This is the fourth in a series of long-form interviews by Patron Makhosazana Xaba to be hosted on The JRB, which focus on contemporary collections by Black women and non-binary poets. The first, with Maneo Refiloe Mohale, can be found here, the second, with Katleho Kano Shoro, here, and the third, with Sarah Lubala, here. In opening up a space for wide-ranging, erudite and graceful conversations, Xaba aims to correct the misdeeds of the past by engaging black women and non-binary poets seriously on their ideas and on their work.

Two previous long-form interviews, with Mthunzikazi A Mbungwana on her isiXhosa volume Unam Wena, and with Athambile Masola on her debut collection Ilifa, were published in New Coin last year.

Makhosazana Xaba (MX): It has been a great joy being a witness to your journey in poetry. I remember so well how I first heard of you. Myesha Jenkins had attended the ‘No Camp Chairs Poetry Picnic’ session and she couldn’t stop talking about you. You pioneered this idea of a picnic, camping out and enjoying poetry in the garden facing the Union Buildings in Pretoria. Three questions: How did this idea come about? How would you summarise your experience of leading these fortnightly sessions? And what is the biggest lesson you learned?

vangile gantsho (vg): During a stint at the University of Pretoria, my friends, Nolindo and Noki Zibi, and I decided we wanted a poetry hangout. Something low maintenance and something that could feel like a jam session. So we started a jam session, On the Patch, in the middle of the student centre. These grew quite popular and eventually led to the Writers’ Forum.

When I left Tuks, I wanted something similar, and the Union Buildings felt like the perfect place. I enjoyed the political statement of what felt like a soapbox, and the democracy of not allowing camp chairs. It also felt like it would dispel the myth that poetry was elitist.

How would I summarise the experience? Some shining moments and some very painful reminders that poets are people and people are complicated. I enjoyed hosting and organising the picnics at first. I enjoyed preparing food and organising people to hold the space—so for example we had a picnic with Ebukhosini, where they were able to bring their poets and share their ideas on community and what a Pan-Afrikanist society would look like if we all had a better understanding of Afrikan histories and cosmologies. We would jam and learn from different groups and sometimes individual poets. It was fun. The space allowed me to meet fantastic poets: Mthunzikazi Mbungwana, David wa Maahlamela, the late Matete Motsoaledi …

It also gave me many tender moments: while waiting for everyone to arrive, I would often meet people who would share stories with me. I met a Congolese security guard who was an engineer back home, an unhoused vegetarian rasta intellectual from Cape Town who turned out to be from a well-off family, who I suspect, in hindsight, waye thwasa. I found out we had mutual friends. And I remember he had this map of Pangea, on the back of which he had written a whole book in the tiniest handwriting—lines and lines, I swear! Ibingathi zi notes ze political prisoners. I wonder what happened to him.

Then a few things began to happen. I got busier and, try as I may, I couldn’t get people to commit to the picnics without me. Tanya Pretorius and Yamkela Sigwili held it down for some time, but people love the idea of a person, not a movement. I wanted something that could stand on its own, people were drawn to the idea of me at the helm. Then the misogyny started seeping through. People became comfortable and the everyday violence of this capitalist patriarchal world began to come through. I felt triggered. It didn’t feel safe anymore. There was more ego than poetry and I became less and less willing to put my heart into it.

I learned that not everyone who comes to poetry comes to her for the same reasons. Or treats her with the same care. I learned that Gogo Toni (Morrison) was right: ‘Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence, does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge.’ Conversely, I was reminded that there are so many beautiful people in life. And poetry can offer us an entry point into each other’s hearts. I think those picnics, in some ways, prepared me for the writing healing workshops I do now. Where the end result is not always a masterpiece, rather a safe pouring out of self.

I also learned that I believe in picnics. Truly. I love them. I love the idea of sharing food and words and space and would love to have more of them.

MX: Men and their violence! No! No! No!

At the memorial for Bra Willie (Keorapetse Kgositsile) you received a standing ovation when you recited your poem ‘I expect more from you’. Because of this poem you were also kicked out of iShashalazi theatre festival. Please write a poem that captures the journey of this poem; a biography of this poem, starting from its conception.

vg:

this poem is a house i can no longer live inall her children are gone moved out forced onto the streets

and i am the grandmother who is infant and orphan

who is an indulgent selfish teenager eating bread she does not know the cost of

(or maybe she is crying because she can see they will never give her bread)

my knees remember the stoep where everyone gathered

those who felt unhoused felt as though the mountain had grown without them

felt forgotten by the river

all the children all the adults gather in this house on the stoep

and my knees are black from a home i can no longer live in because i live

somewhere else now there have been many days

the seven pot bellies around a table the grandfather asking me to choose:

truth or fame

the widow the parliamentarian the poet deceased

in every country on every stage

a collective voice a yearning for something dreamt

something deferred this house is the home that turned my mother’s room

into my brother’s shoulders into a grave into exile

caught my uncles’ hands red between my legs

wields knife against my kin i am a traitor with all my want

singing songs of freedom from my breast

this house spits me out onto the laps of white men

and black men

a mountain is not a hill a river is always a part of the ocean

i did not leave home by choice this poem my father’s home the stage who grew my voice

is a road that leads away from the mountain

the stoep the river the place where others gather

without me

MX: You have published two poetry collections: Undressing in Front of the Window, (self-published in 2015) and red cotton (2018), from impepho press, which you co-founded in 2018. impepho is a ‘Pan-Africanist intersectional-feminist publishing house’, which has produced five titles to date. You obtained a distinction for the MA in Creative Writing that you received from the University Currently Known as Rhodes (UCKAR). You are now a trained and qualified healer. What is your understanding of the relationship between poetry and healing?

vg: Personally, I believe poetry is how my ancestors found me. I have loved poems all my life, nursery rhymes, nonsensical poems, all of it. I remember meeting a young woman who was the daughter of a family friend when I was in primary school. She wrote poetry and was probably in matric or first year varsity. She felt so old to me and took a deep liking to me at the same time. I remember she read me her work, and you know how Gogo Maya (Angelou) says: ‘I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.’ I remember how I felt. I felt like she trusted me with herself. And I felt seen.

I really struggled in my twenties. ‘Mental health’ and multiple diagnoses, dropping out of two major academic institutions and eventually suffering from TB in my lymph nodes. Things began looking up when I accepted poetry as a calling. I knew this is what I wanted to do. So I waitered and took on odd jobs. I snuck into workshops and actively pursued mentorship from some of my favourite poets. I worked on Undressing in Front of the Window and interned for Geko Publishing. I also actively invested in learning about publishing. Then I bought a suitcase, put my printed draft manuscript inside it, and said I wanted these poems to sow me the world. That was 2014. What followed was the opening up of life itself.

Poetry, art, allows for community. To work through, imagine and language life. So there is no separation for me. Poetry is a part of my spiritual practice. How I dreamt of beads but had no way of waking up from my dreams, so I wrote poems in the dark in the middle of the night. And I learned to trance through performance and losing myself to the poem. How I hear poems as codes and messages when people share them with me, and how that informs my editing and healing practice. Poems are portals.

MX: The titular poem ‘Undressing in Front of the Window’ reads like a commitment to start a journey of healing, cleansing and sharing. How would you describe to a high school learner what the speaker is doing in this poem?

vg: So this question is part triggering and part … hmmm … how would I do things differently? Because high school was a terrible poetry experience for me. I really hated the exclusionary nature of the poetry we looked at and how prescriptively we were required to examine it. I also hated how the response to my writing made me feel. Like I wasn’t Stevie Smith or Alfred, Lord Tennyson enough. So I would like to find a way of asking questions rather than prescribing or describing anything, as a way of hopefully bringing the reader into the poem rather than possibly locking them out. So:

How does this poem make you feel?

If we were to consider that this poem replicates the preparation for shedding and release, in that there is an acknowledgement of what the speaker wishes to shed, although we never arrive at it, and it is through the selection of different excerpts as epigraphs that the poem performs the action of undressing, how does this affect your relationship with the meaning you assign to the title as ‘a noun’ or ‘an adjective’?

I would like you to consider how time is used as a literary device in this poem. Consider for yourself whether or not the poet’s choice to tell their life story, as it were, in a non-linear way affects your emotional response to the poem. Does it make you feel hopeful or does it feel like an ending? Does this change when you consider how it introduces the other poems and holds the collection as a whole?

Do the couplets affect the rhythm you assign to the poem and does that in turn affect how the poem moves through your body? Are there musical moments in the poem and do you feel they work?

Does the free-verse lyrical nature of the structure work as an outpouring? Does it help you feel this poem is sincere? Do you believe the speaker?

(In hindsight, I realise the teacher in me came gushing out here, and perhaps your question was for me as the author, but that might require me explaining the poem and I really struggle with explaining my poems because if I have to explain it, I feel like I have to ask myself how successful it is. Lol. Eish … andazi.)

MX: There is such a depth of emotion on the face of the person on the cover of Undressing in Front of the Window! (Undressing.) Please share the process that led to the decision to use this intense-looking cover.

vg: So the cover was originally a photograph by poet and photo-healer (that’s what I call him) Saddi Khali. I loved the photo because it felt like it spoke to the collection and the experience of the photoshoot and what I was moving towards with the book.

To give context, the shoot began with him asking me to stand naked in front of an open window. Without posing. Just stand there, he said. I was deathly awkward. Mortified actually. And though some coaxing and music and conversation, this was me. On a couch, naked, looking out the window, unaware of the camera.

I shared this experience with Tanya and shared the poems with her, and this is what she came up with. And I loved it! It felt like an extension of the collection.

MX: From the poem ‘I will remember this forever’ in Undressing, we read:

later you traded in your locks for an afro

had the most enchanting smile I had ever seen

I imagined touching your cheekbones

letting my hands fall onto your breast

still we never spoke

I dreamt of your voice

imagined you sounded like a spring sunrise

somewhere between a mountain

and a river

I wanted to kiss you

breath you in

taste you

you never even saw me

In this poem the speaker, looking back to their high school days, sounds like they are lamenting unrequited love, maybe reminiscing over a crush? And then comes the line ‘you smell like Sharpeville 2014’ and I got a little lost! Please clarify the reference to Sharpeville in this poem.

vg: Arg! Mam’Khosi! I’m so embarrassed. Why? So, the full image is:

you smell like Sharpville 2014

on a canvas next to a cup of vanilla chai tea

in the mourning

like I have been blind all my life

and you are painted in oil

I was reaching for something ‘poetic’ that broke my heart and was beautiful and devastating and also somewhat removed from me. Something I couldn’t touch but felt deeply. Maybe a scene in a movie. This artist who could touch this thing I longed to access. The ‘black’ experience … being the sheltered girl I felt I was. And maybe, on some level, he couldn’t see me because he was black and I wasn’t black enough.

Of course now I know better, and am less insecure about my blackness. And I cringe because if I have to work so hard to explain it, it couldn’t have been that successful. And it also feels like picking at a scab. It feels like this image tries too hard. I was trying too hard. And it does that thing I now urge young poets not to do: to not insensitively hyperbolise our emotions.

The words that come to mind, from the movie Basquiat:

What is it about art anyway that we give it so much importance? Art is so respected by the poor because what they do is an honest way to get out of the slum. Using one’s sheer self as the medium, the money earned—proof pure and simple of the value of that individual. The artist.

The picture of what the sun does in jail hangs on her wall as proof that beauty is possible even in the most wretched. And this is a much different idea than the fancier notion that art is a scam and a rip off. But you can never explain to someone who uses God’s gift to enslave when you have used God’s gift to be free.

And also:

Because I know nothing of war

I will not use metaphors that do not belong to me.

My parents’ divorce is not a war.

My grief is not shrapnel.

My depression does not flatten an entire village.

My sadness is not a war.

War is war.—Hieu Minh Nguyen

MX: Hmm. Interesting. Thanks for this, I will look up Hieu Minh Nguyen. ‘I will not use metaphors that do not belong to me’ is a great takeaway for everyone.

The late legendary journalist and renowned South African poet Donato (Don) Francisco Mattera wrote the Foreword to Undressing. Why did you choose him for this role? Do you have a favourite poem or two by him? Please share them.

vg: Tamkhulu Don was a mentor and beloved poetry grandfather to me. And I know, because of his immense generosity, he was this to many of us.

For me, to me, he gave me so much affirmation and strength. He taught me that my voice was important and believed in my writing. He took time to know me and with the gentlest, firmest, most loving guidance, constantly reminded me that people are worth fighting for. And poetry is also a way to fight. When he heard about me being kicked off the iShashalazi programme, he called me and told me that if I wanted to stand for the truth, this would only be the beginning. Because not everyone is ready for and embracing of the truth.

So when I told him I was going to publish my book, he asked me how he could help me. I asked what I thought to be the most outrageous request, and he happily obliged. He wrote it by hand so I still have it, and it remains one of the most precious gifts I have ever received.

Ah! Can I also just say, hearing uTamkhulu Don break into a poem mid-sentence is a lost delight. We don’t have a culture of memorising poetry (that isn’t ours) any more. He lived and breathed poetry and spoke it in the way bilingual people move through languages.

I cannot speak enough of Azanian Love Song (first published in 1983 by Skotaville Publishers, then republished in 2007 by African Perspectives), from which I absolutely adore: ‘Remember’, ‘The Poet Must Die’, ‘The Protea’, ‘And Yet’ and ‘Sea and Sand’.

There is a musicality with which uTamkhulu Don writes. He is careful with his words, sharp and not gentle. And he carves his images out of emotion rather than the things themselves. It’s like he speaks human and can pinpoint our attachment, then speaks to that. He is also brave. I come from a political family and uTamkhulu Don calls a spade a spade. With love.

These poems, I have visited often, in my search for hope, in my anger and in my need not to forget. They are beautiful. And they are so telling of him, the man who said his religion is compassion.

MX: Gloria Bosman, the multi award-winning jazz musician, composer and teacher, who passed away in March this year, wrote a cover shout for Undressing. Miranda Strydom also wrote a cover shout. Interesting choices: a journalist–media practitioner and a musician.

vg: Both women influenced me tremendously. As women with their own voices and as women with strong views and their own solid space in the spaces they occupy.

Miranda, I gained deep admiration for when I was studying at the Thabo Mbeki African Leadership Institute. Spending time listening to her convictions and views and how she was willing to stand for them at all costs affirmed me as a politically inclined woman. As an artist. And as a member of the family I come from, with the choices I was making for myself.

And G. Ah man, G is, was and will always be G. We butted heads so much. Had so many differing views and so much love for people. For humanity. As an artist, G helped me learn to articulate how I needed people to show up for me and my craft. She taught me that my method was my own and it was powerful because it was mine. She was always learning and stretching herself as a human who was also an artist. And she was Gloria Bosman! And G. And complicated. And a force.

In essence, I chose women who spoke to the collection, who I was when I wrote it and what I hoped my voice could do. And the fact that they agreed to put their names behind my work, behind me, remains an honour I do not take lightly.

MX: Many of your poems reference women and girls, however, there are two poems that have names of women in the title: ‘A song for Nomzamo Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’ in Undressing and ‘Sis Kookie’ in red cotton. Please write a poem that has ‘Gloria Bosman’ in the title.

vg:

Gloria

where is the wine my friendand who will drink with me when the bottle comes

who will play the chords

and hold me in song

and where is the river that swallowed this country and our hearts what will happen to the room we built

where nothing was erased

where love was an explosion behind a door

and tears and jazz

and i was maybe a little off tune

what will happen to the chicken left unplucked in the village

where we were both with our loves then

you are gone now you have left

and mine is gone now left

but you will not return

my friend this wine will make a drinkard of me

if i am to drink it alone

MX: The poem ‘I want to speak to my children’ in Undressing is so rich with the history of Africa, I imagine history teachers are using it in their classes. There is something evocative about the references to ‘the youth of 1976’; ‘the children of Sierra Leone; ‘the lost boys of Sudan’; ‘the Cradle of Humankind’; ‘Nubian truth’; ‘Kush’; ‘Isandlwana’; ‘El Obeid and Sheikhan’; ‘land of Adwa’; ‘Menelik and Taitu’, to mention just the list from the first three stanzas. Please share your experiences of learning about any three historical narratives you reference that you were not taught in school.

vg: Sadly, I didn’t do history in high school and only encountered some of these in varsity history, which was also dubious—limited to Hector Pieterson and Soweto, byproducts of corrupt African leaders and myths or archaeological speculations.

I wrote this poem for the Thabo Mbeki Foundation, fully aware that at least four former heads of states would be in attendance. I worked very hard on the research to ensure I would have the language for the poem that wanted to be written.

On the Kush: This was a reminder for me that it is by design that we forget ourselves. That we fight for the memory and prestige of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire and the theft of Plato but make no mention of the Kush. Because Arabic colonisation is something we choose not to dig into. As if it was a glitch and precolonial refers only to Western and Christian colonisation. So it felt important for me to stretch back before Arabic colonisation too.

And the complication is that colonial history is also black history. Our stories are intertwined and the lessons (and/or victories) are not always clear-cut or where we expect them to lie. Black or Nubian people resisted colonisation and continue to do so. The war in Sudan is nothing new. It has been ongoing for centuries, and is a colonial struggle. And we are not from a people who gave up or never fought or gave up our land for our reflections in the mirror. And our history is also architectural and mathematical and astrological and scientific and Pythagoras stole from thieves who also stole from Nubians. Abantu. The Kush.

But there are very few places I find to have as contentious and complicated a colonial story as the horn of Africa. Mostly because my ideas around who is historically black within the Arabic–African conversation comes into question. And is opened up, which then opens up a conversation around humanity, and Africa is the heart of humanity and never monolithic. Because the Battle of Adwa was monumental and important when we speak of European colonialism, and preceded by the wiping out of the Dʿmt people by the Aksum who proceeded to help spread Christianity, and that is a form of colonialism as well.

For me, it is important for me to acknowledge that I have a white grandmother in my bloodline, that the victories and the losses are a part of our history, and ultimately, I need to not be written out of my own history.

I am still learning and tracing back and remembering. And I think this poem opened me up to the vastness of blood and the importance of knowing who you are so as to know what not to answer to.

MX: What led to the decision to start impepho press? And how did you choose the name?

vg: I will answer for me, because I cannot speak for Sarah and Tanya (though I know that for all three of us, the answer to every question was and is books and archiving). During my MA year, I spent a lot of time searching for women writers and characters who lived on the outskirts. I remember reading Bessie Head’s Life and thinking to myself, how fantastic is this woman? Women who chose for themselves who they were, outside children and family and morality. Sometimes because of these things and sometimes in spite of them. Women who were complicated and chose themselves fiercely. And made brave, sometimes contradictory choices and were from this continent. I loved reading Calixthe Beyala for the same reason. How she put the grotesque and the beautiful in the same sentence as if they were the same thing.

I guess I came into the MA wanting to be thrilled by complex black women characters in South Africa who were neither villain or saintly, and I found myself looking abroad for them. And I admit, maybe I needed to look further, but I felt like I could not find myself. But I knew I existed. And we existed. And by the time I completed the MA, my obsession with immortality and fear of dying as if I never existed had become insurmountable.

And this was all happening during a spiritual awakening and against the backdrop of me having self-published and interned in publishing as a way of understanding how it worked. Archiving felt like a natural progression.

When I shared this obsession with Sarah Godsell (who I had worked with on a number of projects and who had become one of my dearest friends and confidants) and Tanya (who I had already worked with on Undressing in Front of the Window and Umnikelo ka Mthunzikazi Mbungwana) it felt right. True. Honest. Like we all met at the same intersection and were dreaming in the same direction.

The name came. It came from our collective commitment to being a part of something healing. Something that builds and is pro-something. Impepho is an indigenous species of wild chamomile found in Southern Africa and usually burned to communicate with ancestors or clear spiritual pathways, and it can also be used as a calmative—one of its many healing properties. It is also what I consider to be the base plant for spiritual cleansing or work.

Tanya, Sarah and I want to create books that create pathways. That are haunting and tell human (women’s) stories, pretty and ugly, with sincerity and skill. So we decided that even if we could not write them ourselves, we would find them, and we would publish them. As an offering. And as a pathway.

MX: The five titles from impepho: your second collection red cotton, Busisiwe Mahlangu’s Surviving Loss; Danai Mupotsa’s feeling and ugly; Sarah Godsell’s Liquid Bones; and Yesterdays and Imagining Realities: An Anthology of South African Poetry. They are truly impressive titles that I have enjoyed reading over the years. Congratulations! I cannot imagine how labour-intensive publishing must be. How do you balance the intellectual and creative labour that writing your own poems requires with the manual, intellectual and creative work that running and managing the publishing house demands?

vg: Thank you. I am very proud of the work we have done. Both in the books that have been published and the work that we have done that has not made it to the printing room or been published with our logo on it.

I don’t find the balance. I wish I did, but I really have not been able to. My own writing has suffered tremendously, and I have only recently begun coming back to it. I have also suffered a lot from imposter syndrome because I think I fell into the trap of editing myself as I was writing. And feeling like everyone was writing something more worthwhile than me. Motherhood, freelancing in a pandemic and a collapsed gig economy, falling in love with other aspects of arts administration and ukuthwasa have also split my focus into more pieces.

But I don’t feel as guilty about it as I did before. It’s how life is sometimes. I embrace Shonda Rhimes’s words: ‘Whenever you see me somewhere succeeding in one area of my life, that almost certainly means I am failing in another area of my life … That is the trade-off.’

MX: A partnership between the French Institute of South Africa and impepho press, with the support of Total SA, resulted in the publication of Yesterdays and Imagining Realities. What inspired this collaboration, which shows ‘support to plurilingualism’? How has this anthology been received?

vg: The anthology has been fairly well received. Sales-wise, it has fared better internationally than in South Africa, and the feedback we received was encouraging. There were some who felt it could have been a bigger anthology. Many people enjoy that they are able to read different languages in one book. People have really loved the interaction with the artwork. Overall, I think those who have come across the book have enjoyed it.

MX: In the anthology you wrote about your reflections as a judge that you ‘know the weight of rejection.’ Please write a poem that captures the weight of your knowledge of this kind of rejection.

vg: I’ve written so many drafts of nothing I wish to share with anyone. Everything feels pretentious. Like those four-line ‘deep’ statements that might be shared on Instagram. I just can’t.

I just want to say, I know the weight because I get rejected all the time. And every time it hurts. And every time it surprises me just as much as an acceptance letter. And every time it takes me a while before I can trust myself enough to try for something else. I don’t know how to write a poem that says that.

MX: Each time I revisit red cotton I am reminded that minimalism lives happily on a book cover. You did the same with the cover of Mupotsa’s debut collection, feeling and ugly. How did you arrive at the choice?

vg: Tanya is the beautiful heart behind most of our covers. We call her the poem whisperer. She reads through collections and collaborates with the writing. She also created our corporate image.

For red cotton, I learned (through Tanya) that men are more prone to colour blindness, and there is a specific type of colour blindness that makes people (and more likely men) unable to see this combination or red and blue as their true colours. And with feeling and ugly, Tanya wanted to create something that felt like a leather journal. I am oversimplifying it, no doubt, but when we saw the covers, we loved them. And believed in them.

MX: When I interviewed you on poetry and indigenous languages for the anthology Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000—2018 (2019), you said, among other things, ‘Most of the South African population speaks isiZulu. Surely this should count for something!’ What has impepho press done since its inception—over and above the anthology mentioned above—to make this count for something?

vg: I wish I could tell you we have published a Zulu collection but we have not. In fact, though we have traces of bilingualism in our collections, we have not published a full length collection in any South African indigenous language. There is a Xhosa collection I wish we had published, but I guess it wasn’t meant to be. And there are no doubt collections in our future, but as yet, the Yesterdays and Imagining Realities is it.

MX: What titles are forthcoming from impepho?

vg: I honestly cannot name the titles because I don’t believe in naming chickens before they’ve hatched. But I can tell you we are excited about two brilliant collections, a delightful trilogy of children’s stories and a speculative fiction novel written in verse.

MX: I hear you. You refer to red cotton as a poetry novella. Imagine you are talking to a class of Grade 6 learners; how would you describe this genre?

vg: Ordinarily, a novella would be a story that is longer than a short story but not as long as a novel. A baby novel. The only difference is that this one is written using different kinds of poems. Long, short, free verse, in form, a collection of poems that if read from front to back, reads like one story, and if enjoyed haphazardly, reads like connected poems in a collection.

The story itself has characters and a thread but is most likely to use some minimalistic tools. So maybe the language will be cut down so there isn’t as much detail as there would be in a novel. Or maybe some themes will be introduced and left to simmer instead of being carried through. It might only choose to tell the story from one perspective.

The most important thing though, is (unlike this answer) novellas are not usually as wordy as novels and have a story arc. And poetry uses rhythm and imagery to create an emotional throughline, so it should make you feel something, as if you were reading one long poem.

MX: Reading red cotton for this interview reminded me of just how much pain pulsates throughout the collection. The collection is a product of your MA thesis. You mention:

‘My collection of poetry is a deeply personal exploration of what it means to be black, queer and woman in modern-day South Africa. The collection moves fluidly between the erotic, the uncomfortable and grotesque, what is painful, and what is beautiful and longed-for.’

Readers encounter rape in real life and in dreams; fires and allusion to fires via embers and flames; brewing storms; violence; blood and death here, there and everywhere; animals, reptiles and insects; and many more scary characters and events. The ubiquity of pain abounds. But it is also inviting because most of the poems are founded on the ordinariness of home life, domesticity and family; there is uTata, uMama, uMakhulu, an aunt, uMakazi, a ‘smallgirl’ and more. This is powerful writing. Would you call this baroque poetry? I am running out of ideas. I have the need to name it.

vg: Honestly, mam’Khosi, I would not name it. And if I did, I’m not sure that would be the first name to come to mind. (Probably because I wasn’t actively seeking it out and have to fight a natural gag reflex when put into a bucket with dead white men, though in spite of ourselves sometimes, we become what we become.) I understand why you would go there, because of the fluidity of everything, and life inside water is difficult to comprehend if all you’ve known is land.

I don’t think this was a deliberate attempt at creating a distorted world. I don’t believe I extend metaphor and deliberately shy away from flowery writing to be anti-anything. I think, in this book, I was beginning to remember, and in order to not drown in it all, I had to take small bites and spit them out as they were. The half-rat woman is real. If I dream a cockroach is coming out of my vagina, it is. I experience it. And then I have to find out why. My idea of metaphor is using images to describe things for the sake of poetics. I am saying I saw them. As they are written. I am saying that time is not linear. And this body carries more than one spirit and not all of them are human. And this is clearer now, but when I wrote red cotton, it was all flashbacks and sleepless nights and as violent as it was—is. Not the hyperbole of the Sharpeville massacre in Undressing.

But let us try name something … a few years after releasing red cotton, I met Kathy Engel, who introduced me to zuihitsu, a Japanese creative essay style or artform that is non-genre and ‘follows the brush stroke’. A collection of fragments that do not always fit, but fit. Create something. I feel like without knowing it, this is what I was attempting. And maybe if I had read Lily Hoang and Kimiko Hahn in 2016, I would have been more intentional about it.

MX: I enjoyed the surprising and discomforting images sprinkled all over red cotton. In ‘taxi ride’, for instance:

the sandpaper reaches for the ashtray in between my legs

…

the grey head man is ogling my chest

the gear stick makes one last attempt on my thighs

Most women are familiar with this context, the violence of men in public transport spaces. Poems like this one speak for most of us. It seems to me that your professional healer role embraces poetry as one of the methods. Would you agree?

vg: I may have said this before but I actually feel like poetry led me to understanding myself as a healer. Opened me up to the many cuts and balms of healing. And yes, too many women are familiar with this context.

MX: Poems like ‘sleeping next to you’ that suggest some eroticism also deliver discomfort and far-from-erotic surprises, yet the intimacy lives on.

I searched for you frantically.

Found you in a torn latex wrapper in the dustbin.

Found you in a bite mark on your arm.

A stray scent.

A spiteful strand of hair.

Please share the writing process that led to this poem.

vg: I can’t remember what the prompt was, but I do know it was a memory of an ex that got me thinking about signs, namadoda angamaxelegu and how perceptive women are. It might have been the product of a free-write though.

MX: The commonplace sounding title ‘the corner of our ceiling’ delivers a haunting poem. The first and the last stanzas:

There is a room in the house we share

That neither of us may enter

We had not noticed it before, when we used to talk

Now the silence rattles the door

A gentle back and forth against the frame while we sleep

We blame the silence in the room

The door we cannot open

We share a bed on which we never touch

Our roof leaks. We do not fix it

The mould on the corner of our ceiling

Is the only conversation this house knows

I had hoped that the ‘our’ in the title will deliver some love, connection, eroticism, maybe? Again, I am curious about the process behind this.

vg: In this poem I was exploring separation. Living with someone and being alone. Feeling like all that holds you together is that you live under the same roof, but it feels like living in a haunted house. Or the home of a couple who have lost a child.

As with many of these poems, it sat heavy in my chest. The feeling. And then I saw the room, and the house and the image. And then it poured itself out.

MX: Phillippa Yaa de Villiers is a prolific poet of three collections: Taller than Buildings (2006), The Everyday Wife (2010) and ice cream headache in my bone (2017). She is a trained theatre practitioner with many years of experience in South Africa and internationally. She currently teaches creative writing at Wits University. You chose her to edit Undressing in Front of the Window. What were your take-aways from this experience that you have continued to use in your role as a publisher?

vg: From Phillippa I learned to listen with my heart. She feels the poetry, like she’s watching a butterfly move on her skin and breathing in what that does to the rest of her body. I remember I had asked two other, really lovely people, to look at my manuscript before. Dr Pumla Gqola, who ripped its original version to shreds and really helped me take a collection of things I had written and turn them into a collection, and Dr Raphael d’Abdon, who really helped me trim a lot of the fat. But Phillippa reached into the work and listened in the same language as me. And I have valued that since.

I don’t have an intellectual response to poetry. I guess I can reach for one if asked to, but it doesn’t come naturally for me. I feel it. Hear it. And having an editor who works in the way Phillippa does helped me to trust that.

She’s also incredibly generous with those emotions. So she extends the ‘when you do this, it feels like’ to other poems, in ways that teach. That helps you as a poet learn to listen to your work. Phillippa left me feeling like I had a sense of what I wanted my voice to sound like and that gave me confidence. I hope I leave the poets I work with feeling the same way.

MX: Why was it important to you to study creative writing at a university?

vg: I think it is important to study—by way of intensively and deliberately dedicating yourself to learning—anything you love and want to be good at. No one exists in a vacuum, and for everything you are attempting, there is someone who has also attempted some variation of the same thing. So I think of it as an ecosystem. Where we are fed and where we water to replenish. When it works. When it does not break you or kill you.

I also think the beauty of postgraduate study versus undergraduate is that in the former you are encouraged to bring your own thinking and voice into the work. If you have the right supervisor, you are able to grow your thinking and stretch yourself into something beyond anything you might have previously imagined before. I struggled with how undergrad wanted me to mimic and become a parrot, but I love critical thinking and being required to think for myself.

I love that actively interacting with the writing community in a critical, deliberate and intensive manner helped me to grow into my own voice and find my artistic obsession. (Because I believe every artist has at least one obsession; that thing they cannot let go of that shows up in all of their work.)

MX: Hidden behind a paywall online is an interview that Maneo Mohale, author of Everything is a Deathly Flower (2019), conducted with you, which I couldn’t access. ‘Everything is red cotton’ is the first part of the delicious title of this interview. What do you consider to be key ‘points of convergence and divergence’ between your poetry collections?

vg: Everything is a Deathly Flower is such a delicately and deliberately painted collection. Stunning! So I feel deeply warm inside to have our books sit side by side in any way.

Maneo creates, finds, moves through a garden and I think I am in search of water, but we both begin with our mothers and the bible. Literally. Though I think in ‘Letsatsi’ Maneo is trying to locate themselves and in ‘I’m standing in the middle of the road’ I am trying to tear myself away … or we both know that something about us being queer is the knife that cuts us from our mothers. I think we both move through this black female-assigned body within the context of this place and its multiple violences, but Maneo explores being queer as more of a fore-identity. In red cotton queerness is there as a matter of green and today the sun came up, whereas for Maneo it is skin and breath. Both collections are deeply revealing of the personal and place a lot of trust in their readers.

I think one of the main points of divergence is that Maneo is in conversation with their reader whereas I am not even sure if the words are coming out of my mouth or if I am even awake. And there is a romantic air about Maneo’s work. The language, the flowers, the colours, the eros, even the shadows. The moments are romantic. So we differ quite drastically in style.

MX: In ‘Sitting Beyond the Fire: A Reflective Essay’, a section of her MA thesis, Nondwe Mpuma, author of Peach Country (2022), mentions your poem ‘breathing under water’ in her discussion of poetry that focuses on memory and rituals. What is your take on her reading of this poem?

vg: I think she’s quite right in noting that the mother and daughter differ in beliefs. I worry about (though understand) the connection she draws to the madness in Lidudumalingani’s ‘Memories We Lost’. I think in this poem, beliefs and memory present the possibility of freedom rather than madness.

MX: How have literary scholars in South Africa and abroad responded to and engaged with Undressing and red cotton?

vg: Very well actually. Better than I could have dreamed. ‘I expect more from you’ has been the winning poem for Poetry for Life for at least two consecutive years and continues to be a poem of choice for the participants. The poem has also gained a notorious underground following of people sharing, tagging and encouraging others to vote. A social campaign of sorts. And ‘I want to speak to my children’ has been used by the Thabo Mbeki African Leadership Institute as the theme poem for years. It continues to be a favourite when I perform internationally. It really takes life in musical collaboration.

I’m constantly surprised by people who identify with red cotton because it’s taken me some time to come back to loving it. The MA was brutal, with many of the male teachers and fellow students making me feel quite ashamed of it. As though it were basic and not of any real value. Yet at least once a month, I get a message from or an interaction with someone wanting to purchase it, quoting it or affirming its importance to them.

red cotton has recently been added as prescribed reading at State College in Pennsylvania. And during a reading with Nikky Finney, she stopped and asked everyone to acknowledge that something special had happened. Her words: ‘I want to stand on the corner of the road and gift every black woman I see this book. Here sis. You’re alive. You live. You deserve this.’ I will never forget that moment.

smallgirl has also become a movement. I tour smallgirl rising (we’ve done four states in the USA and are beginning our African tour in October). I am always moved by the number of women, and queer people, who identify as smallgirls. Who get it. And are empowered by it rather than demoralised.

MX: What? OMG! You read poetry with Nikky Finney? In 2019 a friend, Stéphane Robolin, introduced me to Nikky Finney’s poetry via her National Book Award acceptance speech. We sat in my office at WiSER, watched and listened to her. And then two years later he gifted me Head Off & Split. We need to talk more about this later …

Your poetry has opened the world for you in interesting ways. Please talk about the places you have travelled to because of poetry and share your top three positive experiences.

vg [smiles]: The USA (here I’ll list the states because the country itself is about three-quarters of a continent: Washington, D.C., New York, Pennsylvania, Atlanta), Gabon, Mozambique, Algeria, Morocco, Côte d’Ivoire, Malawi, Sweden and Ghana (by the time this interview goes live).

At the top of the list are Malawi and Côte d’Ivoire. Malawi, because Q (Malewezi) was a brilliant host. I was invited for the launch of his first audio offering, People, and we were able to tour different parts of the country leading up to the event. I was able to work as both a performer and a facilitator in ways that opened me up and taught me about what I was claiming to do. I learned about guiding and holding space for people to go inside their poems, in Malawi. I learned about making sure they come back. And I learned about the kind of community that demands you show up in your biggest, most talented, most alive state. (More often people want you big here and smaller there. Q said: bring everything or stay at home.)

Côte d’Ivoire: Abidjan, Babi Slam. The people. The warmth of the people. And the authenticity of the experience. I loved that Bee Joe (Baffrou Joseph) did not try to take us to the fancy parts of the city. He was intentional about curating an experience wherein we, the participants, could fall in love with the soul of Abidjan. Eat at the night market, catch public transport and interact with the people we were making these poetic offerings to. I remember us being on a boat taxi and spontaneously bursting into poems. And what a fantastic group of poets to have shared that experience with.

New York 2023, smallgirl rising. Because we were able to dream a tour into life and execute it. We visited four cities: State College, Philadelphia, DC and New York, and each city gave us something special, but in New York, the four women behind the vision (myself, Dr Mandisa Haarhoff, MoAfrika wa Mokgathi and Wéma Ragophala) were able to be in the same place and enjoy the splendour of what we had created. Mo and I performed at the historic Billie Holiday Theatre and at the twelve-year anniversary of Women Writers in Bloom. We were able to teach at NYU Tisch, and CUNY LaGuardia and I was invited for an unscheduled and paying gig at Open Street in Queens (an affirming answering of my prayer: may the work we do open up to more work). And personally, I was able to meet a friend I had worked with and known for years without having met in person, spend time with friends and chosen family, listen to Claudia Rankine live, drink wine, be spoiled rotten and remember that the world is indeed the playground my father promised me it was.

MX: Oh wow! You were a writer in residence in Gothenburg, Sweden in November of 2021. First, how would you summarise this two-week experience? Second, what was your take-home lesson?

vg: In my application, I was very clear that I wanted to commune with black people. Women, predominantly, but I wanted to draw on the lessons and parallels between being black in (South) Africa and being black in the diaspora. I also wanted to get away from home. From full-time mothering and being everything but a poet. I wanted to remember that I am also a poet. And a part of the story (and its telling).

The residency allowed me to do exactly that. I met with a number of black creatives and activists, including members of Afro Institution. I was able to have conversations and build community in a way that strengthened some of what I know in my spirit and energised the urgency of the healing and archiving work I need to do. I knew almost nothing about the Afro-Swedish community before going to Gothenburg. And having an entire front row of black creatives and voices at my final reading was humbling and invigorating. The South Africans and local Afro community understood what I meant when I spoke of the Divine Black Feminine and the need for healing. They saw the value of archiving and taught me the ways they are already involved in programmes of re-coding as a way of redressing intergenerational trauma. In a way that was not exotic. In a way that was human and home.

I think the take-away was that there is more that connects us than sets us apart. There is a lot of hurt in this world. And there is also a lot of light. A lot of hope. People are kind and generous. Our stories are vast, our memory is deep and untapped. I am delighted to be a part of the archive, as breath, as writer, as mother and as publisher.

MX: You have also been a producer (or is it director?) for poetry productions, namely Katz Cum out to Play, the State Theatre’s Night of the Poets and Human4Human. What were the most valuable lessons from doing this kind of work?

vg: Producer. Yes. I organised these productions from scratch, Katz in collaboration with Zoya (then Mabuto), Night of the Poets under Black Eagle Media Group and Human4Human with Sarah Godsell. We dreamt them, fundraised or hustled or conned people into believing we could pull them off.

Human4Human was the most humbling. We worked with Monageng ‘Vice’ Motshabi, who let us know that we had no idea what we were doing. He came on board as a dramaturg and really brought the production to life. Pamela Nomvete grew it, Jefferson Tshabalala also added to it. I had no idea how little I knew about the difference between performative poetry and theatre. And I learned to respect craft. All craft. Always. It was expensive and expansive and in hindsight, I learned that we are not all always ready to have the conversation. Even if we vibe really well as artists. We may not all be at the same place. And that’s okay.

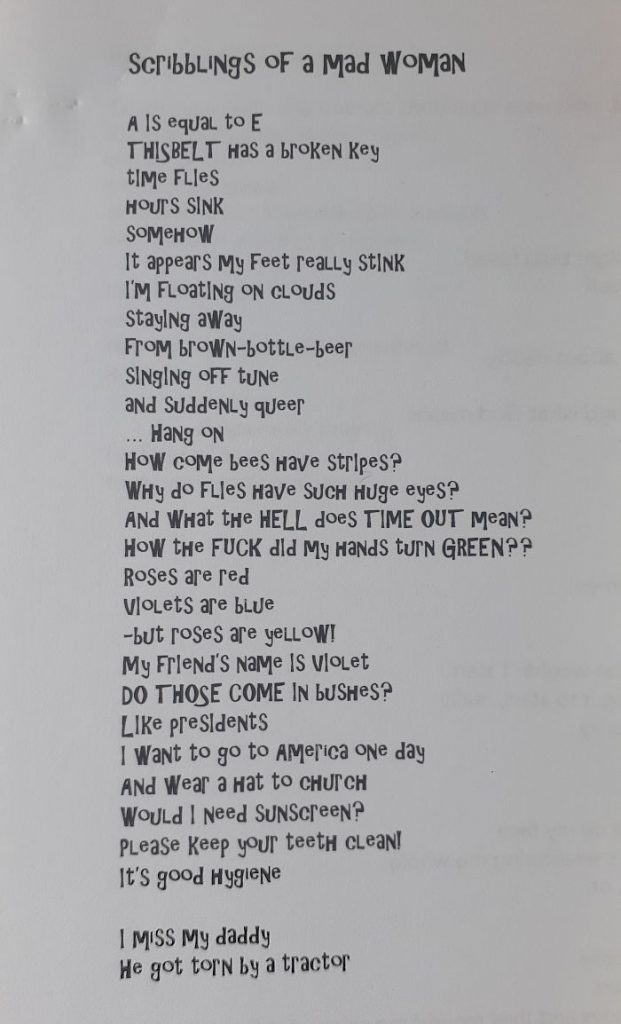

MX: Let us end this interview with you sharing ‘the scribbling of a mad woman’, a poem in Undressing. I enjoyed how the font you chose for this poem speaks louder than words.

vg:

MX: Thank you for availing yourself for this interview.

- Makhosazana Xaba is a Patron. She is the author, most recently, of Noni Jabavu: A Stranger at Home, co-edited with Athambile Masola; the collections of poems The Art of Waiting for Tales (Lukhanyo Publishers, 2022) and The Alkalinity of Bottled Water (Botsotso, 2019); and the editor of Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000–2018 (UKZN Press, 2019). She is Associate Professor of Practise in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Johannesburg.

One thought on “‘I believe poetry is how my ancestors found me’—vangile gantsho in conversation with Makhosazana Xaba”