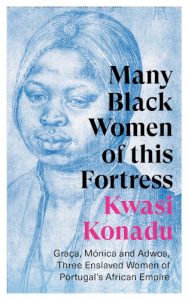

The JRB presents an excerpt from Many Black Women of this Fortress: Graça, Mónica and Adwoa, Three Enslaved Women of Portugal’s African Empire by Kwasi Konadu.

Many Black Women of this Fortress: Graça, Mónica and Adwoa, Three Enslaved Women of Portugal’s African Empire

Kwasi Konadu

Hurst Publishers, 2022

Read the excerpt

Documentary evidence for the lives of African women and girls is exceedingly rare for the sixteenth century and even scarcer for the fifteenth century. Almost all African women and girls whom Portuguese mariners encountered in those years were rendered nameless in their accounts. Men from Portugal were the first early-modern Europeans to arrive on the West African coast, and their global empire, built with African gold and bodies, left a large but incomplete paper trail. An earthquake in 1755 destroyed most of the royal archives and of Lisbon, obliterating what we could potentially know. Newly discovered records for Graça’s homeland, however, offer exceptions to the paucity of documented lives. Graça was born between 1470 and 1480, though she entered the strangers’ chronicles decades later. In the 1490s, the Mina (Gold) Coast featured African female merchants like Briolanja, among other women mentioned by name or in passing or inscribed as enslaved persons. The same records reveal that Portuguese women were also merchants but working in tandem with male slave traders. Isabel Machada and Beatriz Esteves were paid to care for captives procured by male merchants, usually on the basis of shared costs, but these women also purchased captives under their care. Carer and slaveholder Marta Fernandes paid ‘for a very young little slave who was given to her to be treated at shared cost.’ Most white women residing at the main Portuguese fortress on the Mina (Gold) Coast, then called São Jorge da Mina (now Elmina Castle), were exiled and not necessarily unmarried, and a few fortress captains did bring their wives with them. White women were usually few in number compared with the large roster of enslaved African girls and women, like Graça and Mónica, divided as they were among male residents and officials of the fortress. Some of these bonded women and girls hailed from greater West Africa, while others were Africans or women of African descent from Portugal. In the mid-sixteenth century, two manumitted women of African descent came from Lisbon and worked in the fortress’s oven-house and infirmary. These women held estates worth up to 60,000 réis, but since the manumitted and enslaved did the same menial work in Lisbon and throughout the empire, they were rare anomalies in sharp contrast to the widely shared experiences of women like Graça, Mónica, and Adwoa.

There are very few studies or life stories of African women before the nineteenth century, and recent scholarship on African women starting in the late seventeenth century remains focused on how they made use of their relations with European (and mixed-race) men and the opportunities offered by them. In other words, those men constituted an integral axis around which these women gained status, accrued property, experienced mobility, wielded nominal authority, or succumbed to sexual and other acts of violence. It is also widely assumed that African women and women of African descent in Atlantic Africa even in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries owned property, wielded influence, and exercised some power on account of their reliance on European (and mixed-race) men. Surely this is an important aspect of complex intercultural and intercontinental relations, though relatively few African women occupied those indeterminate or intermediary roles. This book, Many Black Women of this Fortress, takes a different view, arguing that there were more often ordinary African women and girls who did not submit to empire and their male European agents. Instead, they stood up for themselves and exercised spiritual and female powers independent of European and African men in an age of maritime, slaving, and missionary empires.

In the formative era of European global empires, pioneered by Portugal, we know the least about the number of enslaved and freed African women subjected to both Portuguese commerce and religion, and even less about their lived experiences, especially in large parts of the African mainland where miscegenation was rare. Though the Portuguese monarchy’s prohibition of unions between Portuguese men and African women had mixed results, it would seem that for the women of Graça’s, Mónica’s, and Adwoa’s world in Atlantic Africa, miscegenation was uncommon apart from on the islands of São Tomé and Cape Verde. Their experiences run counter to popular notions. And those lived experiences came face to face with a global empire and its terror-inducing institutions such as the Inquisition. The intertwined lives of African women like Graça and Mónica who served in the premier colonial outpost of the Portuguese empire in West Africa provide another narrative for stories of freedom and nonviolent Atlantic exchanges; indeed, their insurgent spiritual ideas and actions defy the all-too-common plotline of movement from slavery to freedom. Graça and Mónica relied far less on their connections with the ‘Atlantic world’ for their status and power, instead activating their own forms of ‘female power’. While the archival sources are rare, the experiences of these women cohere with those of dozens of other women in the same period and same places, making them windows into a collective history.

Among the young and old, enslaved and manumitted, unconvinced and baptised African women and girls of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were many who defied the global empire. While some liaised with European men along the African coast, these ordinary yet bold women pushed back against new forms of captivity, racial capitalism, religious orthodoxy, and sexual violence, as if they were self-governing. Looking at those formative features of modernity through the lives of these women, we can see the world fashioned by empires as a space at war over beliefs, precious metals, commodified bodies, and goods. Our guides to this evolving world are three African women—Graça the elderly captive, Mónica the manumitted spiritualist, and Adwoa the eyewitness to the failure of religious conversion and Portuguese colonisation. Many Black Women of this Fortress reveals the insurgent ideas and actions of these women, which is to say the exaltation of their cultural norms and forms, as well as their spiritual bearings, nurtured on local African soil. Theirs is a narrative, or set of stories, written from obscurity, from the forgotten and overlooked records of empire. By drawing attention to these lives, we dare to approximate the complexities of what happened, offering close-ups of modernity’s gestation. These women invite us to consider anew the world shaped by global empire and racialised capitalism in the crucial fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

- Kwasi Konadu is John D and Catherine T MacArthur Endowed Chair and Professor at Colgate University, teaching worldwide African histories and cultures. He is the author of Our Own Way in This Part of the World: Biography of an African Community, Culture, and Nation; and co-editor of The Ghana Reader.

~~~

Publisher information

A haunting triple biography of women whose lives were indelibly shaped by slavery, race and the Inquisition.

This book presents rare evidence about the lives of three African women in the sixteenth century—the very period from which we can trace the origins of global empires, slavery, capitalism, modern religious dogma and anti-Black violence. These features of today’s world took shape as Portugal built a global empire on African gold and bodies. Forced labour was essential to the world economy of the Atlantic basin, and afflicted many African women and girls who were enslaved and manumitted, baptised and unconvinced.

While some women liaised with European and mixed-race men along the West African coast, others, ordinary yet bold, pushed back against new forms of captivity, racial capitalism, religious orthodoxy and sexual violence, as if they were already self-governing. Many Black Women of this Fortress lays bare the insurgent ideas and actions of Graça, Mónica and Adwoa, charting how they advocated for themselves and exercised spiritual and female power. Theirs is a collective story, written from obscurity; from the forgotten and overlooked colonial records. By drawing attention to their lives, we dare to grasp the complexities of modernity’s gestation.

‘This remarkable book recovers from the Portuguese archives the life histories of three women who lived in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in present-day Ghana. Konadu, an outstanding historian of his generation, presents a lucid, riveting and transformative portrait of gender and politics in the face of the violence of European empires at the dawn of modernity.’—Toby Green, Professor of Precolonial and Lusophone African History and Culture, King’s College London

‘A fascinating picture of the entangled early modern world. Using the rich archival material found in inquisition records, this book provides an important new window onto the daily lives of three Black women in sixteenth-century coastal West Africa, and in Europe.’—Bronwen Everill, Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge

‘A refreshing, remarkable excavation of the kind of life stories typically lost to history. Methodologically creative and bold in reach, this is a book that forces us to rethink both what we know and what we are able to know.’—Paddy Docherty, author of Blood and Bronze