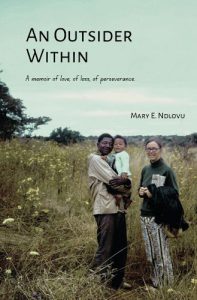

Percy Zvomuya reviews Mary E Ndlovu’s memoir, An Outsider Within: A Memoir of Love, of Loss, of Perseverance.

An Outsider Within: A Memoir of Love, of Loss, of Perseverance

Mary E Ndlovu

Weaver Press, 2024

The Canadian educator and historian Mary E Ndlovu spent fifty years in Africa. She arrived in newly independent Zambia in 1966, moved to Zimbabwe, her husband Edward’s home country, in 1980, and returned to Canada in 2016. The years she spent in Africa—1966 to 2016, a total of five decades—have a nice symmetry to them, and yet that period was anything but one of harmony and equilibrium.

It was instead an era of tectonic turbulence, when Zambia, then Northern Rhodesia, not only drifted from the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, together with its southern neighbour, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and Nyasaland (Malawi) in 1963, but also, the following year, broke away from the ‘mother’ country, Britain. As an independent country, led by the charismatic Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia staked its place in the commonwealth of free nations; it would help its neighbours in the region—Southern Rhodesia, Angola, South West Africa (Namibia) and South Africa—also get their freedom.

Mary Krug had been a postgraduate student of Columbia University’s Russian Institute when she lost interest in her studies. She used to attend lectures given by the ‘dashing’ Polish American scholar Zbigniew Brzezinski; but not even his good looks were enough to maintain her passion for her education. ‘Who cared, after all, what happened during Catherine the Great’s Reign?’ she writes in her just-released memoir An Outsider Within: A Memoir of Love, of Loss, of Perseverance. By chance she bumped into an idealistic compatriot who had spent time in India. The ‘Third World’, her compatriot advised, was the place to be, where one could learn ‘about the reality of material poverty’ and be ‘a part of change that could affect so many people’s lives’.

Krug soon applied to Canadian University Service Overseas (CUSO), a non-governmental organisation involved in sending young Canadians to the developing world; she got a two-year contract, and was posted to Chipembi Girls Secondary School, Zambia’s pre-eminent girls’ school, an hour away from Lusaka. Although near the Zambian capital, the school was in the proverbial sticks. Electricity was available, but only for four hours per day. The school had few of the middle class comforts she had been used to back home. ‘How would I ever survive that long? What had I done? Was I wasting my life?’ she asked herself.

Although one of the stated justifications for colonising Africa was to spread Western civilisation, educating Africans was never a concern for the Northern Rhodesian administration. It was, in fact, an afterthought. It’s thus not surprising that Chipembi was run by the Wesleyan Methodist Church, as many other places Africans went to school were established and run by the Catholic Church, the Presbyterians and other congregations. So dire was the situation that at independence in 1964, only 1000 Zambians had Ordinary Level passes and just 100 boasted a university qualification.

Krug was teaching history, among other subjects, but she found it hard to connect with her pupils. The history curriculum—Roman history, nineteenth century British history—never came alive to her listless students, divorced as it was from their immediate realities. The girls approached Ms Krug: we want to be taught our history. She took the appeal to the head mistress, a missionary from England. No, she demurred. ‘“Teaching African history would be dangerous as the girls would get emotionally involved”—which of course was exactly my point.’ Fortunately, the syllabus was Africanised not long afterwards by government decree.

Krug was a misfit at Chipembi. Her liberal, atheist outlook didn’t chime with this missionary, late-colonial community. She wanted out. Fortunately, she was able to get a position as a research assistant at the newly established University of Zambia in the capital. The British, who were not willing to build primary and secondary schools, were never going to bother with a tertiary institution, so we should not be startled that Northern Rhodesia never previously had a university of its own. The University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (now University of Zimbabwe) had been built in the mid nineteen-fifties in Salisbury (now Harare), during the days of the federation. As the three territories were technically one country, Northern Rhodesians could of course enrol at that institution. But when the federation dissolved in 1963, Southern Rhodesia became the primary beneficiary.

From the monotony of the missionary enclave of Chipembi, Krug was ‘catapulted into a cacophony of cultures and nationalities that were laying the foundations for the new Zambia’. Lecturers from Britain, the United States, Canada and independent Asian countries were some of her colleagues; also in that cohort were teachers from South Africa and (Southern) Rhodesia. While the students were mostly Zambian, a significant group were black Rhodesians—the name ‘Zimbabweans’ had not yet quite caught on.

~~~

On 25 May 1968, Krug was invited to an Africa Day party. Africa Day then was recently minted, the occasion when the Ghanaian leader Kwame Nkrumah, the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, the Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, and other African leaders had signed the paper that gave birth to the Organisation of African Unity, as the precursor to today’s African Union was known. Present at the gathering was Edward Ndlovu, a tall black Rhodesian—a ‘not very handsome African man’. Naturally, Edward didn’t like the British, who had occupied his native land since 1890, nor Americans, the new imperialists, but he could make exceptions for Canadians. They chatted for a while and then Krug left to go home with a compatriot. Although it was May, long past the rainy season, there was a violent thunderstorm: ‘In Africa rain tends to be a good omen, something I was unaware of at the time.’

Edward found a reason to turn up at Krug’s office. He arrived with a file of documents, written in French, and asked her, as she was Canadian, whether she could translate them for him. There were letters from Algeria, then led by Houari Boumédiène, in which Zimbabwean nationalists were being invited to the country for certain meetings. The Canadian was intrigued. She had never met a Zimbabwean freedom fighter before. She had been immersed in Soviet history, however, and so had some context when it came to revolutions: ‘It might be interesting to learn more about this man and his politics,’ Krug thought.

Edward Ndlovu, of mixed Ndebele and Sotho heritage, was an executive of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu). Together with the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu), then led by Ndabaningi Sithole, Zapu was one of Rhodesia’s main nationalist parties. Zapu’s leader, Joshua Nkomo, was in detention in Gonakudzingwa, on the country’s south-east border with Mozambique. Edward should also have been a detainee in the penal colony, but had been in Lusaka when Nkomo and others were arrested.

At that point, Edward had already lived in Accra, Ghana, and Cairo, Egypt, as Zapu’s representative, and had travelled quite extensively. Although he had no university education, his knowledge of the world drew a portrait of a sophisticated man. But whatever the two had started between them was circumscribed by forces beyond their control. She was a white woman, and he was involved in a struggle against an apartheid system presided over by Edward’s white compatriots: how would it look to his colleagues in Zapu if he were to turn up at a party with a white woman? And there were spies everywhere: Rhodesian, British, American and Soviet. As if he were a spy himself, Edward had the habit of disappearing, and then, as suddenly, appearing again.

In 1968, Krug’s contract with CUSO came to an end and she had to make decisions—not just about her career, but also about a life partner. It wasn’t just Edward who was in the romantic picture, but also an Austrian called Peter. Despite the obvious difficulties of interracial love in a time of race war, and Edward’s crazy itinerary as he courted allies and friends, and worked to conjure up diplomatic and material support for Zapu, it was Edward ‘whom I was falling in love with!’ Back again in Toronto, Canada, Krug enrolled for a teaching qualification. Just as well, as she would soon return to the University of Zambia as a lecturer.

But in Africa, trouble was afoot. There had been a ‘rebellion’ within Zapu, during which a band of guerrillas had attempted to capture the party’s leadership in exile. Edward happened not to be at the party headquarters, Zimbabwe House, and was spared. Around this time, there was a split in Zapu, and some Shona members left. From wherever he was then, Edward wrote Mary a letter with a proposal of sorts: ‘You and me must settle down to decide definitely on our intentions.’ The nationalist also reminded the lecturer that his commitment was first to the struggle for his homeland.

It was once thought that this struggle would be quick (just like that of the Zambians and Malawians), and so Zapu comrades had agreed not to marry until Zimbabwe was free. But as the horizon of independence stretched out, and the racists of Rhodesia dug in, the no-spouse rule was deemed unrealistic. So Cde Edward would get married. Before the nuptials, Krug travelled to Bulawayo to meet Edward’s mother. It was a brief meeting in the ghetto of Barbourfields. From that day, the matriarch Gogo Ndlovu took to calling her ‘nkosikazi’—princess. Their marriage ceremony, officiated by Krug’s father, was in London, England. And Nkosikazi Ndlovu soon had a little princess of her own, Gugu, who transformed her life. Mrs Ndlovu was no longer just one human being; she felt fulfilled that, together with Edward, she had created ‘a new person’.

~~~

For a quite voluminous read (423 pages), Ndlovu’s book is scant on historical figures, and flooded with quotidian detail. These are my main complaints, as a history junkie. Granted, the book is a memoir, not an authoritative account of Zapu figures in exile; nor is it a biography of Edward Ndlovu. (I hope she is working on a biography of her husband; I can’t think of anyone better placed to write that book.) But the work’s structure and the years its author explores, 1966 to 2016, clearly mark it as a political tract of some kind—it covers, after all, her period as an engagée, or the spouse of an engagé.

Ndlovu doesn’t dedicate much time to the revered nationalist Jason Ziyaphapha Moyo, except to say that he didn’t like women in general, considering them a ‘problem’ (a nuisance?), and that he didn’t approve of her marriage to Edward, because, no doubt, she was white. Now Moyo, popularly known as ‘JZ’, is a very interesting personage in the annals of Zimbabwe’s history. He was Robert Mugabe’s best man at his first wedding, to Sally, for instance. But Moyo’s main cameo in this book is at his funeral. He had been blown up—the victim of a parcel bomb sent from Botswana. Mugabe travelled from his Maputo base to Lusaka to attend. By this time, Zanu and Zapu were estranged from each other, despite attempts by regional leaders to unify them, but there was no chance Mugabe wouldn’t have gone.

Ndlovu doesn’t include the details of the speeches by Nkomo, Zapu’s president, and Mugabe, except to say that she was ‘impressed by the clarity and conviction of his [Mugabe’s] words, spoken in English’. Mugabe’s speech was rather dry and workmanlike, but Nkomo’s is worth sharing in this piece.

First, to deliver a eulogy at the funeral on 29 January 1979, Nkomo evoked what most accounts suggest was a remarkable and disciplined life dedicated to struggle. ‘The party has lost a fighter. The country has lost a devoted son,’ Nkomo began. He then spoke about the instant when he received news of the death of Moyo: ‘At one moment I said we should return [from Iraq, where they were seeking support] instead of continuing to Belgrade.’ He had then phoned ‘my brother and comrade, President Kaunda’, but the Zambian leader could hardly speak from grief. ‘How serious it is when a man of President Kaunda’s status could fail even to talk because of this loss,’ Nkomo said. He then addressed his old friend, and now rival, in soapstone textures: ‘Here I have just received Comrade Robert Mugabe. There was a time when people thought it was unthinkable that Robert and all these young men could meet and embrace as we have just done. I call him by his first name because I have worked with this young man, Robert Mugabe. I know his heart.’ In a gesture of reconciliation, Moyo then alluded to the political differences between Zanu and Zapu and observed, ‘But if we can talk to [Ian] Smith, if we can talk to the British government who have murdered our people since 1890 to this very day, what of happenings that occur while we struggle for our country?’

Ndlovu is also stingy on the details of an intriguing US$1 million donation the party received from the Shah of Iran. Most of Zapu’s support had come from the Eastern Bloc—East Germany, Soviet Union and Cuba. When she quizzed her husband on the morality of accepting money from such a figure, Edward’s response ‘was that he would take money from the devil if it would help liberate Zimbabwe’. On receiving the devil’s money, Edward had suggested they draw a budget, but Nkomo dismissed this as unnecessary. Edward was also not ‘impressed by some of Nkomo’s personal behaviour on the trip,’ but what this entailed, we are left to guess.

~~~

The years between 1975 and the Lancaster House conference in 1979 were brutal. Smith had decided to make the Zambian government and people pay for their support of liberation movements. Rhodesia’s Hawker Hunter aeroplanes, which until then had bombed guerrilla targets on the Zambezi River frontier, began to fly into Zambian territory, where they would bomb camps and other targets. Zambians were often killed. It was not only JZ who died during this period but plenty of others, including, most notably, Alfred Nikita Mangena, a Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (Zipra) commander—a victim, some accounts say, of a landmine detonation.

In the middle of 1979, Zambia hosted the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM), where the idea of the Lancaster House conference was adopted. Present at the summit was Margaret Thatcher, who had become Britain’s prime minister in May. Her appointment came just a month after Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s election to become prime minister of a renegade state called Zimbabwe Rhodesia. It was a sham government: the prelate was in control only in name, real power being in the hands of Smith and his inner circle of hawks. Zimbabwe Rhodesia (Rhombabwe?) was rightly criticised (by much of Africa, the European Economic Community, and Jimmy Carter’s White House, among others) as Smith’s attempts to forestall genuine black majority rule.

Small wonder, then, that Thatcher came to Zambia in some trepidation. She had carried dark glasses to Lusaka and when asked why, she replied, ‘I am absolutely certain that when I land at Lusaka they are going to throw acid in my face.’ In the event, nothing of the sort happened, but from the deliberations at the Lusaka summit it was decided Britain would temporarily take over Rhodesia, and convene a constitutional conference at Lancaster House that would decide the fate of the colony.

In February 1980, as Ndlovu listened to the election results made possible by the Lancaster House conference—Zanu-PF had won with an overwhelming majority of 57 seats, PF-Zapu had 20, United African National Council only 3—she made what turned out to be a prescient observation: ‘There will be disaster in Matabeleland.’

The two southern provinces, Matabeleland South and North, are predominantly populated by the Ndebele ethnic group. In the 1980 election, the Ndebele had overwhelmingly voted for PF-Zapu. Most of Zanu-PF’s seats had come from the rest of the country, where the Shona language groups predominantly live:

Had the people voted on ethnic lines, benefiting Zanu who operated mainly in the areas of the majority Shona tribe? Had years of effort to divide the country on tribal lines by politicians both internal and external finally borne bitter fruit? Or was something more sinister afoot? Many were the stories that Edward brought when he finally returned to Lusaka—Zanu campaigners had warned voters that they could see them voting by looking through their gun sights; the British, who were managing the elections, had conveniently failed to rein in Zanu’s intimidation of voters by guerrillas and mujibhas (young people who were used as messengers and lookouts in the war) who had not signed in to the assembly points or others who had left them; the British wanted to prevent the Soviet-supported Zapu [the ANC’s allies] from gaining power so close to South Africa so they gave Zanu advantages; ballot boxes in areas loyal to Zapu disappeared as did Zapu campaigners. Together we debated whether these stories were probable. Some were probable, others not.

~~~

Edward Ndlovu was one of PF-Zapu’s twenty MPs. For the first time in their marriage, Edward had a salary slip. As the parliament was in Harare, over 400 kilometres away, this meant a regular commute to the capital. Mary Ndlovu soon got a job as lecturer at Hillside Teachers’ College, in Bulawayo, formerly a whites-only institution. These jobs opened up middle class possibilities for the family. The couple managed to buy a house on a fifteen-acre plot in Waterford, a previously whites-only suburb. As Rhodesians fled majority rule, mainly to resettle in South Africa, Australia and elsewhere, houses were put on the market cheaply. The Ndlovus took in some of Edward’s young nieces from rural Gwanda, a dry area to the south of Bulawayo, to give them the benefits of a good city education. In addition to their own daughters, Gugu and Zanele, and the last born, a son, Vulindlela, the house was filled with youthful energy from the Ndlovu extended clan.

If normality was creeping into the suburban Ndlovu household, the country at large was tearing at the seams. At hand to light the embers was the flame-throwing finance minister, Enos Nkala. He had gone down to Bulawayo to address rallies and continue his personal rivalry with his fellow cabinet colleague and home affairs minister, Nkomo. ‘Zapu had declared itself the enemy of Zanu-PF,’ he said. ‘If it means a few blows, we will deliver them.’ Soon, Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (Zanla) and Zipra guerrillas—reportedly 3 000 on each side—started exchanging fire involving AK-47 rifles, machine guns, grenades and rockets in a full-scale ghetto battle. The violence ensnared the people of Entumbane, a township in Bulawayo and Chitungwiza, near Harare.

In urging the two nationalist parties to unite, the Tanzanian leader Julius Nyerere had issued a warning in a story carried by the South African paper the Rand Daily Mail in 1979: ‘No liberation—no country—has had two armies. You can’t have a country with two armies.’ His forebodings, which, to be fair, were shared by Zimbabweans themselves, started coming to pass. There was ‘a grave danger from having two separate liberation armies, which could erupt into civil war in a free Zimbabwe,’ said Mugabe himself in March 1977.

The conflagration between the two armed groups was snuffed out by the Zimbabwe National Army and the Police Support Unit. The official figures state that fifty-eight people died and more than five hundred were injured, even though hundreds more are believed to have been killed. Quiet eventually returned for a couple of months, before the outbreak of Entumbane II, for another round of bloodletting.

What was happening was this: former Zipra guerrillas were deserting the new army, some to head to the bush as so-called ‘dissidents’, others to go home (as Edward’s young brother, Bethany, did), and some to go to South Africa. ‘There were armed deserters,’ Ndlovu writes:

Once when Edward was visiting his home [in Gwanda] without us he received a delegation from a group that was apparently camped in the hills nearby. They demanded that he come to their camp, which he did, in spite of the potential danger. However, they were friendly and simply asked him why the Zapu leadership was ignoring them and asked him to convey a message that they needed help. He had the impression that they were more desperate than anything else, and had put themselves in a position of no return, even though they did not really want to fight the government. The situation was clearly volatile. There were also rumours that some of these ‘dissidents’ were being sponsored by South Africa and receiving weapons from them.

That was the excuse Mugabe needed to constitute a new army unit, the infamous Fifth Brigade, commonly known as Gukurahundi. The brigade was trained by North Korean instructors and soon deployed to rural Matabeleland. The numbers of those killed in a campaign that ended only in 1987 is estimated to be 20 000 Ndebele civilians.

Edward was spared the worst of the excesses of those years but was repeatedly detained and even spent some time in Chikurubi maximum security prison, where he had shared a hospital bed with Zipra commander Lookout Mafela Masuku. (Edward was of delicate health. In the nineteen-seventies, he had a kidney transplant. He died of liver cancer in 1989. He was the first person from PF-Zapu to be buried at National Heroes Acre.) Masuku, together with Zipra military intelligence chief Dumiso Dabengwa, had been tried for treason and cleared, but was still detained by Mugabe under emergency powers. Edward was fortunate to have a wife who wielded a powerful passport. During his incarceration, the Canadian government pressured the Mugabe administration to release him.

~~~

Mary Ndlovu stayed at Hillside Teachers College until 1992, when she left to go and work in the legal non-governmental sector. Zimbabwe, like Zambia, was not well equipped to deal with freedom. At independence, according to the country’s first minister of education, Dzingai Mutumbuka, ‘more than half of the population is innumerate and illiterate’. In 1979, there were only 2 401 primary and 177 secondary schools in Southern Rhodesia. ‘As you can imagine, it’s not just a problem of reopening schools, it is a problem of expansion, expanding primary and secondary schools. It’s going to require massive staffing,’ Mutumbuka told the weekly newspaper Financial Gazette at the time.

Ndlovu had started off in the history department and was suddenly moved to education. The principal was under pressure from Mugabe’s government to expand the college’s capacity to train more and more teachers. The faculty taught modules that were compulsory for every student. Ndlovu had to familiarise herself with the new curriculum: a student by night, and a teacher by day. But the fall of educational standards was inevitable. It was impossible to expand at the dizzying rates required while also maintaining excellence. ‘Before long, pass rates on formal exams, at that time provided by English examining boards, dropped drastically,’ Ndlovu writes.

If there was an upside to being at the school, it was the excursions into nearby towns and rural areas. The instructors in the education department had to travel regularly to examine students who were on what was called ‘teaching practice’ (TP for short) in schools scattered mostly in the southern provinces. TP was an innovative instrument devised by the government to give the students hands-on experience, but also to help deal with staffing shortages in the new schools. The student teachers got a stipend, but had a fully qualified teacher’s responsibilities.

One of the students Ndlovu had to examine was Yvonne Vera, later to become a prize-winning author and the director of the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo. Ndlovu felt that, of all subjects, the English language was the most poorly taught, ‘as students mechanically worked their way through the comprehension exercises and questions in a standard text. The college English lecturers themselves did not like teaching language and all wanted to lecture on literature, which was hardly taught as a subject in these rural schools’. Then one day she saw Vera conducting a lesson. She started by placing a picture of an elderly man on the blackboard at the front of the classroom. She told the pupils to study the picture and then started asking them questions: ‘Describe his face, look at his eyes—what do they tell us about the old man—is he a chief? What is he thinking about? What kind of person is he?’ Ndlovu was known as a ‘mean’ marker but she didn’t hesitate to award the young Vera an ‘A’—the highest possible mark. It’s not certain whether Vera had started writing fiction then, but she was clearly already sharpening her keen observational nous, developing the powers of description she later put to use in her books: Why Don’t You Carve Other Animals, Nehanda, Without a Name, Under the Tongue, Butterfly Burning and The Stone Virgins.

~~~

‘Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful,’ the English novelist George Orwell wrote. ‘A man who gives a good account of himself is probably lying, since any life when viewed from the inside is simply a series of defeats.’ In An Outsider Within, Ndlovu has left out embarrassing details on Zapu and its leaders, treading rather carefully, and not mentioning names. Yet Orwell’s condition of what makes a good autobiography is stifling. The British biographer and literary critic Hermione Lee, by contrast, has written that when ‘we are reading other forms of life writing,’ be it memoir, autobiography or autobiographical fiction, etc, etc, ‘we are always drawn to moments of intimacy, revelation, or particular inwardness’.

An Outsider Within: A Memoir of Love, of Loss, of Perseverance, as the title suggests, meets Lee’s standard. In the fifty years she lived on the continent of Africa, Mary Ndlovu tried to understand Africans, not always with success. This included embracing Africa’s continent-wide refusal of the Western ‘nuclear family’ by taking in Edward’s clansmen and clanswomen and living with them long after her husband’s death. She could have upped and left for Canada, but she stayed on, in a country that was sliding into the well-rehearsed socioeconomic problems brought about by Mugabe’s mismanagement and the consequent International Monetary Fund prescriptions.

‘Should I have been more sympathetic? Should I have tried to understand and make an effort to accept a pre-scientific view of the world?’ Ndlovu writes, referring to a niece she raised, who later became a French teacher, and who believed in the tokoloshe—a type of goblin, a curious concept in African metaphysics. ‘If I rejected them did it mean that it was impossible for me to fully embrace the culture of my husband?’

An Outsider Within is a worthy addition to the Zimbabwean library of the struggle-engaged, which includes Re-living The Second Chimurenga by Fay Chung, the Zimbabwean nationalist of Chinese descent and former education minister; Through the Darkness by Judith Todd, the anti-racist activist, daughter of the New Zealand-born liberal couple and missionaries Garfield Todd and his wife Grace; and My Struggle, My Life, South African-born nurse Stella Nkolombe Madzimbamuto’s memoir of her engagement with the struggle for Zimbabwe. Ndlovu’s book may also be the final book that Zimbabwe’s storied imprint, Weaver Press, will publish, after operating from 1998 to late last year. It is a remarkable bookend to a quarter century of publishing.

- Percy Zvomuya is a writer, reader, publisher, tree planter, editor and selecta. His writing has appeared in the Mail & Guardian, The Guardian, Chimurenga, Al Jazeera, the London Review of Books blog and the Johannesburg Review of Books.