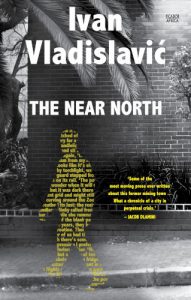

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from The Near North, the new book by Ivan Vladislavić, which will be published in March.

The Near North

Ivan Vladislavić

Picador Africa, 2024

In my last years in Troyeville, I stopped going to the old city centre and Hillbrow. I grew used to driving north to Killarney, Rosebank, Norwood and beyond in search of coffee, conversation and books, and forty minutes in the car, taking traffic into account, became the standard allowance for any trip. My crosstown move to Riviera caused the distances between familiar points to collapse. Now most of the places I needed to go were fifteen or twenty minutes away rather than thirty or forty. In my first year in the north, I always arrived at my destination a quarter of an hour early. I had to learn a new sense of distance and proximity.

I expected to find other senses disordered and they were. For thirty-five years, I had lived and worked mainly in the eastern suburbs of Joburg, and never lived north of Louis Botha Avenue. Among the dozen places I have called home, Riviera is the northernmost. For a long time after I came here, I had the sense that the city was behind me rather than in front, and often it still feels this way. Despite the fact that I long ago stopped going ‘downtown’ regularly, I still take my bearings from the inner city and Hillbrow; they still lie at the heart of my proprioceptive city.

Bringing the map and the territory together must register in the body like a sense of direction or balance. Typographers and printers use ‘registration marks’ on plates and transparencies, so that they ‘register’, or align properly, during printing, and walkers seem to rely on the sensory or psychic equivalents to locate themselves in the world. As a visitor in a foreign city, I have felt utterly bewildered when the direction of a journey through the streets does not match the orientation of the map or my intuited sense of where the city should lie in relation to my starting point. Must I turn around with the map in my hand, facing away from my intended destination, and imagine the route at my back? Or turn the map around in my hands, so that it matches the territory, and read the street names upside down?

The bodily sense of where you stand in relation to a place is deeply ingrained and mysterious. How does this sense develop? My childhood homes in Pretoria were mainly on the southern edges of the city: when we went to ‘town’, we went north. This chance alignment of my place in the real world and the northerly orientation of the city map may have ingrained a habit of mind and body that I cannot easily change. My internal compass needle points north. I prefer to face north when I am at my desk or on my balcony. From the vantage point of home, I like to have the city ‘in front’ of me, like text on a page or film on a screen. If I look south from the kitchen window of my flat, I see the top of the Hillbrow Tower, haloed in cool fluorescents as garish as an old-fashioned jukebox, sticking up above the yellow-brick hulk of Martinhall Manor. Familiar as it is, it pains me to look back on it. I wish to see it on the northern horizon from my lounge window on the opposite side of the flat.

What’s amusing about my disorientation is that many people now think of the old central business district as part of the south and have no desire to go there. The heart of Joburg has drifted north in the last fifty years, floating on slow economic currents or driven headlong on a torrent of political change and anxiety, and many, perhaps even most, Joburgers now think of Sandton (home of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, the most expensive square mile of real estate, the tallest hotel) as the city centre. Clive Chipkin’s designation of Sandton as CBD-2—he leaves the honour of CBD-1 where it belongs—is well known. Fact is, I can see the lights of the new office towers in Rosebank, which might lay claim to being CBD-3, from my writing desk. By some accounts, here in Riviera I might actually be in the middle of Joburg. Of course, everyone believes that their chosen location is ‘central’ and therefore convenient.

My move north revealed another surprising orientation. In Troyeville my house faced north, but venturing out mainly took me west or east: westwards into the city and beyond, to Brixton or Mayfair, and eastwards, down the length of Kensington, and out to the East Rand. My habitual walks ran along Roberts Avenue to the Darras Centre and back home on Kitchener; or along Commissioner into the city and back on Market; or up and down the avenues of Bez Valley. Wherever I lived in Joburg, I fell into walking this way: west on Kotze and east on Pretoria in Hillbrow; west on Collins and east on Caroline in Brixton; or west on Webb and east on Saunders in Yeoville.

It’s no great mystery. The deep currents of the city run east and west. The long, broken ridges that are the visible signs of the gold-bearing reef on which the city was founded made for roads as inevitable as rivers. Main Reef Road is our Danube. It is the lie of the land, the flow to go with. One-way streets channel the traffic this way too and driving might have shaped my walking habits.

Here in Riviera, I have had to reset this compass. Now my habitual walks run north and south, following the layout of the long streets in Houghton. The topography frustrates my efforts to walk on the eastwest axis. The blocks in Killarney are too short, and those in Saxonwold are irregular. When a suburb was laid out in the Sachsenwald, the planners were guided by forest tracks and natural features, and so the streets, unusually for this city, are not on a regular grid.

If I am driving, more often than not I follow the old beaten paths.

~~~

- Ivan Vladislavić is a Patron of The JRB. He has built a formidable reputation as an award-winning, critically acclaimed author of a significant body of literary work. Based in Johannesburg, he is a Distinguished Professor in Creative Writing at Wits University. He has won and been shortlisted for many of South Africa’s literary prizes, longlisted for the Frank O’Connor Short Story Prize, and shortlisted for the Ondaatje and Warwick Prizes. In 2015, he won the prestigious Windham–Campbell Prize. His books include the novels The Folly, The Restless Supermarket, The Exploded View, The Distance and Double Negative, as well as short story collections 101 Detectives and Flashback Hotel. In 2006, he published Portrait with Keys, a sequence of documentary texts on Johannesburg. Visit his website here.

~~~

Publisher information

The Near North is a vivid account of life in Johannesburg in times of crisis. From the stony ridges of Langermann Kop in Kensington to the tree-lined avenues of Houghton, we follow the writer through the city’s streets, meeting its ghosts and journeying through time and (often circumscribed) space, finding meaning in the everyday and incidental.

At once an echo of Ivan Vladislavić’s award-winning Portrait with Keys and an original work of intense acuity and quiet power, The Near North is both intimate and expansive, ranging from small domestic dramas to great public spectacles. Wryly playful at times, fiercely serious at others, it is certain to move and delight all who accompany the writer through its pages.

~~~