejudice, until mental anaemia saw only white and the black was to be feared as a little child fears the dark.

Then one day a man walking in the long fields came across a stone. It was soft as lead and dull yellow. This stone could be smelted, refined, processed and turned into the shiny metal which crowns were made of. And then the people knew that wealth lay beneath the brown earth. And then men came with spades and pans and tools to tear up the land and wrench the richness from its bowels. They fought and cursed and killed for wealth below the green grass. They built shanties and sunk shafts. They poured in from all horizons. They built a roaring, roistering town, and called it Johannesburg.

But greed is a disease that gnaws at the vitals and eats at the soul. It spreads like mould and its remedy is its satisfaction. Foreign men coveted the richness of the Transvaal and the stern, bearded men took their rifles down from the walls and their long columns rode out to fight the invaders. They lost because they were overpowered by superior numbers and their own bigotry. And thereafter the gold was owned by strange men who sat in clamouring offices and watched long ribbons of paper winding out of their clicking machines. Far across the seas, the gold became tiny numbers which increased or diminished. The owners of the gold did not dig it from the ground, they did not hear the sharp sound of a pick striking rock or hear the clatter of pneumatic drills. They did not feel the sweat dripping from the brow or the hurt of strained muscles, the hard horniness of calloused palms.

Chinese were brought to dig the gold, and when they could not do it, the black men were torn from families, wives, children and the ripe land to dig down into the darkness to find the yellow metal. They sweated and died and created mountains where once the land had been green and virgin. And around the man-made mountains the shanties dropped away, and in their place grew a jungle of granite and steel and chromium. The mud paths became boulevards and macadam roads. The swaggering miners of old were replaced by new swarms of harassed, worried people, fenced in by stone and concrete and all forms of oppression. Alongside the mines new industries grew up and the army of workers grew in numbers and absorbed the atmosphere of strength. And the workers were dark-skinned in the main, and the rulers of them feared them, and made laws to bind and pinion their strength.

Today the mark of racialism, oppression and brutality lies like a hideous birthmark on the face of Johannesburg. It is seen in the slums and locations, the bulldozed stretches of the Western Areas, the jam-packed gaols and the police with pistols and Sten guns.

It is seen in hunger and rags, site and service, gangsterism and rioting. You can tramp the miles of streets and see no place to quench your thirst or appease your hunger. The bright signs reflect the rule of white supremacy. Bar-B-que, 20th Century Fox, Giacomino, Palace Beer Hall, Woodpecker Inn.

The Flying Squad hurtles past, dodging the all-white buses. At the railway stations the cops stand by to demand passes. Black men walk in fear.

But every coin has its reverse. Beauty is found even in a swamp. And the beauty is in the determination of the people. Beauty is in the long line of bus-boycotters, the roar at a meeting of a people who no longer wish to be slaves. There is beauty in the coffee stalls where you can buy a cup of steaming hot brew and two delicious fat-cakes for a sixpence, and chat idly with the friendly man behind the counter.

There is a richness greater than gold in the penny-whistle man walking easily along Pritchard Street, playing his lively tunes. There is a wealth untold in the welcome given by a working family in Vrededorp, the cups of tea and the factory-made biscuits; the at-home in the location where the can of beer is passed from hand to hand, mouth to mouth. There is beauty, too, in the welcoming smile of the shebeen queen, for the shebeen has become a place of relaxation, the local pub where pleasantries are exchanged and the chatter is quiet and meaningless.

Beneath the stony facade of the City of Gold there is a song which singing cannot express. There is a cheerfulness that laughter cannot satisfy, a tragedy that tears cannot obliterate. There is a vision that freedom will make as real as the sweat and the agony and the gold which is its heart.

The real wealth of the golden city, New Age, 25 April 1957

~~~

Publisher information

Alex la Guma was a major twentieth-century South African novelist. His first novel, A Walk in the Night, in 1966 brought him instant recognition as a pioneering writer on the African continent. Its ‘startling realism and accurate imagery’ drew high praise from his contemporaries, Wole Soyinka, later awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. The critic and writer, Lewis Nkosi, likewise, compared La Guma’s intense and sombre vision of the individual in society to that of Dostoevsky.

La Guma was also an important political figure. As leader of the South African Coloured People’s Organisation and a communist, he was charged with reason, banned, house arrested and eventually forced into exile. At the time of his death in 1985 he was serving as chief representative of the African National Congress in the Caribbean.

Published on the centenary of Alex LaGuma’s birth, on 20 February 1925, The Early Writings of Alex LaGuma contains a selection of his early work as a journalist and short story writer, before he became a published novelist and was forced into exile. It provides unique cameos of South African life and politics during turbulent time in the country’s history—the late 1950s and early 1960s, the years around Sharpeville—at the same time giving us insight into the making of a novelist.

The ‘hidden’ world of Alex La Guma—material, social, emotional, political and intellectual—at a time when he was developing into a serious writer, is revealed. Many of the themes in his fiction are first encountered and developed in these early newspaper articles, providing useful material for literary scholars seeking to understand the progression of his work.