The JRB presents an excerpt from Freedom Writer: My Life and Times by the late Juby Mayet.

Freedom Writer: My Life and Times

Juby Mayet

Jacana Media, 2022

Read the excerpt

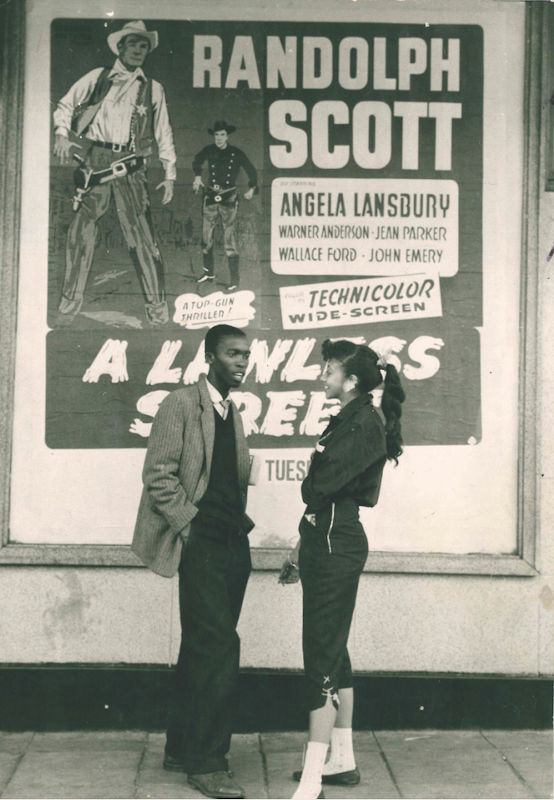

After we had finished the mid-year exams and were just messing around, waiting for college to close for the July holidays, Spooky one day said to me, ‘Come—you and I are going for a walk …’ He wouldn’t tell me where we were going, but it was one helluva long walk. From the college in Fordsburg, through the centre of Jozi, down Main Street—and I suddenly knew where we were headed. When we stopped at the corner of Main and I think Polly Street (right opposite 174 Main Street, home of the then mighty South African Associated Newspapers), Spooky said to me, ‘Okay, in you go—you want to be a writer, so take your first step now!’ (I had in fact already taken my first step, but more of that later.)

Spooky pushed open the door, with me trying with all my strength to pull away, and got me inside. Terrified, I stood there as he stepped back outside and shut the door on me and a somewhat puzzled David Sibeko (now long deceased) enquired if he could help. Switchboard operator/receptionist (of course, I only learnt who and what he was later), Sibeko was the first person I met at the offices of Golden City Post newspaper and Drum magazine. I blushed a fiery red and was unable to get a single word out until Spooky came back inside to rescue me.

Spooky politely greeted Sibeko and announced, as if it were the most normal thing in the world, ‘She’s my girlfriend. She wants to write, so I brought her here to meet some of the reporters she’s always talking about. Would you be so kind as to help her? I have to go somewhere, but I’ll be back to fetch her in a couple of hours or so …’

Before I continue, I need to talk about Sibeko, who was born in Johannesburg in August 1938. He was educated in Sophiatown and later at Madibane High School. After completing schooling, he joined Drum as a switchboard operator. In 1963, after he had spent seven months in jail on charges under the Sabotage Act, Sibeko skipped the country and joined the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) in Tanzania. He was put in charge of the organisation’s missions in Europe and America and later became a permanent observer of the PAC at the United Nations. He was appointed director of foreign affairs when he became a member of the PAC’s central committee in 1975. But Sibeko became a victim of the internecine strife and distrust within the organisation’s leadership and was shot and killed by PAC members in 1979.

I didn’t get to know Sibeko as well as I did most of the other guys at Drum and Golden City Post, I think, mainly because he was not full-time in the newsroom during my early days there, but I remember him as a jovial person who bristled with passion for the PAC.

To get back to my story … I nearly died of embarrassment in the lobby with Sibeko because, despite my extrovert air, braggadocio and mischievous exploits in high school and college, I was an extremely shy person who would rather bury her nose in a book than be out socialising. I was terrified of strangers and meeting new people.

However, there I was in the offices of Drum and Golden City Post, thrown in at the deep end and left to my own devices. Sibeko spoke on the phone to someone upstairs, explaining that a teenaged female wanted to meet reporters. I cannot recall (forgivably, in the circumstances) who came down the circular staircase to fetch me.

I was taken upstairs and found myself face to face with the likes of Todd Matshikiza, Bloke Modisane, Arthur Maimane and Gwigwi Mrwebi, among others. I told them my name was Sharon Davis (I’ll explain this shortly), that I was still attending college but was very keen on writing. I think they were as taken with me as I was with them and much to my amazement, I soon forgot where I was as I was shown around the offices, the photography department and so on. I’m not sure, but I think it was Modisane, the social pages editor, who suggested I freelance for the paper while I was on holiday.

For those who may not remember or do not know who William Bloke Modisane was, he grew up in Kofifi and started working for Drum in the early nineteen-fifties. He wrote several short stories that were published in the magazine. He left for England in 1959 and a few years later his book, Blame Me on History, was published. He worked variously as a writer, actor and broadcaster in exile, dying in West Germany in 1986.

Thanks to Modisane, it came to pass that I found myself covering the social scene, doing little write-ups on twenty-first birthdays, dance evenings, weddings and suchlike. During this period I wrote my first front-page story for Golden City Post, under the wing of Lewis Nkosi. Born in Durban in December 1936, Nkosi worked for the Zulu/English newspaper Ilanga-lase Natal before he joined Drum and later Golden City Post where he was chief reporter in the late 1950s. Journalist, author, critic and later broadcaster, he accepted a fellowship to study journalism at Harvard University in the United States in 1961 and became an exile. Nkosi wrote several books, his first novel being Mating Birds while his last, Mandela’s Ego, was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Literary Awards in 2007.

Anyway, back to my front-page story. It was about a missing child who, incredibly, was found two streets away from my home in Ophirton—after Nkosi and I did the necessary investigations to solve the mystery.

It was on the strength of this story that Golden City Post editor Cecil Eprile offered me a job as a cub reporter, starting immediately. Unfortunately, Mummy and Daddy would have none of this—I had to finish my teachers training course. I had less than six months of college to complete and after I explained my predicament to dear old Cecil, he said he would keep the job open, but I was to report to him the minute I wrote my last exam.

As fate would have it the last few months of that year were somewhat stressful for my family. My mother was rather badly injured in a car accident during a violent highveld storm. The car had been driven by the son of one of my Daddy’s friends. He hit the brakes and we skidded on the tramlines in Bree Street near where the Market Theatre precinct now stands. I don’t remember the full details of the accident, but my mother suffered a broken leg and arm and badly cut upper lip, which required several stitches. Some of my siblings were also in the car but fortunately we were all okay apart from assorted bumps and bruises, and one of them (Julie again, I think) sported a magnificent shiner for quite a while.

My mother spent several weeks in hospital and when she came home she was bedridden for a long time: there were complications with her leg, which had to be broken again and reset, so she was obviously in no condition to do anything much. Luckily for all of them, I was young, fit and strong, and I tackled everything that needed doing. Not, I might add, without help from some of the older children. We cleaned house, washed, ironed, cooked, took care of Mummy and also somehow managed to get ourselves off to school and college and do the required homework and studying.

Therefore, when I finished my last exam I did not go to work at the Golden City Post because taking care of my mother and the rest of the family was, at that point, more important than anything else in my life.

However, the people at the newspaper had not forgotten about me … about ten days after the college closed for the year, I received a telegram at home (we had moved from the flat in Ophirton and were living in a house in 15th Street, Fietas, opposite the mosque on the corner of Krause Street). The official name of the suburb was Vrededorp, but most people I knew referred to it as Fietas. We did not have a telephone, hence the telegram. It said something to the effect that Cecil Eprile was waiting to see me and I should come in to his office or phone pronto.

That evening when Daddy came home, there was a heated discussion about me going to work for this ‘native’ paper and that I was a girl for godsake, that how could I go around traipsing after stories at all hours of the day and night and so on and so forth. All my arguing and entreaties went for naught in that first round.

The telegram was followed a few days later by a visit from no less a personage than James Richard Abe Bailey himself. Jim Bailey, as he was commonly known, co-founded Drum in 1951. He later became the sole proprietor and in 1955 launched the Golden City Post, a weekly tabloid newspaper with separate editions for the Cape and Natal. Bailey was a fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force during World War II, and in December 1995 he was named in Queen Elizabeth’s New Year Honours List and made a Commander of the British Empire (CBE). I know that many people detested Bailey for a variety of reasons—mainly his penny-pinching ways—but I quite liked him. I found his quirkiness, sense of humour and the way he related to people from all walks of life quite endearing after I got to know him a bit better.

Bailey was accompanied on his visit to my home by Eprile and his elfin secretary Dolly Hassim. My mother was still confined to bed, but I took my visitors to her room where they had a lively and very matey-matey chat about all and sundry and, more especially, the future of young Juby.

After they left, I made tentative enquiries of my mother and discovered to my great joy that they had convinced her I had the makings of a good reporter and she was now prepared to let me join the staff of Golden City Post. However, we would have to persuade my Daddy to our way of thinking. I did not know it at the time, but I was going to be provided with a powerful lever that would swing things in my favour.

A few days after their visit, I received another telegram from the then Transvaal Education Department informing me of a teaching post in Nelspruit and whether I would please present myself there when school reopened in January 1958.

Daddy had been informed about Bailey and company’s visit and, despite my mother’s attitude that it would be okay for me to work for the newspaper, he was implacably opposed to the idea. After I received the telegram from the Education Department, I cheerfully informed Daddy that I would be off to Nelspruit in January and would look for accommodation on my arrival there, where we knew not a soul in that part of the country.

As I quietly suspected he would be, Daddy was horrified at the very thought of me going off to teach in Nelspruit—or anywhere away from home for that matter. He ranted and raved and cursed the audacity of the department for wanting to send a young girl like his daughter to teach so far from home. As far as he was concerned, the whole lot of them could go to hell—Juby was staying home!

I waited, crouching, until the storm abated, then I sprang into action. ‘Daddy,’ I said in my sweetest, most cajoling voice, ‘I do not intend staying at home doing nothing. You gave me the opportunity of obtaining an education and I am not going to waste it. So either you let me go to work as a reporter or I go to Nelspruit and teach …’

I feared he was going to explode again, and he did. But after stalking about the house, swearing and cursing at all and sundry, waving his arms and smoking cigarettes like there was no tomorrow, he mumbled a few further expletives and said he would talk to my mother. They must have had their talk that evening, because the following morning before he went off to work, my Daddy reluctantly informed me that he and Mummy had decided that it would be better if I became a reporter because at least then I would still be living at home. Victory!

And so it was that on 9 December 1957, about three weeks before my twentieth birthday, I left home early to catch a tram, on my way (and with much trepidation) to my very first job—as a cub reporter for Golden City Post. And the rest, as they say, is history. But I guess I have to tell it, this being by way of an autobiography.

- Juby Mayet, (1937—2019) was born in Fietas, Johannesburg. She began writing at a young age, working first at the Golden City Post, moving to Drum, and joining Voice in 1977. Mayet was a founding member of the Union of Black Journalists and a member of the Writer’s Association of South Africa. She was detained in 1979 and, following that detention, was served with a five-year banning order. Her career spanned five decades, and although not always working as a journalist (she worked as a cleaner and a secretary), she cleared the path for black women journalists, and inspired generations of South African journalists.

~~~

Publisher information

‘Then, it was a big disgrace—skandaal!—for a young girl to get herself pregnant outside of marriage. I was already a very focal point of community gossip: I was doing something no Malay girl had ever done before me […] I was a reporter on a “naytiff” paper, and I was seen all over the place in the company of “naytiffs”—eating with them, walking and talking with them, partying with them and jislaai! coming home with them in open-top Cadillacs!’

The late, great Juby Mayet passed away in April 2019 at the age of 82. The New Age. Drum, Golden City Post, Voice—some of the greatest publications of an era—were elevated by Juby’s voice. Her hepcat, jazz-inflected writing is thrilling, and all the more so in this, her memoir. Mayet was a writer and a fighter, for whom media freedom was sacred, and being a writer was the greatest thing a person could do.

Susanne M Klausen’s afterword is an essential and elegant contribution to Juby’s life and times, and an urgent call for Juby Mayet to receive the recognition she so deserves.