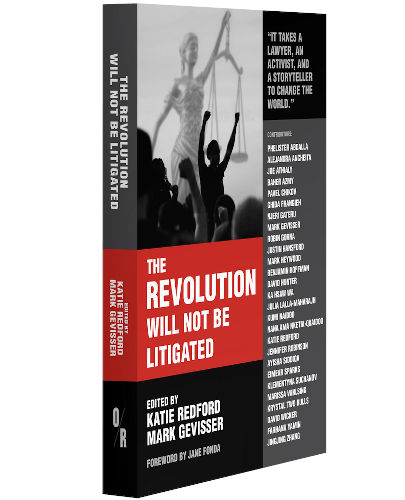

The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated: People Power and Legal Power in the 21st Century, edited by Katie Redford and Mark Gevisser, is out now from Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Written from the maxim ‘it takes a lawyer, an activist, and a storyteller to change the world’, The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated shows how the law and social movements can reinforce each other in the struggle for justice and freedom.

In these vibrant narratives, twenty-five of the world’s most accomplished movement lawyers and activists become storytellers, reflecting on their experiences at the frontlines of some of the most significant struggles of our time. In an era where human rights are under threat, their words offer both an inspiration and a compass for the way movements can use the law—and must sometimes break it—to bring about social justice.

‘Every person in this book has spent their lives acting like the house is on fire and responding to the world’s most pressing problems with the urgency they deserve. But more than that, they are offering a roadmap for doing what is often considered to be impossible, but necessary. They are the true leaders that the world needs to listen to and follow.’—Greta Thunberg

The contributors here take you into their worlds: Jennifer Robinson frantically orchestrating a protest outside London’s Ecuadorean embassy to prevent the authorities from arresting her client Julian Assange; Justin Hansford at the barricades during the protests over the murder of Black teenager Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; Ghida Frangieh in Lebanon’s detention centres trying to access arrested protestors during the 2019 revolution; Pavel Chikov defending Pussy Riot and other abused prisoners in Russia; Ayisha Siddiqa, a shy Pakistani immigrant, discovering community in her new home while leading the 2019 youth climate strike in Manhattan; Greenpeace activist Kumi Naidoo on a rubber dinghy in stormy Arctic seas contemplating his mortality as he races to occupy an oil rig.

The stories in The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated capture the complex, and often-awkward dance between legal reform and social change. They are more than compelling portraits of fascinating lives and work, they are revelatory: of generational transitions; of epochal change and apocalyptic anxiety; of the ethical dilemmas that define our age; and of how one can make a positive impact when the odds are stacked against you in a harsh world of climate crisis and ruthless globalisation.

The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated has a foreword by Jane Fonda, and the contributors are: Phelister Abdalla, Alejandra Ancheita, Joe Athialy, Baher Azmy, Pavel Chikov, Ghida Frangieh, Njeri Gateru, Mark Gevisser, Robin Gorna, Justin Hansford, Mark Heywood, Benjamin Hoffman, David Hunter, Ka Hsaw Wa, Julia Lalla-Maharajh, Kumi Naidoo, Nana Ama Nketia-Quaidoo, Katie Redford, Jennifer Robinson, Ayisha Siddiqa, Eimear Sparks, Klementyna Suchanov, Marissa Vahlsing, Krystal Two Bulls, David Wicker, Farhana Yamin and JingJing Zhang.

Watch an introductory video:

Read an excerpt from Katie Redford’s essay, ‘The Lawyer’s Perspective on Doe v. Unocal’:

JANE DOE 1 VERSUS UNOCAL

Katie Redford

Here’s how I remember my first deposition. It’s also my first memory of what it really means to be a radical lawyer.

It was the rainy season of 1997. I sat in the unnaturally cold, sterile hotel room in Bangkok.

We were suing the American energy company Unocal, which had built a pipeline through Burma with the brutal aid of the Burmese military government, and our first plaintiff was up. Jane Doe 1 walked in, wearing flip-flops and her sarong, and sat down at the long conference table with me, her other two lawyers, and Ka Hsaw Wa, the activist from Burma who had led the clandestine efforts to gather evidence and witnesses for our case. Directly across from us were the lawyers from Unocal, the multinational oil company. All of them were stern Americans in dark suits. Jane Doe 1 was 4’10” and one hundred pounds at most, and they towered over her. They were the big guys in the room (literally) and they knew it.

At the head of the table sat the court reporter, flown to Bangkok from Los Angeles to transcribe the sworn testimony of all of our clients. The deposition began. After the initial formalities—name, age, Where do you come from?—a Unocal lawyer asked her a series of questions, including whether she knew why she was there that day.

Seems like a straightforward question, but at that early stage in our litigation, it confirmed what we already suspected about Unocal’s theory of the case, and how they planned to defeat us. In Doe v. Unocal, the corporation talked about the case in ways that dismissed our clients and their lived experience—arguing that activists and political dissidents, like Ka Hsaw Wa, were using people like Jane Doe in a growing global movement that aimed to isolate and then overthrow the Burmese regime. They similarly suggested that anti-globalisation and anti-capitalist activists were using our clients to paint negative pictures of corporations and what they did overseas. Or that our clients were pawns of environmentalists, who hated the pipeline because of its path through rain forests. They described our clients as victims of activists and movements who sought to use them in their own political battles. And they portrayed us, their lawyers, as militants using the legal system inappropriately for political and advocacy gains.

So when Unocal’s lawyers asked Jane Doe 1 if she knew why she was there, they were probably hoping and expecting that she would say something to validate such claims. Something like: ‘I’m here because EarthRights told me to be part of this lawsuit.’ Or: ‘I’m here because Ka Hsaw Wa asked me to come.’ Instead, what they got were words to this effect: ‘I’m here because your company and the soldiers killed my baby and I want justice.’

Silence.

After what seemed like a long moment, one of the lawyers blustered, ‘Move to strike, unresponsive’—an attempt to get the answer removed from the record. Judith Chomsky, one of our cocounsel, leaned over toward me and chuckled under her breath: ‘It was responsive, it just wasn’t the response you were expecting.’

In that moment, an early moment in a case that would take ten years, I felt like we had already won. In that moment, Jane Doe 1 was the most powerful person in the room, and everyone knew it. Most importantly, she knew it. It was at that point that I realised that one of my most critical roles, as her lawyer, was to open the door for her; to provide a forum for her to tell her story, to face those responsible, and to demand justice.

In the end, although we never went to trial, we ‘won’ a successful settlement. Unocal paid a whole lot of money to our clients and the communities it had harmed. Jane Doe 1 was delighted to get the payout, but she told me that, for her, the money was not the win. The remedy for which our justice system allows—money—could not give her back her dead baby. It could not buy back the freedom and dignity lost by our clients forced to work as slaves on Unocal’s pipeline project. The win was the process itself: the agency that Jane Doe 1 and her fellow litigants exercised in seeking justice for themselves, and then being part of a precedent-setting case that would open similar doors for others from around the world. That’s what gave them power—and that power was there whether we won or lost the case.